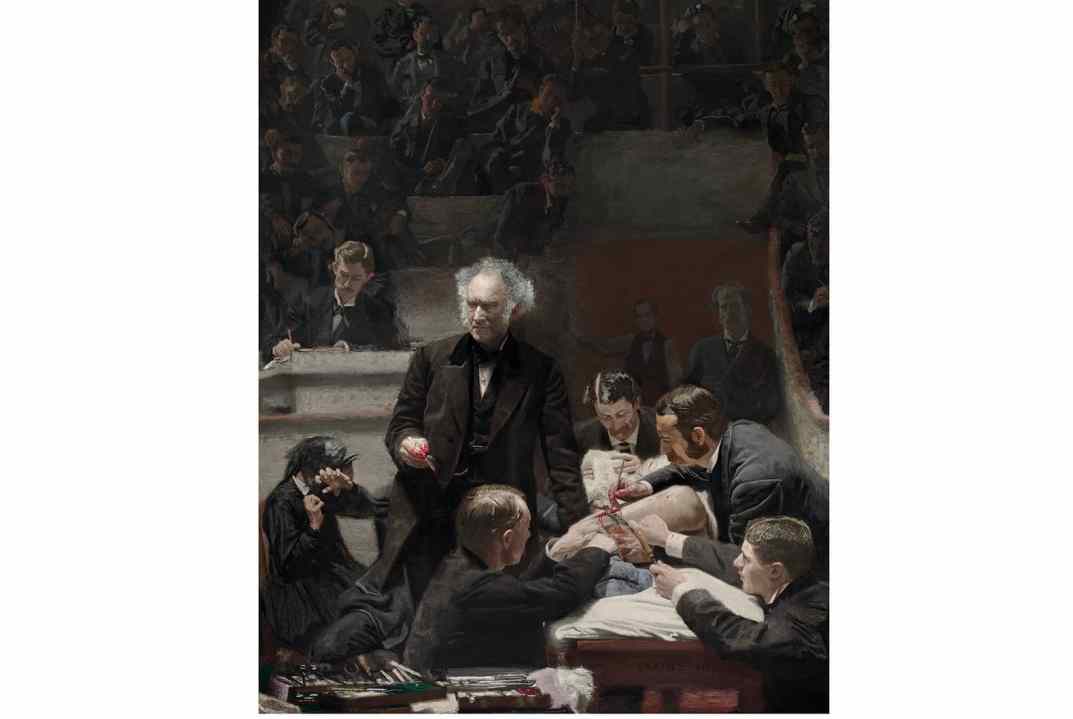

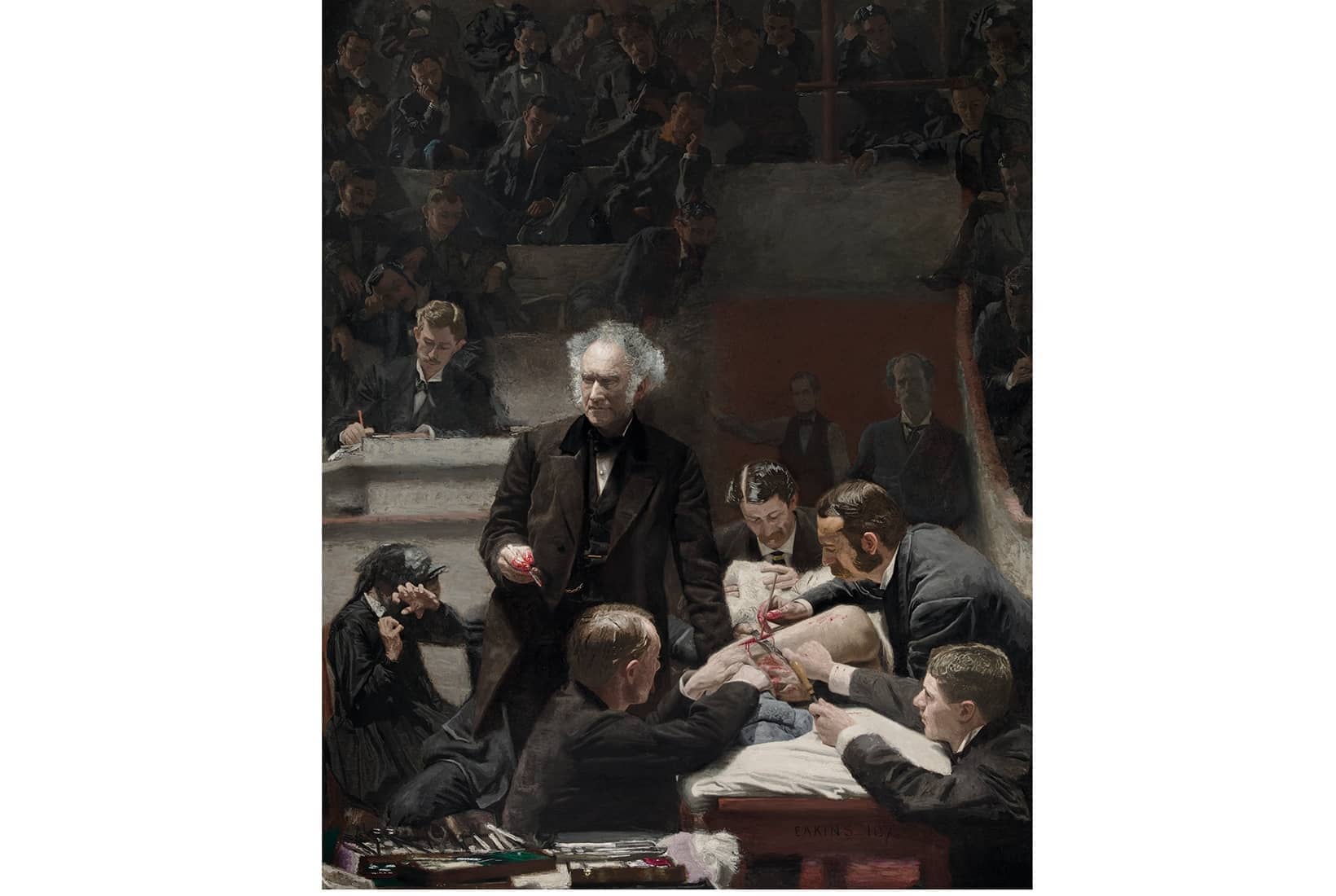

A doctor with wild grey hair and mutton chops holds a scalpel in his bloodied hand. He has paused for a moment, allowing one of his students to take his place and complete the incision. It’s a remarkably clean cut; the young man with the clamp has barely dirtied his shirt cuffs. Even so, the patient’s mother, if that’s who she is, weeps in the corner. She can see nothing but frock coats and a segment of open flesh.

The 19th-century Philadelphia-based artist Thomas Eakins did not paint surgery as it was, exactly, but he did capture something of its veiled sterility. There may be no gowns or masks in his earlier medical pictures, but the wool coats and shirts worn by the doctors only do so much to soften the atmosphere of the operating theatre. The overriding impression is one of detachment. The doctors may be just an inch from their patients, the scribes not a lot further away, but emotionally, they exist on a different plane entirely.

‘Plus ça change!’ some will sigh at the pitiful lack of bedside manner on display in many such pictures. But isn’t that why we need medical art? To be reminded that scientific progress isn’t everything; that medicine is fundamentally about one human (or humanoid robot, as it may now be) helping another? In ‘The Gross Clinic’ (1875), less unedifying than its title suggests, Eakins emphasises the relationship between teacher-surgeon Samuel Gross and his male pupils over the relationship between the group of them and the dehumanised patient on the table. Gross would need to stand back and look at the painting to appreciate how quickly a human can be mistaken for a body.

The difficulty for many early surgeons was that they were more used to performing operations on corpses than on living people. A new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland contains numerous pictures of men delving about in dead bodies before procedures on the living (other than amputation and the odd excision) even seemed viable. Eakins’s paintings do not feature, but ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Willem Röell’ (1728) by Cornelis Troost, an actor-turned-painter of 18th-century Amsterdam, does. It shows five men in wigs and buttoned-up silks posing by a corpse they’ve torn open through the leg.

It is thought that Leonardo dissected more than 30 corpses in the course of his career

‘The anatomy lesson in progress is a very bloodless affair,’ says Dr Tacye Phillipson, lead curator of the show. ‘There’s a sanitising effect of transferring flesh to oil.’ This effect is clearest in artists’ depictions of the doctors themselves. As Phillipson adds, ‘There was a really elegant delineation – they sanitised what was an insalubrious science. We see how the surgeons wished to be portrayed.’

One such surgeon, a pioneering 16th-century Flemish anatomist named Andreas Vesalius, was only too happy to be depicted performing a dissection of a woman who’d claimed she was pregnant in order to put off being executed. A professor of anatomy at the University of Padua, and later court doctor to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Vesalius used the image as a frontispiece to his influential treatise, On the composition of the human body in seven books (1543). An enormous crowd of men (plus a few dogs) are shown gathering around to watch him perform the feat. They whisper, they point, they lean forward to get a closer look.

If you can get past the weirdness of this, there’s something almost touching about seeing humans peer into the body of one of their own kind in a frenzied attempt to understand their own make-up. Members of the public were allowed to join future medics at many anatomy lessons for a fee. The first demonstrations took place in Padua and Leiden at the close of the 16th century. The experience was quite different from a day at the gallows. One senses from the facial expressions of the onlookers that they came for more than the gore.

The Edinburgh exhibition examines the often desperate means by which artists and scientists acquired their own knowledge of internal anatomy. The history of grave-robbing and of Edinburgh’s notorious Burke and Hare murders of the 1820s, which saw the bodies of innocent victims sold to a surgeon who ought to have known better, is told alongside a selection of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings.

It would be fair to say that Leonardo’s work has done more than that of any other artist to challenge medical knowledge. As the catalogue to the exhibition explains, he showed that there are four chambers in a human heart, not two, and understood how blood flowed in and out of them. It would be 1925 before the first heart-valve operation took place (it happened in Middlesex), but looking at Leonardo’s studies, you could well believe he’d had a good stab at performing one himself. He could not have produced a fraction of these studies without actually handling human organs. It is thought that he dissected more than 30 corpses in the course of his career.

Gunther von Hagens is the obvious heir to the artist-anatomists of past centuries but leans more towards science than art. The German’s ‘plastination’ of bodies and body parts, which serves to preserve real flesh, is for some people the stuff of nightmares. Are the crowds who stand and marvel at the results in the various manifestations of Von Hagens’s Body Worlds exhibition so very different from those who paid to watch live dissections in the age of enlightenment?

The anticipation of looking beneath the flesh is admittedly often worse than the reality. Some of the most intimate hospital art of the 20th century was produced by Barbara Hepworth after she was invited to the operating table by the surgeon who’d treated one of her daughters for osteomyelitis. While Hepworth’s initial reaction to the idea was ‘one of horror’, she soon realised that there was ‘a very close affinity between the work and approach both of physicians and surgeons, and painters and sculptors,’ not least in their ambitions for perfection.

Her ‘Hospital Drawings’, made between 1947 and 1949, present the surgeon as an artist. His hands are those of a sculptor. His scalpel is a modelling tool. He sews like a tapestry-maker with needle and thread. Apart from the surgeons’ hands, Hepworth was drawn to their eyes, their other main tools for communicating when they are swathed in PPE. They stare out over their masks in unblinking concentration.

Hepworth’s doctors almost rival the gentlemen of the early anatomy lessons in their pristine pastel uniforms. Cleanliness certainly has an enduring appeal. The body may be hot, chaotic and overflowing with the proverbial humors, but most of us would sooner think of it as tidy, balanced and manageable. This is why Damien Hirst’s ‘Pharmacy’ (1992) and ‘Pill Cabinets’ and, more recently, Lucy Sparrow’s ‘Bourdon Street Chemist’ (2021), constructed entirely from felt, look so inviting. Where other medical art distorts the reality by sanitising it, neat rows of bottles and boxes seem to promise that order can be restored to the mess already deep inside us. Just pop the lid and swallow.

There may no longer be any need to document operations artistically when some of the most pioneering are filmed for professional purposes, but many artists continue to find inspiration in the operating theatre. In non-Covid times, when access is easier, why wouldn’t they? It may be clichéd to say that the hospital is where they can witness every moment from life beginning to life ending, but it’s true. As Phillipson says, the ‘visual fascination of ourselves with ourselves’ is the one thing that will never die.

Anatomy: A Matter of Life and Death is at the National Museum of Scotland until 30 October.

Comments