Confusion abounded this week when the new German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said that Ukraine could use western missiles to hit targets deep within Russia. ‘There are no more range limitations for weapons delivered to Ukraine. Neither from the Brits, nor the French, nor from us. Not from the Americans either,’ he said. The problem was twofold. Firstly, that is not the official policy of western allies. Secondly, Germany has not provided Ukraine with any long-range missiles.

Partly that is a political choice by Germany, but there is also the fact of the inherent weakness of the Bundeswehr itself. Merz’s new government has recognised the limited nature of his military, vowing to build ‘the strongest conventional army in Europe’. For that to happen, the Bundeswehr will need more than money. It needs to know what it is and what it’s fighting for. Is Germany – still deeply scarred by its Nazi past – ready to build a military ethos fit for the 21st century?

Independent thinking has never been a priority for the Bundeswehr general staff. Rock-solid trust in US leadership was part of its very foundations. With those foundations eroding, Merz is trying to build his own as quickly as possible. He has promised to spend 5 per cent of GDP on the military and related infrastructure; this amounts to some €200 billion, four times what Britain spends on defence in any given year.

There is an irony in this promised military expansion: it’s the result of Donald Trump’s demands that Nato allies meet their obligations under the treaty. Even when it comes to greater German self-reliance, it seems that Washington is still calling the shots.

This historic reliance on American strategic direction is combined with a relaxed approach to the chain of command. The Bundeswehr is wary of discipline and blind obedience, which are seen as characteristics of previous German militaries, especially the Nazi Wehrmacht. So its self-declared ‘company ethos’ is that of a ‘citizen in uniform’ acting on his or her own ‘inner guidance’. In other words, soldiers are explicitly encouraged to question every order. ‘The Bundeswehr knows no absolute obedience,’ recruits are told. ‘The ultimate decision-making body is the conscience of the individual.’

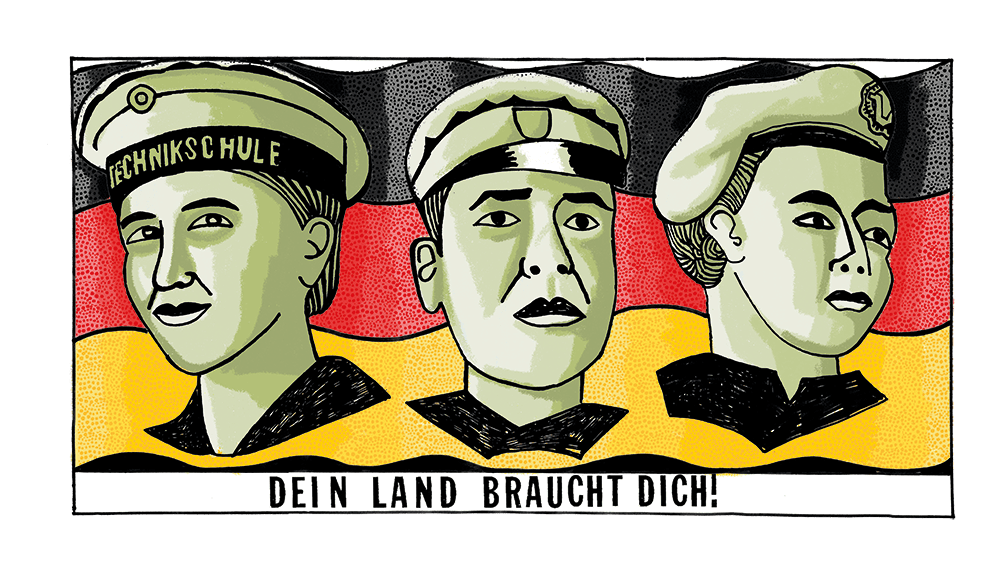

Germany’s military was a publicly funded employer whose focus was subsidised educational opportunities

This was a conscious break with the Prussian military tradition. Members of the Prussian aristocracy, or Junkers, had previously made up a sizeable proportion of the officer class. Their obedience to the monarchy came with a long-established ethos of strict military discipline. This allowed for the development of a more flexible command structure compared with European neighbours. Called Auftragstaktik or mission command, it involved the commander issuing an objective rather than a direct order on how to achieve it. His subordinates would then have a large degree of freedom as to how to achieve the objective. The Prussian military was highly trained and ideologically consistent, meaning that commanders could trust their underlings to follow military doctrine.

The Bundeswehr still largely relies on the Auftragstaktik model, but now minus the element of absolute structural obedience. It’s easy to see why. Wehrmacht soldiers committed terrible crimes on behalf of Hitler in a war that was explicitly genocidal. Commanders later claimed they were only following orders. The idea of an army of ‘citizens in uniform’ was that every soldier should have the capacity to stop such atrocities. Individual morality must exist, even within military command structures.

Perhaps that independence of mind is what led to a series of scandals within Germany’s elite Kommando Spezialkräfte. In 2020, the KSK was partially disbanded when members of the unit were found with Nazi memorabilia and evidence emerged of soldiers singing fascist songs. The then-defence minister said the unit had ‘become partially independent’ of the chain of command.

KSK members were found to have discussed the potential of a migration-induced civil war, while another was implicated in a 2022 attempted monarchist coup. Investigators found that some NCOs had compared the unit to a modern-day Waffen SS.

Those accused of these right-wing plots came from historically conservative parts of the country like Saxony and Thuringia. The KSK’s base is in a remote part of the Black Forest, which investigators said contributed to their insular mindset. As of 2021, no woman had passed the KSK commando soldiers’ entrance tests.

Fear of such scandals is what fuels the Bundeswehr’s many diversity initiatives. Women only gained access to all military roles in 2001, yet are now seen as ‘naturally equal’ and their presence as ‘a normality’. Accordingly, there has been a massive drive to push the proportion of female personnel from 13 per cent to above 20 per cent. The Bundeswehr holds annual ‘Girls’ Days’ in an attempt to recruit women into the military.

There has been a similar focus on changing the demographics of recruits. In a recent study entitled ‘Colourful in the Bundeswehr?’, the Ministry of Defence declared that ‘as a matter of principle, the way towards conditions of equal opportunities in any organisation goes through the furthering of a diverse and “colourful” body of staff’. The ministry is at pains to point out that it understands ‘diversity’ as a ‘holistic’ concept involving not just ethnicity but also other characteristics such as gender, age, disability, religion and sexual identity. Notably, for a country that reunified only 30 years ago, there’s no mention of regional or class diversity. Germans from poorer eastern states are excluded from such diversity drives.

The Bundeswehr presents itself as a regular civilian employer whose main concern isn’t operational effectiveness but the recruitment and retention of a civilian-like workforce. The ideal is an army that reflects society, but the downside is that it makes institutional loyalty an afterthought. If the Bundeswehr presents itself as a regular employer, recruits will treat it accordingly. They will come and go as they please and show reluctance to do jobs that are difficult, dangerous or less well-paid.

The recent report of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces of Germany revealed serious problems. It points out that since 2019, the average age of Bundeswehr members has risen from 32.4 years to 34 years. Efforts to increase the size of the military from 180,000 active soldiers to the target of 203,000 by 2031 have so far been unsuccessful. There has been an increase in the number of recruits but more than a quarter of them leave the Bundeswehr within six months. A survey of those who left concluded that most had done so because they found ‘a different alternative’; others said the job was ‘too far from home’.

The focus on personal work conditions has also led to a rather ‘top-heavy’ structure. A recent study of Bundeswehr applicants showed that despite the increase in absolute numbers, there is an acute shortage of those who want to join the rank and file rather than via the officer routes. The chief of the German army, Lieutenant General Alfons Mais, has complained that of the 180,000 members of the Bundeswehr, around 100,000 occupy officer staff or leadership roles. ‘They are watching from the stands while 80,000 are trying to win the war,’ Mais said.

These are long-standing structural problems of the Bundeswehr, issues that for decades no one thought needed fixing. If anything, politicians were happy for Germany’s military to be a publicly funded employer whose focus was subsidised educational and employment opportunities. One of my (female) German school friends signed up as an officer recruit because she wanted her university degree funded. She is no longer in the Bundeswehr.

It was deemed a success that the postwar officer class was no longer dominated by heel-clicking Prussian Protestants all recruited from the same aristocratic families. Today’s Bundeswehr leadership is instead distinctively middle-class. According to the recruitment study, applicants who considered themselves ‘middle-class’ or ‘upper-middle-class’ were vastly overrepresented.

It’s a demographic particularly interested in employment opportunities: the Bundeswehr runs two universities, in Hamburg and Munich, offering courses that have little to do with military tasks, including psychology and sports science. My former officer friend graduated with a degree in education after a few years in the Bundeswehr.

The somewhat transactional nature of recruitment never seemed a problem; the Bundeswehr was mostly a tolerated but unloved part of Germany’s restructured postwar order. There was enough funding to keep its uniformed citizens occupied and a firm conviction that they would never have to fight in costly, large-scale campaigns. This led to a neglect of the actual machinery of war: depleted ammunition, infrastructure, equipment and supplies. Under Angela Merkel, defence expenditure dropped to barely above 1 per cent of GDP.

Since the second world war, the German armed forces have rarely been deployed and when they were, it was always amid acrimonious public debate. In total, the Bundeswehr has lost 119 people on foreign missions since 1955 – which, while tragic, is extremely low compared with the losses of many of Germany’s partners. The UK has lost 7,193 since the end of the second world war.

In 2022, the then-foreign minister Annalena Baerbock argued that Germany was more reluctant to get involved in Nato campaigns ‘because we are not all the same – even though we are standing side by side, we have different roles and we have different history’. On the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine she still insisted: ‘This is not the moment to change our course by 180 degrees.’

Merz says that moment has now come. But with the weight of German history on his shoulders, he too will find it difficult to reform the Bundeswehr. No educational offer or recruitment campaign is a replacement for the ethos and traditions that bind soldiers to one another. Money alone will not make it a force for which the country’s young are willing to fight and potentially die. Only a sense of purpose, identity and comradeship can do that – the kind of military culture Germany’s postwar elite has always quietly feared.

Comments