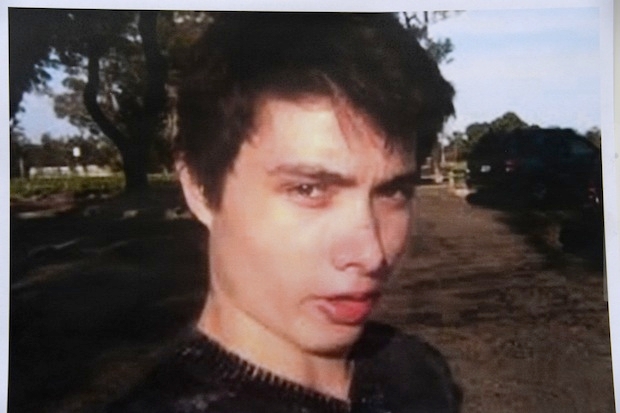

I’ve found myself strangely drawn to the videos made by the 22-year-old assassin Elliot Rodger just before he went on his killing spree in his university town of Santa Barbara, California, last week. In a series of stabbings and drive-by shootings Rodger killed seven people, including finally himself, and wounded 13 more. The son of a film director, he had spent the first few years of his life in England, moving to America at the age of four.

Rodger had been preparing for his murderous spree and made a series of videos, many of which are accessible on the internet as I write. The last was recorded by himself the day before his attack. He sits parked in his car, arranged so that the sun, low in the sky, spotlights his face in an orange glow.

The video is about six minutes long and shot with a single fixed camera (presumably lodged somewhere in his BMW); the focus is stable and good; and the ‘piece to camera’ appears to have been completed in a single take. His lines are delivered in a relaxed and unhurried manner, with hardly a single um or er, with effective pauses for dramatic effect, with theatrical chuckles thrown in, and without the frozen or ‘rabbit-in-the-headlights’ impression which usually afflicts amateurs. He sometimes moves in a little closer to the camera, to emphasise a point. He never stumbles and. apart from repetition and the misuse of the word ‘tortuous’ (he means ‘tortured’), it’s a pretty decent little video essay. Rodger is the kind of speaker to camera whom producers call a ‘one-take wonder’. He’s better than I am at it.

But that’s to ignore its content, which in the light of what was to occur on the following day — in the light, that is, of our ex-post-facto discovery that Rodger really meant it — the video is obscene. In it, he repeatedly blames the world, women, and blond women in particular, for his loneliness; he tells us that he’s still a virgin at 22, that he cannot understand why no women want to love or sleep with him, and that he’s going to exact his retribution by killing them.

While watching this and another roadside video Rodger made, I could not banish from my mind a comparison with another American mass murderer, Timothy McVeigh, who in 1995 killed 168 people with a bomb in Oklahoma City. McVeigh was a right-wing hater of government, which he wished to punish. Before his execution, he chose William Ernest Henley’s poem ‘Invictus’ (‘I am the master of my ship, I am the captain of my soul’) as his final statement.

I watched an interview with McVeigh after the atrocity. He was asked what he now thought about it at the time. His reply was quite extraordinary. ‘I think, like everyone else, I thought it was a tragic event,’ he said.

Both these men, Timothy McVeigh and Elliot Rodger, seem to have seen themselves as starring in their own movies. Their lives had turned into out-of-body experiences.

Rodger, as it happened, seems to have had some experience of making a film, and made his own quite professionally. McVeigh let others make the film: he just directed, script-wrote and starred. McVeigh chose a poem for the final credits; both men — you can tell — would have been comfortable with a motion picture musical soundtrack for their interviews and for their act of violence itself. Both spoke almost movingly (if it is possible for a man who takes the lives of others to attract sympathy for his own) about youth, isolation and loneliness. Both are anxious to impose upon events a narrative with a back-story: a plot, almost.

Is there something about 21st-century American culture which causes Americans to think — on some weird, subterranean level — that their own lives are films in which they are playing the central role? I ask because I do think there are very big differences between the way we British and the rest of Europe — the ‘Old World’ — see life, and the way Americans seem to. I realise that in saying so I have suddenly jumped from two obvious psychopaths, which any society can produce, to an entire nation, and this may seem unwarranted; but there are some recurring patterns in the way Americans, when they go crazy, choose to go crazy. They seem to choose a big screen, a big event, a manufactured theatricality, incredible violence — and always, always, guns. Often, too, there will be a chase. Usually there are automobiles involved.

As a British occasional watcher of American movies and TV series, I have become sick of the near inevitability of extreme violence, extended gun battles, and careering motorcars. It is almost as though such episodes have become part of the form a movie takes. Greek tragedy requires the unities of place, time and action. A Hollywood blockbuster requires gunfights, gratuitous violence and fast driving. And a kind of glory, too. Glory breathes through Rodger’s video.

I wonder if continual exposure to such cinematic fantasy has conditioned a national culture in which a really good story calls for these elements: and in which, if a man’s own personal story runs out of road, he will choose a denouement in which many die violently, and he himself dies either as part of the action, or after dramatic courtroom scenes lead to his (violent) execution.

We British tend quietly to take a lot of pills, or throw ourselves under trains. And of course most American suicides are of this nature too. But the regularity with which these awful stories do emerge, where an American death has been organised as a film director would organise it — and the rarity of such orgies of destruction in our own country — invites a question about our comparative national cultures.

It invites a question, too, about a civilisation in which so much of an individual’s own life story is spent watching fictional accounts of other people’s life stories that individuals begin to live on a meta-level — as it were — where they become the audience for a movie about themselves.

No doubt I over-interpret. But watch Rodger’s video, and ask yourself how likely it would be that a British boy would even dream of doing it like that. Perhaps if Elliot had been raised here rather than born here he might have departed with a whimper, rather than that awful, vainglorious bang.

Comments