Coronavirus has cast a dampener over this year’s Mayflower 400 celebrations due to a hidden enemy with which the Pilgrim Fathers were all too familiar: within months of their arrival in America more than half of them had died of a disease whose principal symptom was violent coughing.

There was no official artist on the Mayflower. Its ragtag party of Separatist Puritans had only been granted a charter on condition that their religious affiliation, banned in England, was not formally recognised. So we can only imagine how the New World looked to the cabin-feverish colonists who made landfall at Plymouth in December 1620, lustily shaking ‘the desert’s gloom/With their hymns of lofty cheer’, if you believe Felicia Hemans’s patriotic poem — or coughing their guts up.

There had been an artist on Sir Ralph Lane’s earlier expedition of 1585, the first attempt to found an English colony in North America, on Roanoke Island off what is now North Carolina. John White was commissioned as mapmaker and illustrator to this expedition, and promoted two years later by Sir Walter Raleigh to the position of governor of Roanoke and any future ‘Cities of Raleigh’. But White was better at painting than governing. His Portuguese navigator, known as ‘the swine’, stopped obeying orders; he attacked the wrong Indians — ‘we were deceaved, for the savages were our friendes’; and he was eventually obliged to leave his daughter and new granddaughter Virginia, the first English baby born on American soil, on Roanoke while he returned to England for supplies. When he finally made it back in 1590, on his granddaughter’s third birthday, he found the settlement deserted.

The ‘Lost Colony’ was never found, and White returned to England a broken man convinced he had been born under ‘an unlucky star’. But one man’s evil star is another man’s lucky one. In London his illustrations of Algonquian life had come to the attention of the artist Theodore de Bry, a Calvinist refugee from Catholic Flanders. A goldsmith by trade but an entrepreneur by instinct, at the age of 60 De Bry was moving into copper engraving and in White’s pictures of American Indians he smelt money.

A wooden butt plug was inserted into a victim’s rear prior to cooking ‘so that nothing escapes out of him’

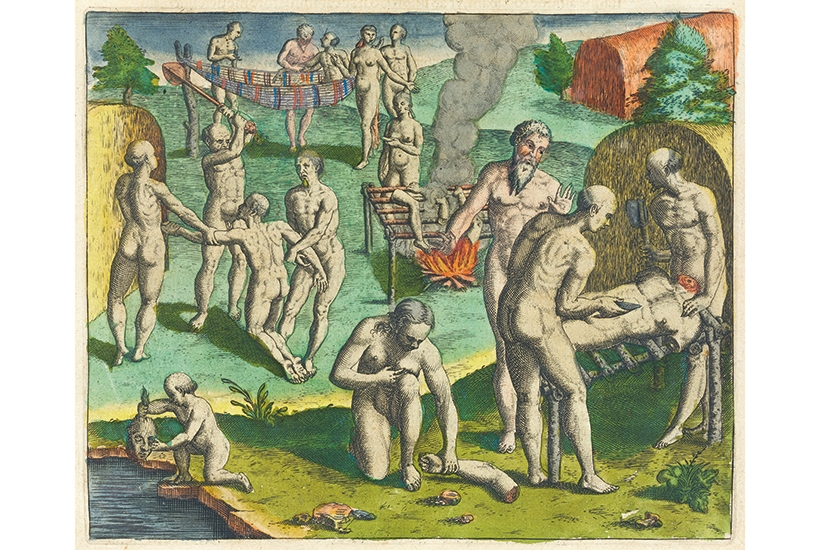

Tales of Christian explorers’ encounters with heathen savages were attracting an enthusiastic readership in Europe, but none had so far been illustrated with any but the most basic woodcuts. De Bry’s wheeze was to reissue these proven bestsellers in large-format luxury illustrated editions: the original coffee-table travel books, liberally spiced with non-gratuitous native nudity, gratuitous violence — European and Indian — and visions of mineral riches beyond the dreams of greed.

Having acquired the rights to White’s watercolour drawings in London, De Bry moved to Europe’s book capital, Frankfurt, where in 1590 he brought out the first volume of a planned series on the Americas, illustrating Thomas Harriot’s A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia with engravings based on White’s watercolours. For Volume II he matched the watercolour drawings of another Protestant refugee he had met in London, Jacques Le Moyne, with a written account by René Laudonnière, both survivors of a failed French attempt to plant a Huguenot colony in Spanish Florida in 1564.

Following Volume II the books kept coming, always in time for the Frankfurt book fair. Between 1590 and 1634 the family business De Bry founded with his sons would bring out 13 volumes in the America series, the first nine of which have just been reissued by Taschen in one sumptuous doorstop of a tome combining plates from the finest hand-coloured editions.

The De Brys felt no compunction about ‘improving’ White’s and Le Moyne’s originals in their engravings, and took greater artistic licence as the series wore on. They had not crossed the Atlantic, but neither had their readers. The type of Amerindian they developed, with athletic muscle definition and classical proportions, was quite unrelated to the native physiques in White’s watercolours now in the collection of the British Museum. In fact, their Indians bore about as much resemblance to flesh-and-blood humanity as the cartoon figures in Marvel comics, with whose plotlines — involving alien civilisations, mythical beasts, semi-clad women and male crusaders for Christian justice wearing capes and tights — their stories had much in common.

That said, the book is full of wonder for the Indian way of life, for their ingenuity (the ‘cunning way’ they fish, their ‘fine’ earthenware that ‘our potters can make none better’, the ‘most wonderful’ way they make their boats), their attire (the women are ‘beautifully dressed’), their singing (‘their voices and harmonies went together so delightfully’), their moderation in eating (‘I wish we might follow their example’), even their moral rectitude in always sharing crops and never fighting over food (‘it would be nice if such a lack of avarice prevailed among Christians’). There’s amazement too at their way of hunting deer, ‘completely new to us’, whereby Indians, robed in deerskin, using a stag’s head as a mask, would spy on their prey pretending to be one of them. It’s a jolt after all this to see the Indians referred to as ‘savages’ and ‘brute beasts’.

Strangely, the more hair-raising practices are depicted without judgement. Perhaps they felt it wasn’t necessary. The passages on child-sacrifice are all the more shocking for being so matter of fact. Cannibalism loomed large, especially in Volume III’s account of Hans Staden, a German gunner in the service of Portugal who ‘decided I would go and see the Indians’ and ended up almost literally in the soup. The story of his capture and imprisonment by the cannibalistic Tupinamba tribe in Brazil goes into graphic detail — TMI — about the wooden butt plug inserted into a victim’s rear prior to cooking ‘so that nothing escapes out of him’, and is illustrated with gruesome images of human body parts laid out on a grill. ‘I witnessed this myself,’ Staden insists. We’re not told how he lived to tell the tale.

The illustrations to America — though fascinating — were not great art, but so great was the success of the series and so wide its distribution that they left a permanent imprint not only on European perceptions of the New World but on the iconography of European art. There are echoes of their Floridian youths at their exercises in Degas’s ‘Young Spartans’; of their Inca women bathing in Atahualpa’s camp — unaware that they’re about to be raped by Pizarro’s soldiers — in Cézanne’s ‘Grandes Baigneuses’; and, more astonishingly, of their trio of Secotan women performing dances at feasts in Canova’s ‘Three Graces’.

An even less adulterated picture of the indigenous cultures of the New World has come down to us in the contemporary Histoire Naturelle des Indes known as the Drake Manuscript. Dating from the early 1590s, this handwritten and illustrated account of West Indian flora, fauna and native life was in private ownership until 1983 but is now in the collection of the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, and online. Although Sir Francis Drake is known to have dabbled, the watercolours are by several hands none of which can be confirmed as his, but the text, which names nearly 30 of his ports of call, could be by a French Huguenot who travelled with him.

The picture its author paints presents Caribbean society as a highly developed alternative culture. He is full of praise for the Indians’ many skills, in weaving ‘beautiful cloth of fine wool’, modelling animals in gold relief, fashioning fishing nets and hammocks, baking ‘very good and nourishing bread’ and ingeniously trapping parrots for export. True, his reliability is thrown into doubt by the curly horns on his ‘moutons du Perou’ — the De Brys got their llamas right — and he skates rather too quickly over cannibalism. But his admiration for the Indians — much like in the De Bry — is boundless: ‘They are so skilled that one could not show them any work which they could not do.’

The actual ‘savages’, of both the De Bry and the Drake Manuscript, were the Spanish. Volume V of De Bry opens on the island of Santo Domingo with plates showing the Spaniards whipping slaves, then pouring boiling tar into their wounds, burying them alive, hacking them to death. These are among the earliest critical depictions of the barbarity of slavery. You might have thought that such images would have jerked our collective conscience, stopped other countries from following suit. But we all know what happened next.

Comments