Before the revolución of 1959, Havana was, effectively, a mafia fleshpot and colony of Las Vegas.

Before the revolución of 1959, Havana was, effectively, a mafia fleshpot and colony of Las Vegas. Graham Greene first visited in 1954, when the dancing girls wore spangled headdresses. The Batista regime was then at its height, and tourists flocked to the Cuban capital for its promise of tropical oblivion.

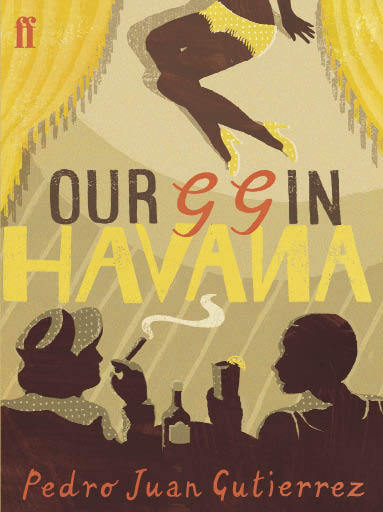

George Greene, the ‘GG’ of the title of this novella, is an English holidaymaker on the prowl in pre-communist Havana. Castro’s revolution is less than four years away — it is the summer of 1955 — and George hurls himself promiscuously into Batista’s grimy sex industry. Teenaged prostitutes hover outside his hotel and their pimps are not much older. Unsurprisingly, Havana will prove his undoing.

Having paid for sex with a Cuban she-male (‘Warm up the engine gently, mister. It’s best to go slowly’), he befriends a local porn artiste called Superman, who is a liability. Along with Superman, George finds himself accused of complicity in the murder of a German businessman, Thomas Gerhardt, who may or may not be a Nazi sympathiser.

Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana is a model for the plot, which revolves round a cast of CIA operatives, Chinese dwarves and a tally of ever-more grisly murders. The Cuban police, meanwhile, are convinced that George Greene is in reality the novelist Graham Greene, and so the author of Brighton Rock also stands accused of murder. In an attempt to clear his name, Greene flies to Havana courtesy of his London publishers, only to flounder in an underworld of anti-Batista revolutionaries, American double-agents and neo-Nazis.

Himself a Cuban, Pedro Juan Gutiérrez evokes the salt-eaten arcades and collapsing promenades of Havana in consciously street-savvy prose and Greenian dialogue. (‘Philosophy in novels is like bitter in cocktails. Two drops. Three is too many.’) Oddly, however, Our Man in Havana was originally set in the Estonian capital of Tallinn, which Greene visited in 1934 on the recommendation of H. G. Wells’s mistress, Baroness Budberg. Gutiérrez’s novella, an amusingly lewd slice of Cuban exotica, is a must for all fans of Greene and Greeniana, but be warned: strong content.

Ian Thomson’s The Dead Yard: A Story of Modern Jamaica is out in paperback with Faber.

Comments