Do we need another Lucian Freud exhibition? After years of exposure to his paintings of naked bodies posed like casualties of a car crash in a nudist camp, we might have reached the ‘move along, nothing to see here’ point. But it seems we can’t get enough of the monstre sacré. To mark the centenary of his birth in 1922, London is being treated to a Freud fest of no fewer than seven exhibitions, the most prestigious of which is at the National Gallery.

Subtitled New Perspectives, the National’s show promises a change of viewpoint from the perspective now most commonly associated with Freud (that of looking down on figures sprawled or splayed across beds or sofas), a promise initially fulfilled in the opening room of rarely seen early works painted under the influence of Cedric Morris. From the sulky teenage ‘Self-portrait’ (1940) to the wide-eyed ‘Woman with a Tulip’ (1945), the young Freud approached his human subjects head-on with a level, sharply penetrating gaze.

But what might have been formative works became dead ends when, in the mid-1950s, he underwent a complete change of artistic personality. Two things happened: he took to standing at the easel dominating his subject and – under the influence of Francis Bacon – he exchanged the razor-sharp focus of his youthful paintings for loose, expressive brushstrokes emphasising the physicality of flesh.

In the British monarch the artist met his match: a female subject he was unable to look down on

Freud’s new looser handling didn’t soften the hawk-eyed gaze that caught his early female subjects like rabbits in the headlights. Determined to paint things ‘that are not made up’, he directed the same ruthless observation at everything – flesh, floorboards, furniture, houseplants, piles of paint rags – in his line of vision, including his children.

There’s nothing intimate about the treatment of the children in the section of the show called ‘Portraying Intimacy’: the giggles in ‘Naked Child Laughing’ (1963) and ‘Reflection with Two Children’ (1965) betray their embarrassment, and the defensive pose of the half-naked child with a hand between her bare thighs in ‘Large Interior Paddington’ (1968-69) verges on pervy. The potted linden tree the little girl is curled up under seems to have more sympathy than her father with her vulnerability.

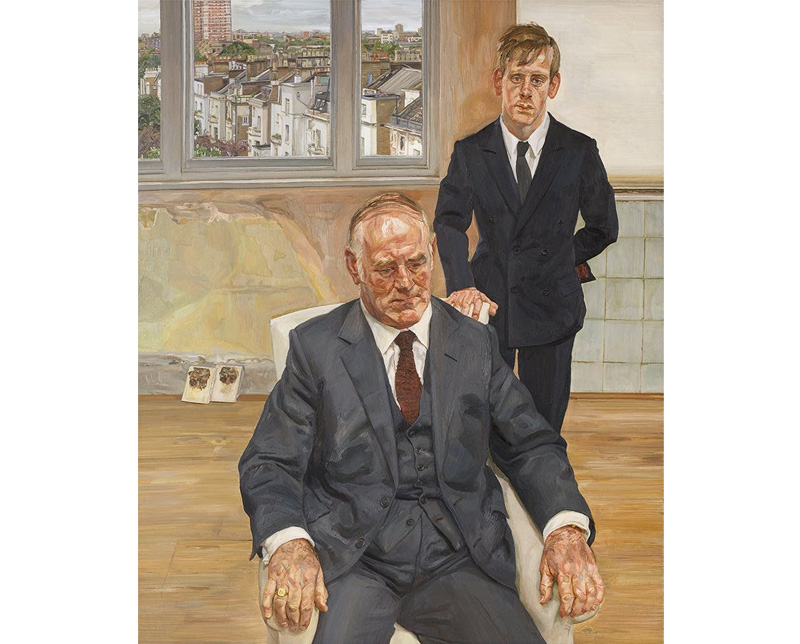

Freud’s subjects often look more like victims than sitters, but some survive with their composures intact. The ‘Two Irishmen in W11’ (1984-85) bring a breath of fresh beery air into the turpsy atmosphere of the studio: no mere artist is going to outstare these local hard men. Among the subjects of ‘naked portraits’, Sue Tilley and Leigh Bowery preserve their dignities under coverings of fat, unlike the thin, foreshortened ‘Naked Girl’ (1966), as exposed as a patient on a gynaecologist’s table. But the great survivor of Freud’s merciless gaze was ‘Her Majesty The Queen’ (2000-1). In the British monarch the artist met his match: a female subject he was unable to look down on.

The other woman he couldn’t subdue was his mother, Lucie. As her favourite child he had always felt smothered by his mother, but her depression after the death of his father, Ernst, in 1970 – and her subsequent indifference to him – freed him to paint her. From a thousand sittings spread over 15 years emerged the most intimate portraits Freud ever produced. The show features a handful of touching drawings including ‘The Painter’s Mother, Dead’ (1989) – though not, sadly, the 1973 painting in the Tate that deserves a place in the pantheon of artists’ mothers alongside Dürer’s, Rembrandt’s and Whistler’s.

The other most sympathetic portraits in the show are of dogs, although the sidelong look in the terrier’s eyes in ‘Guy and Speck’ (1980-81) suggests a wariness even on his part. Freud loved animals; he also loved plants. The most positive image in the show is of ‘Buttercups’ (1968) in a sink. Flowers didn’t wilt under his gaze: they held it and he rewarded them with respect. The tulip upstages the woman in ‘Woman with Tulip’, and the yucca plant and linden tree in the studio paintings are given equal billing with the people.

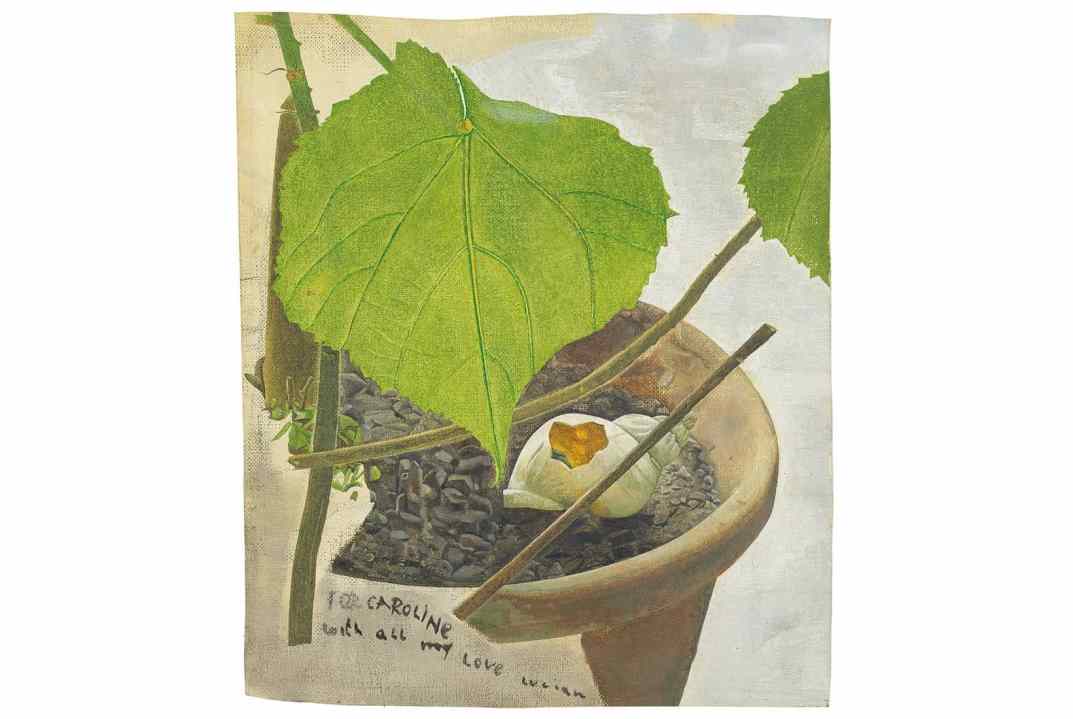

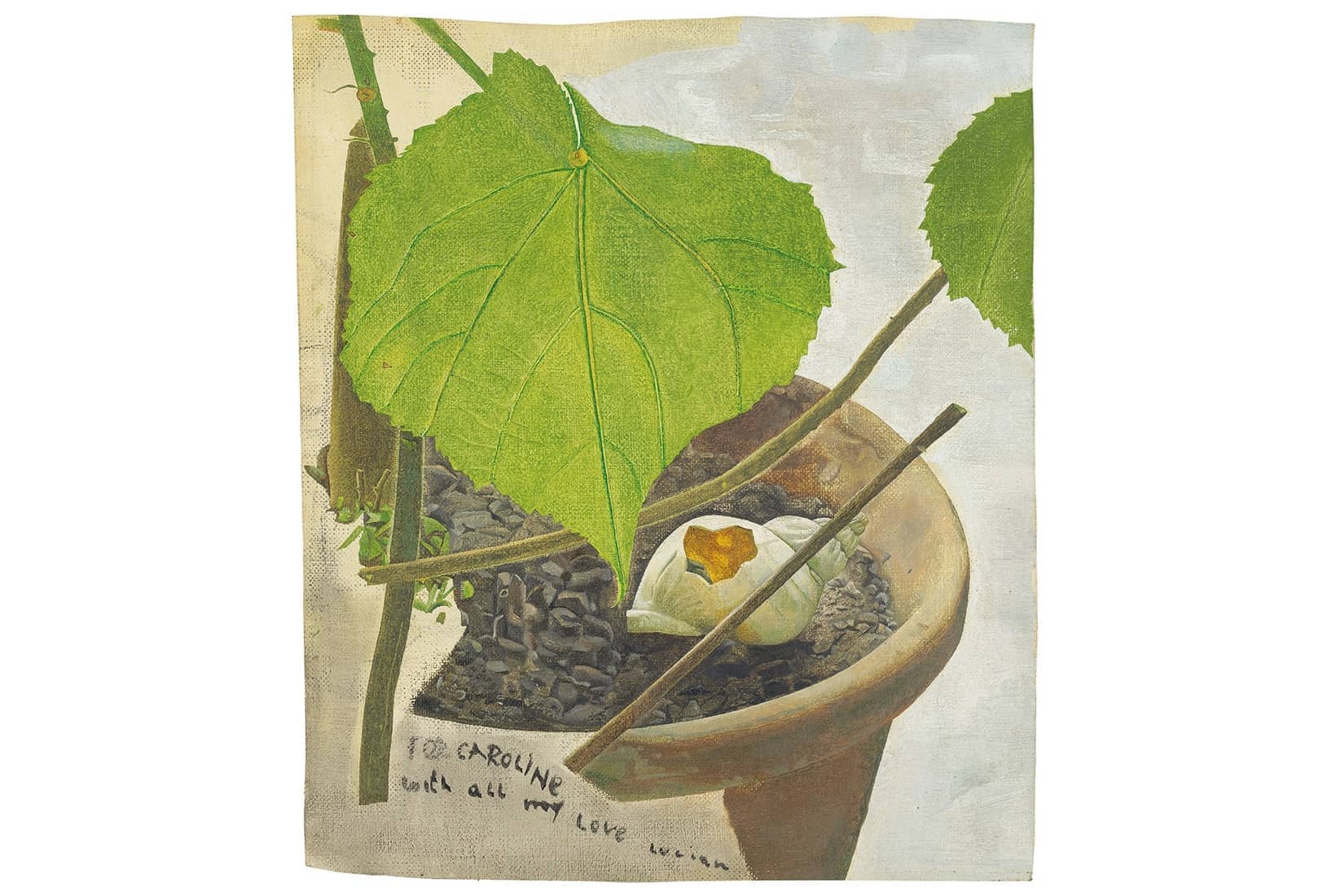

For a genuinely new perspective on Freud, visit the Garden Museum’s exhibition of Plant Portraits. The hands of ‘Bananas’ (1953) he studied in Jamaica; the ‘Unripe Tangerine’ (1946) he picked in Greece; the ‘Gorse Sprig’ (1944) he scrutinised in Sussex, with new buds and dead needles on the same stem: all are portrayed as distinct characters shaped by their individual experiences of life. The influence of Dürer’s ‘Large Piece of Turf’, of which a print hung in the family flat in Berlin, is visible in a 1993 etching of daisies and plantain sprouting on a patch of turf lovingly brought back from Tuscany. The lusciously painted hollyhock and foxglove in ‘Flowers on a Red Chair’ (1998) are not sprawled or splayed across the seat, but delicately placed. If he hadn’t succumbed to the pleasures of painted flesh, Freud might be remembered as a very different artist.

Comments