The most remarkable thing about this book is that it should have been published at all. No one could have imagined in 1961 that Private Eye — a blotchy reproduction stapled together on what looked like yellow scrap paper — would still be going 50 years later, selling hundreds of thousand of copies every fortnight and apparently employing about 50 people. Adam MacQueen has not written a history of the paper but has compiled a biographical album of contributors, staff, stories and various dramas in its history. The author suggests that it could be read from cover to cover, but that would be hard work even for a satirical anorak. It is much better approached on a random basis, following the cross-references or just leafing through it.

I wasted a large part of my life working at Private Eye between 1966 and 1978, and it was a most enjoyable experience. I was fortunate because that was a golden age for the magazine. Nothing is more tedious than rheumy-eyed pensioners moaning on about the good old days, but the Eye has never regained the fire and political influence it had for a few years in the 1970s when the cast list included Peter Cook, Willy Rushton, Auberon Waugh, Barry Humphries, Gerald Scarfe, Christopher Logue, Paul Foot and Michael Gillard.

That is partly because such talent is rare, but also because Private Eye necessarily reflects the society and press of its time. It prospered then because it could fill the vacuum encircled by a deferential political lobby, a prudish national and weekly press and the grotesque laws of libel. For a number of years it was required reading in Westminster, Whitehall, the City and throughout educated society, the only way to understand ‘the real England which lies hidden beneath the rubbish one normally reads’, as Bron Waugh once put it. Although it is still very popular, the magazine does not play that role today.

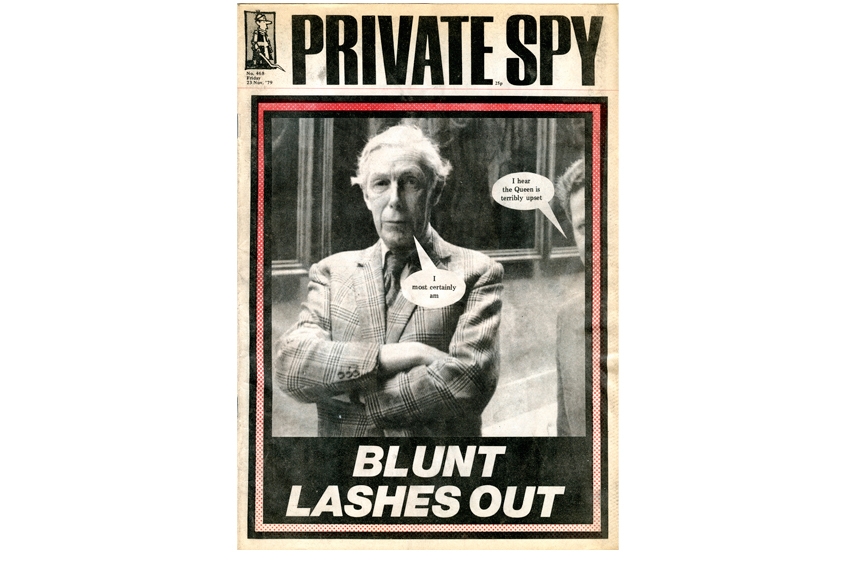

The traditional form of attack faced by a paper that broke the rules was of course the libel action. The editor, Richard Ingrams, developed a skilful way of dealing with these attacks, and somehow managed to give most people the impression that anyone who sued Private Eye for libel obviously had something to hide. This worked well until the offensive launched by Jimmy Goldsmith in 1975. Goldsmith notoriously issued 63 writs and brought 27 different cases, and said that he was prepared to spend £250,000 to close the magazine. He appeared to be the champion of a colourful coalition of dodgy Labour politicians, sleazy PR men and professional gamblers, but was in fact determined to stop ‘City Slicker’ from investigating his complex financial activities. He was a brutal and ruthless operator who was prepared to drive men who crossed him to commit professional suicide. Private Eye was saved by its readers and by the editor’s fortitude, but not before Ingrams and I had to appear in the dock at the Old Bailey. The strain of the case took most of Ingrams’s pleasure out of the job (see entry ‘Goldenballs’) and eventually led to his resignation and the arrival of Hislop.

Private Eye has always been dominated by its editor, and the magazine has only had two real editors, Richard Ingrams and Ian Hislop, which in the course of 50 years is remarkable in itself. (One can discount Christopher Booker who was editor for about two minutes in 1962. )

The paper today reflects the personality and ability of Hislop just as faithfully as the Eye of the golden age reflected that of Ingrams. Under the heading ‘Editors, fundamental differences between’, MacQueen suggests that Ingrams was a trouble-maker, whereas Hislop is more of a Swiftian satirist lashed by savage indignation. That sounds to me as though the latter has started to take himself rather seriously. I never worked with Hislop, but after reading this book I can think of other more obvious differences. Hislop appears to be politer, more anxious to be liked, more curious, less easily bored, more self-confident and far more willing to give credit where it is due. But he has a nasty little temper on him. He seems to be quite proud of his ability to lose it and start shouting at his employees.

I do not recall Ingrams ever losing his temper. He had a gentle personality as editor, and a very good relationship with people he could rely on, people who offered him devoted admiration in return. On the other hand, his boredom threshold was absurdly low, and he was jealous of other people’s ability and very reluctant to credit their achievements. He did not appreciate the attention paid at various times to John Wells, Paul Foot, Gerald Scarfe or Bron Waugh, which was ridiculous, because the magazine suffered as a result.

More importantly, Ingrams is much the funnier of the two. The brief speech he made last month at the Guildhall celebrations of the magazine’s 50th birthday — sandwiched between never-ending orations from Booker and Hislop — was Ingrams at his best: perceptive, original and extremely funny. He is a very complex person, temperamentally rather idle, possibly depressed, inspirational, religious, troubled. Some day someone will write a brilliant biography of a man who has played an important role in his times. But it will have to be a male biographer — women are far too inclined to cherish him — and it will have to be someone who is free of hero-worship and able to make their own assessments.

The dead do not always come out of The First 50 Years too well. The late Mary Ingrams was not a ‘manic depressive’, full stop. When I first met her she was a very attractive young woman who adored her husband and was battling, successfully, to bring up a young family in a very small and rather remote cottage on the Downs. Fact. (Or five facts.).

The late Nicholas Luard, the second Lord Gnome, was clearly not a talented man of business but neither was he some sort of absconding cashier, as MacQueen has apparently been led to believe. Luard was clever and creative and his comment that there was ‘bad chemistry’ in the office and that ‘they were always at each other’s throats’ was perfectly true of the magazine in 1963. The problem was solved when Ingrams, Willy Rushton and the business manager Peter Usborne fired Booker.

The entry on ‘Colonel Mad’ (the late Jeffrey Bernard) is far too short and has certainly not got to the root of the problem between Jeff and Ingrams. To say that Jeff was ‘a boozer’ must be the understatement of the year.

The late Nigel Dempster, who fell out with Hislop very early on, is given a lengthy sandbagging, which could have been done just as effectively in a quarter of the space. Dempster’s behaviour was increasingly strange for some years before he was diagnosed with a fatal brain disease, but this explanation for the poor man’s decline is given short shrift. It is striking how the original tendency towards feuding continues today, with the new team inheriting all the ancient grudges.

The late Auberon Waugh does not even have an entry of his own, and is made to carry the can for a lot of stuff (now described as ‘regrettable’) that did, after all, appear with the Ingrams imprimatur.

Many people, politicians, other journalists, most of those in public life, are afraid of Private Eye and its editors know that and have made use of it to discourage criticism. So what can be said about ‘the national treasure’, (as Ingrams refers to his successor)? One has to admit that Hislop has made a huge success out of his task, and the paper seems to be as popular as ever, or more so.

By linking his editorship to his career as a television personality, Hislop has ensured both his own and the paper’s commercial success.

His fans will no doubt be delighted by the many photographs of him that appear in this book. Indeed he pops up all over the place. You think you are getting a short break and there he is again, just in case you had forgotten what he looks like. I lost count of the number of headings which set out to cover a subject — Youth, Look-alikes, Moron, Cook (Peter) — which suddenly metamorphose into further aspects of Hislop. This is a clear example of the rule More means Less.

I would have traded about 200 Hislops for an index, which would assist readers to follow particular lines of enquiry.

My own account of the early years, The Private Eye Story (1982), enjoyed editorial independence, unlike this book, and was withdrawn by Ingrams shortly after paperback publication as a result. This outrage did not, however, lead to my departure from the magazine, as MacQueen states repeatedly. That departure had taken place amicably some years earlier, and by the time my history appeared I had been working at The Spectator for two years.

Since The First 50 Years is published by Private Eye Productions, and since the author is an Eye staff reporter, there is little risk of his book suffering a similar fate. But despite the problems posed by a lack of independence, MacQueen has done an excellent job with this compilation. He has waded through a lot of research; 50 years is an awful lot of issues even for a fortnightly, and he frequently provides an admirably thorough and objective account of some quite tricky moments, (e.g. ‘Happy Ship, Not a’, ‘Most unpleasant thing in British journalism’, or ‘Resignation’).

And most of the book is great fun. The extracts from Auberon Waugh’s Diary, and the works of Barry Fantoni and John Wells easily withstand the test of time. And the cartoons alone — from Heath, McLachlan, Austin, Rushton, Reeve and many more — make it the perfect Christmas book. For a collector of rarities there is a photograph of my old comrade-in-arms, Michael Gillard, seated at his typewriter on page 219. He has greatly changed, as have we all.

Comments