Almost a century ago, in A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf claimed that if William Shakespeare had had an equally talented sister the obstacles to her sharing his vocation would have been insurmountable. Woolf’s argument that a woman needs ‘money and a room of her own’ in order to write proved persuasive. ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ has become a pop-cultural trope.

So perhaps it’s unsurprising that the distinguished American scholar of the Renaissance Ramie Targoff should borrow the phrase for a study of four woman writers. Her title offers a shortcut to understanding how significant this immensely accomplished quartet is for readers and writers today. Not that Targoff’s elegantly readable, immaculately researched book needs any establishing gimmick. Lucid and detailed, it’s the best kind of literary-historical writing: a page-turner with no trace of lazy fictionalising. And it tells a story of real importance.

Shakespeare’s Sisters examines the life and work of the poets Mary Sidney and Aemilia Lanyer, the playwright Elizabeth Cary and the great diarist Anne Clifford. Alternating chapters juxtapose their lives while retaining a biographical through line. But the book opens with Elizabeth I herself – that centrepetal figure whose patronage, direct or indirect, turned out to be a determining factor in each woman’s life, since, one way or another, all four were born within the orbit of the court.

Earliest, and first to be introduced, is Mary Sidney (1561-1621), the sister of Sir Philip and dedicatee of his long pastoral romance The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia. She first published by editing his work after his death in 1586, and would go on to produce translations and occasional dramas. But perhaps her greatest achievement was her continuation of his project to translate the Psalms of King Davidinto contemporary English verse. Her 107 translations deploy a bravura array of forms. What still astonishes is how she makes English, a notoriously unrhyming language, flexible and singing. Quotable after quotable couplet and stanza transform the parallelism of the original into memorable paradox or deepening thought. Targoff focuses particularly on insights into female experience; but poetic mastery of this order requires no special pleading. Mary’s version was widely admired by Sidney’s literary contemporaries, from John Donne to Ben Jonson.

Aemilia Lanyer (1569-1645) came from more humble origins. Her father, an Italian, possibly Jewish, immigrant, was a court musician. She retained a foothold in aristocratic life after his death, first through a mentorship possibly arranged by one of his patrons, and then as the mistress of the powerful Henry Carey, the nephew of Anne Boleyn. But that hold was tenuous. Once pregnant, she was married off to a court musician and her only son also became a court musician. Later, she was even forced to run a school. Yet she produced two masterpieces, ‘The Description of Cooke-ham’, the first country house poem, and ‘Salve Deus’, a poem sequence of Christian meditations with a uniquely feminist perspective, one of whose dedicatees was Mary Sidney.

A generation younger, Elizabeth Cary (1585-1639) published the first British play by a woman, The Tragedy of Mariam, but marriage at 15 defined her life. As Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, her husband ran up debts which she alienated her own father in trying to pay: he cut her off. After converting to Catholicism, she became part of Queen Henrietta Maria’s Catholic court circle: for this she was briefly imprisoned, abandoned by her husband and left without means of support. The next year, as if unable to avoid trouble, she published her translation of a 494-page French tract against Protestant kingship.

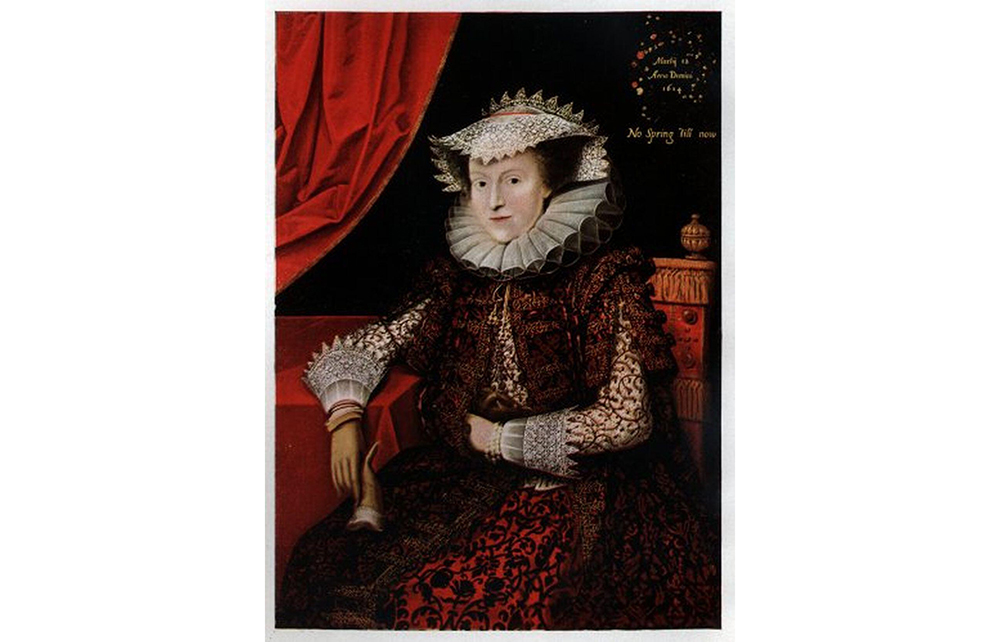

By contrast, Anne Clifford (1590-1676) consolidated the privilege to which she was born. A child favourite of Queen Elizabeth, she inherited a baronetcy at 15, became an important patron and was close to James I’s queen, Anne of Denmark. The letters and diaries she left reveal an exceptional literary intelligence.

Each of this quartet, then, took part in court life at one time or another. Theirs were lives of real privilege, however circumscribed by gender. Only Lanyer’s background comes near to that of the real Shakespeare or his fictional sister; even she was born into the caste of court musicians and players that Shakespeare only eventually joined – and by a route (the professional stage) that no woman could have emulated. None navigated the rough and tumble that later centuries would call the artistic demi-monde, with all it entailed for women’s sexual and social status.

Targoff rightly concludes that the achievements of many Renaissance women writers are outstanding and too often ignored. She claims that her quartet’s successes refute Woolf’s thesis. But whether she means to or not, her illuminating study also reveals that, for the freedom to produce their exceptional work, these women needed – alongside an accidentally exceptional education – unassailable social status and sheer financial force. In Shakespeare’s time, as in Woolf’s, a woman writer did need ‘money and a room of her own’.

Comments