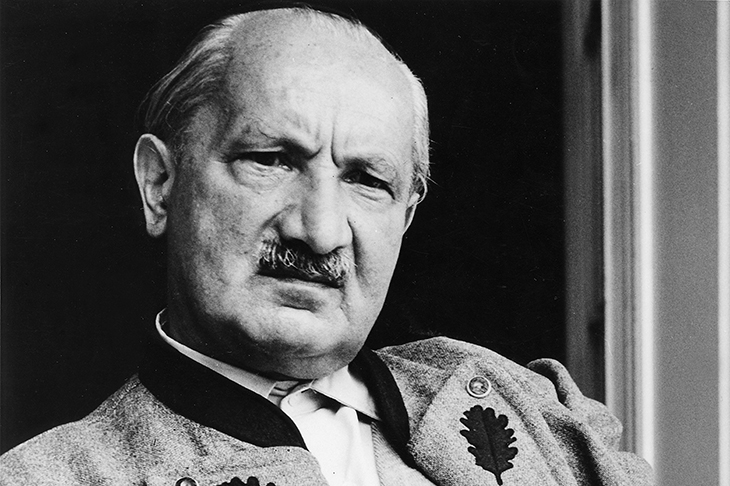

How do you write a group biography of people who never actually formed a group? Such is the challenge Wolfram Eilenberger sets himself in a book about the philosophers Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Walter Benjamin and — the surprisingly unstarry fourth subject — Ernst Cassirer, an urbane and now nearly forgotten neo-Kantian who might have deserved the made-up title of ‘symbologist’, thus far reserved for the heroes of Dan Brown’s novels.

What these men have in common is that they spoke German and were philosophically active during the 1920s, but that is about it. Heidegger and Cassirer met and traded rhetorical blows at a celebrated philosophy conference in Davos; Benjamin was envious of Heidegger’s success and Wittgenstein at least had heard of him. But they were all ploughing very different furrows — unless you ascend to the highest levels of abstraction and say, along with Eilenberger, that they were all interested in human beings’ relationship with language. Well, sure. Aren’t we all?

The book starts at the end of its chronological period: in 1929, Wittgenstein receives his PhD at Cambridge, while Heidegger and Cassirer arrive at Davos, and Benjamin is ‘troubled by concerns of quite a different order’ — his girlfriend has just kicked him out. So the book’s structure is established, cutting between the lives of its four subjects with increasingly elaborate paraphrases of the concept of ‘meanwhile’. (At one point we switch from Benjamin worrying about money to Wittgenstein, who ‘was also preoccupied with his finances, albeit in a different way’.)

It is nonetheless an enjoyable read, partly because of the author’s love of gossipy detail and partly because he clearly adores the work of his subjects — particularly that of Wittgenstein and Benjamin, the latter of whom he is intent on defending for his ‘seemingly idiotic array of themes and interests’. As Eilenberger enumerates them, Benjamin’s subjects ranged from

Jewish numerology to ‘Lenin as letter-writer’ to children’s toys; brisk reports on food fairs or haberdashery joined long essays about surrealism or the châteaux of the Loire valley.

In other words, Benjamin was a working man of letters as well as the inventor of cultural studies, and from this historical distance seems by far the most modern of the book’s subjects: a hero of the cultural precariat avant la lettre.

Meanwhile (see what I did there?) we witness Heidegger having his storied affair with Hannah Arendt and spending prime thinking time in his forest hut, while Wittgenstein abandons philosophy to teach children in a remote village and write a dictionary for use in primary schools, though all the while exchanging letters with luminaries such as Keynes and Frank Ramsey. (During this period Wittgenstein habitually dressed in the same leather coat, lederhosen and heavy boots, and was apparently rather smelly.) Cassirer, on the other hand, leads an unruffled professorial life, writing on the ‘symbolic forms’ — art, science, religion — that make up human culture, while occasionally enduring anti-Semitic outbursts from his neighbours. (The book treads very lightly — perhaps excessively so — in its adumbration of the 1930s.)

In the end the reader is prompted to wonder whether it was indeed these four men, and only they, who ‘invented modern thought’. Plenty of other candidates of the era come to mind, philosophical and otherwise — why not Niels Bohr and the other quantum physicists? (As it happens, Cassirer wrote a well-received book on Einsteinian relativity, as well as a later treatise on the idea of indeterminacy in quantum mechanics.) As for Heidegger, his membership of the Nazi party is still in the future as the book closes, and so Eilenberger absolves himself from having to address the thorny question of what that episode means (if anything) for an assessment of his philosophy.

But one possible such assessment is surely closer at hand, and illustrates the eccentricity of attempting to tie these disparate thinkers together. The only known occasion on which Wittgenstein mentioned Heidegger was to say to a friend that he knew what Heidegger meant by ‘being and anxiety’. But had old Ludwig been forced to read the scores of pages here of Heideggerian exegesis about ‘being’ and ‘Dasein’ and ‘es gibt’ and so forth — the dullest parts of the book, and predictably so, since no known alchemy of prose exegesis could render them exciting, unless it be to point out that they at least constituted a useful theoretical defence of Heidegger’s extramarital shagging habits — he would surely have consigned it all to the category of apparent philosophical problems that are simply products of our bewitchment by language. The heroes of this book might all have been magicians, but they had very different concepts of what should count as an illusion.

Comments