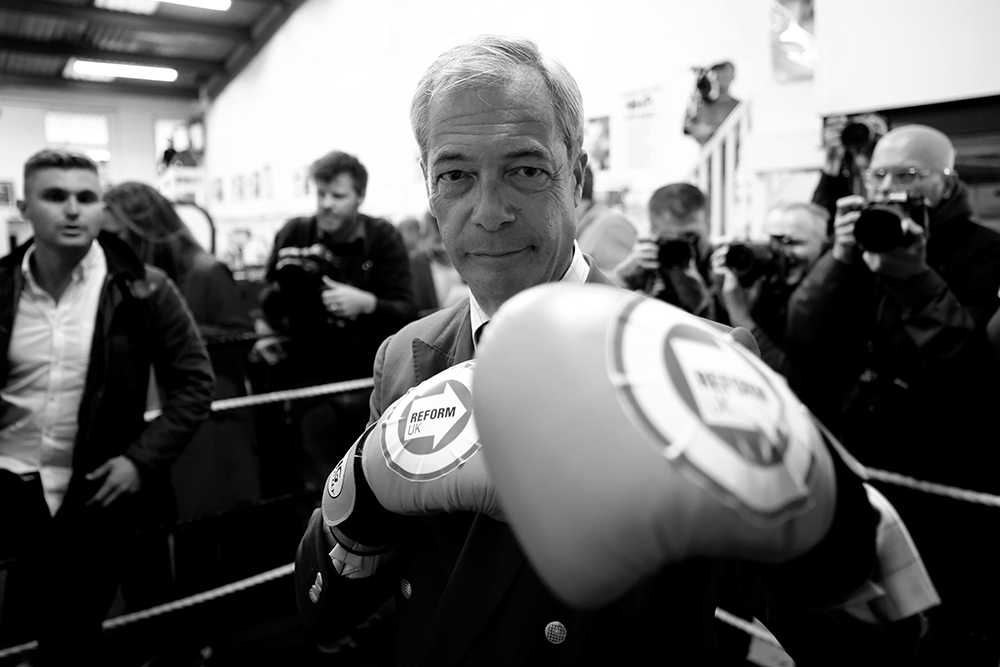

For the past year, Nigel Farage has served as the great pacesetter of British politics. Reform UK has shot to the top of the polls, as Labour and the Tories languish behind. On immigration, the economy and much else, it is his five-man band that sets the tune. It is the inverse of Norman Lamont’s jibe about ‘being in office but not in power’.

From his new base near the top of Millbank Tower, Farage enjoys a commanding view of Westminster. The office, an explosion of teal decor, has a large press briefing room, which aides liken to the one in the White House. At a desk adorned with a porcelain Union Jack bulldog, Farage plots his next steps.

He sees his role as ‘a little bit more [like] the general – not in the front lines so much, but a little bit behind the lines, sort of trying to take some strategic oversight as to what the rest of the party’s doing’. Election planning is to be handled by former Ukip leader Paul Nuttall, the party’s new vice chairman. A six-week summer offensive will begin on 21 July.

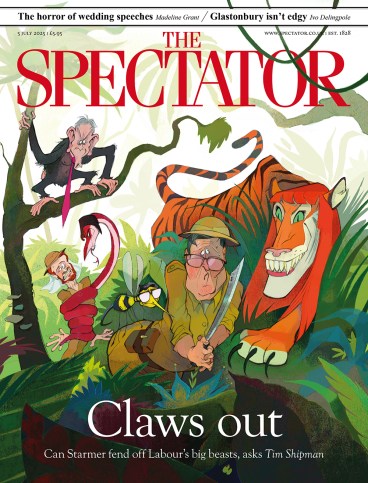

Such machinations matter because of their impact on the government. Keir Starmer says publicly that the next general election will be fought between his party and Reform. Under his chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, Labour is trying to pitch itself to patriotic, immigration-sceptic ‘hero voters’. Yet many on Starmer’s benches want him to switch to a more soft-left approach.

Farage, who has never met McSweeney, says that ‘probably politically, what he’s advocating is right – but the Labour party can’t swallow it’. He cites a surge in support for the Greens, arguing that there is a ‘drag to the left that is going on in British politics’ which only pulls ‘the kind of undecideds on the Labour benches in one direction’.

Reform’s success often confounds opponents who try to place the party on a traditional left-right axis. Yet some within Reform think of it more like a business, hungry for market share, wherever available. Rather than ponder deep philosophical questions, or muse about how to interpret its political heritage, Reform pivots from lifting the two-child benefit cap one month to introducing a ‘Britannia card’ for the super-rich the next.

Farage’s new base has a large press briefing room, which aides liken to the one in the White House

Farage himself prefers to talk in post-ideological terms: ‘I would like to think that people would look at me and look at us and say we’re realistic and pragmatic. I think the benefits stuff that we said surprised a few people, but, you know, we’re not finished on that. There’s a lot more to come out on that agenda over time.’

The debate in April over nationalising steel exemplified this approach. While the shadow cabinet were split over questions about state interventionism, Reform simply pledged nationalisation. For long-established political parties, history can be a bulwark, but it also brings baggage.

Like any general, Farage likes having a free hand to respond to events nimbly. Critics jibe that this leaves Reform rudderless, constantly scrambling to board the next bandwagon. Allies argue that, in a world where a social media post by Donald Trump can blow up the markets, there is much merit in this approach.

For them, the fact that much of Reform HQ has little Westminster hinterland beyond Farage is not a weakness but a positive. The staff are ‘quite normal people’, says one aide. Talks around strategy often reference sport, not politics. Wrestling is a shared love in the office and WWE-style razzmatazz has become a hallmark of the party’s election rallies.

Next May’s regional elections represent the ultimate Wrestlemania for Reform. If Reform wins 30 seats in the new 96-strong Senedd, will Plaid Cymru and Labour cut a deal to keep them out? Six new mayoralties are also up for grabs and Reform is after local celebrities in the mould of Hull boxer Luke Campbell to stand as candidates. ‘Essex is a slam dunk,’ says one insider. There have even been talks about the prospect of attracting DUP grandees ahead of the Northern Ireland elections in 2027.

The two main parties, though, will not go down without a fight. Some within Labour are putting their faith in the New Media Unit. This 28-strong, £1.3 million innovation sits in the Cabinet Office. It aims to help McSweeney ‘take back control’ of communications by targeting government messages at millions of voters online. The insights gleaned here could prove crucial to Labour strategists, as they try to reach key voters ahead of the 2029 general election.

Labour’s backbencher revolt over welfare, meanwhile, gave the Tories some reason to cheer this week. Conservative MPs allowed themselves an ‘evening of fun’ with Gyles Brandreth on Tuesday at the Albert pub in Victoria. Rishi Sunak, now a humble backbencher, enlivened things by debating with the compere about which of the many recent Tory chancellors was truly the ‘shortest-serving’.

At CCHQ there were several encouraging signs too. First, Mark McInnes, the former boss of the Scottish Conservatives, was named as the new Tory chief executive. Then longtime donor Lord Bamford, whom some speculated was about to switch to backing Farage, gave Kemi Badenoch £150,000. Both men are indicative of the arms race in personnel on the right of British politics, as the Tories and Reform battle it out for talent and donations.

At present, there are plenty in the world of media and politics happy to keep a foot in both parties’ camps. As the wine flows this summer, there will be much talk about the future of the right. Many Tories hope that Farage has peaked too early. ‘This parliament is a marathon not a sprint,’ says one MP. ‘There are still four years left to go.’

Such comments will not bother Farage, of course. He and his team believe they are exactly where they need to be: leading the pack, on course for both office and power come 2029.

Comments