After Handel introduced Italian opera to London, Georgians and Victorians went to performances to wear their diamonds and meet friends. As Victoria’s reign progressed, opera percolated down, via brass bands, organ grinders, music hall warblers and whistling delivery boys. In 1869, the Leeds impresario Carl Rosa set up ‘a sort of operatic Woolworths’, a touring company putting on shows in cinemas and working men’s clubs

Lilian Baylis was the other great populariser. In 1897, she took over her aunt’s music hall, the Old Vic, and threw herself into social improvement: ‘My people must have the best. God tells me the best is grand opera.’ With 2,000 seats priced between 3d and 3/- , her operas were so popular that they subsidised her Shakespeare plays. Meanwhile, Covent Garden was running a brief, expensive international season with foreign stars singing in whatever language they had learned the role. It must have been hilarious.

Wagner was thought lowbrow –easy for the herd to understand through his use of leitmotifs

High and low coexisted peacefully until 1930, when Philip Snowden, the chancellor of the exchequer, indulged his opera-mad wife by proposing a public subsidy. Cue chauvinism: public money should not be used for ‘boosting the purposes of long-haired foreign artists’. The battle of the brows was joined, high vs. low: opera was ‘not a national passion, like football’.

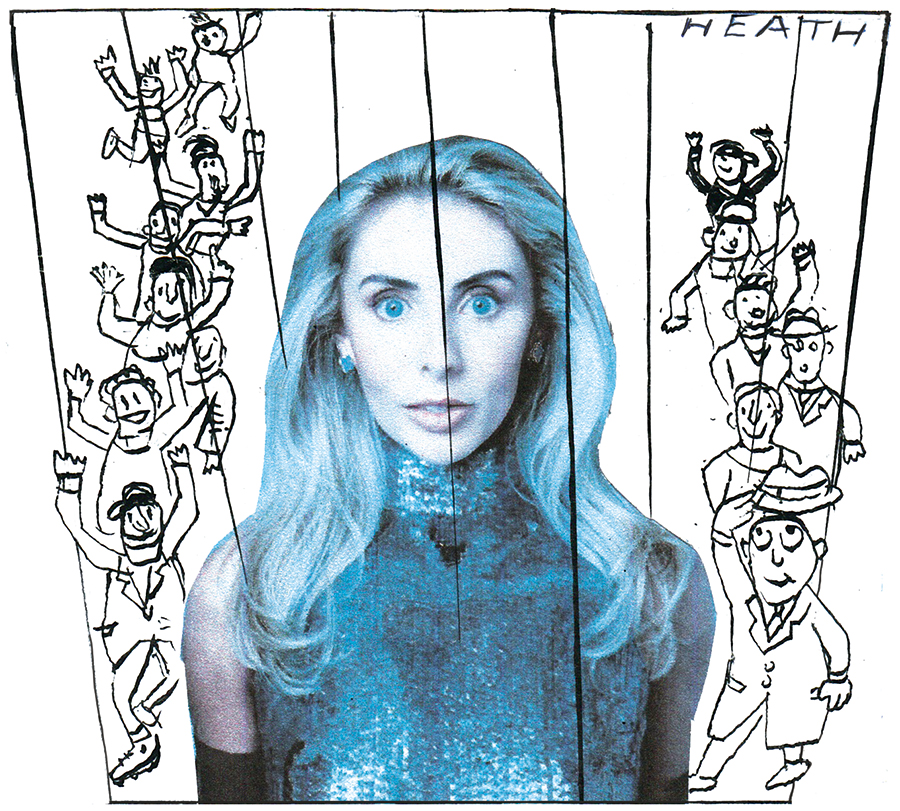

Football vs. opera has been a kickaround political issue ever since. In 1935, a ‘highbrow’ was defined as someone who ‘arches his brows to scorn the philistine herd’. Thomas Beecham’s bushy brows lofted to the skies during his domination of Covent Garden between the wars, bankrolled by his mistress Emerald Cunard. Wagner was considered lowbrow – easy for the herd to understand through his use of leitmotifs signalling characters or ideas. The herd loved Wagner. His bestselling recordings ignited a passion for opera in the six-year-old George Lascelles, later Lord Harewood, who would run or direct the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Opera North and the BBC between 1951 and 1987.

Glyndebourne opened in 1934. John Christie lost money even if every seat was sold. ‘Opera cannot be cheap and good… We have helped many poor people… They cannot perhaps come as often as they like, but nor can they have Van Dycks or Botticellis in their sitting rooms.’ During the second world war, opera went dark. John Lewis, the department store owner, who ran a thriving staff music society, employed Rudolf Bing, the co-founder of Glyndebourne and later general manager of New York’s Met, to manage the hairdressing department of Peter Jones. After the war, Lewis helped Glyndebourne re-open and sponsored an opera competition. The winner, a gloomy-sounding oeuvre concerning a Victorian railway crash, was performed at the opening of the Oxford Street store.

Following the war, antipathy to subsidies subsided. In peacetime, the population turned to the solaces of self-improvement and high culture. ‘Opera is no longer the hobby of millionaires but the delight of millions,’ reported House and Garden in 1950. Two years later, the Football Association organised a competition for ‘the hearty and the highbrow’.

How did we get from there to today’s ‘elitist’ snarl? In Someone Else’s Music, Alexandra Wilson names the 1980s as the time when the meaning of the word ‘elite’ changed from ‘the flower, the best’ to a culture-related insult. The one frustration of this otherwise splendid book is that the author cannot pinpoint the moment more precisely. But maybe there wasn’t a single cause, just a drip-drip-drip as opera elitism gathered pace.

The tide might have been turned. Opera-for-the-people revived in 1990 when Pavarotti employed his mighty voice box to boom out ‘Nessum dorma’ during the Football World Cup. Raymond Gubbay jumped on the bandwagon, staging operas like pop concerts in vast arenas. The opera establishment should have capitalised. Instead, they huffed and puffed at the use of amplification. As the 1990s continued into Tony Blair’s Cool Britannia, nothing was less cool than high art.

The title of Wilson’s book is taken from Oscar Wilde. He glimpsed how vulnerable opera was to the charge of ‘someone else’s music’, belonging to foreigners, aristocrats, longhairs and (shudder) intellectuals, likely to become a political football. Wilson points to anxieties about class, education and national identity as creating the opera-elitism stereotype. She came to opera through school trips and hearing snippets on Inspector Morse. She is now a distinguished academic. Her pain at opera being considered exclusive, even colonialist, and not for the likes of ‘ordinary people’ comes from the heart.

Her faith in the revival of opera as a popular art form is touching. But I don’t see it happening any time soon in Britain, where a cultural life seems almost as shaming as a secret sex kink once was, and few acts are more indefensible than climbing into your best duds, packing a picnic and tootling off to enjoy some unamplified music.

Comments