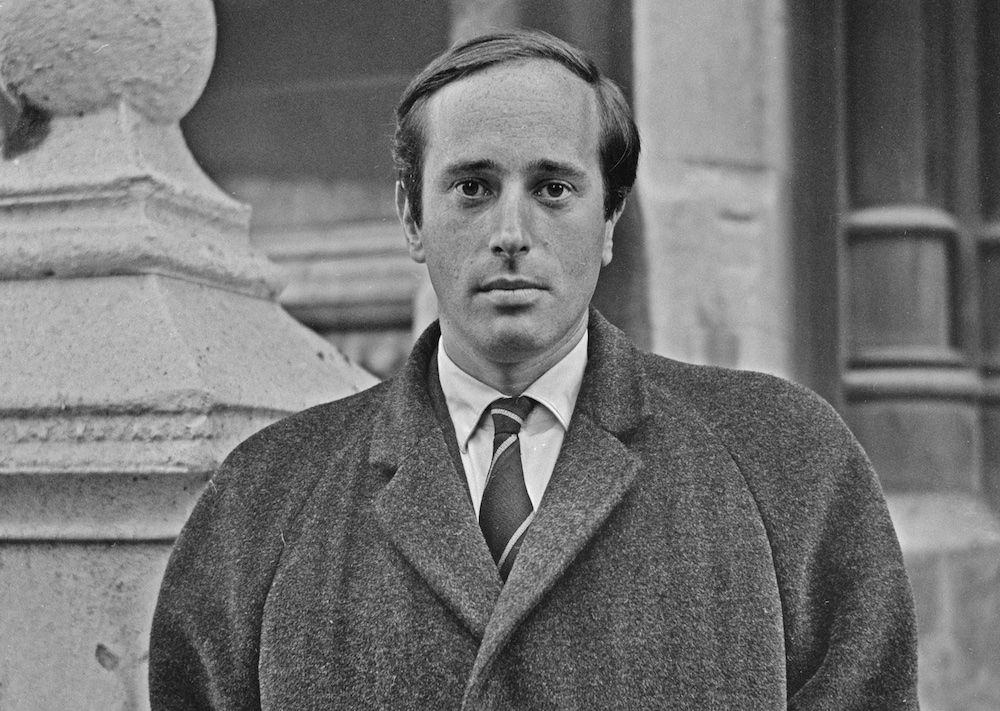

Brian Glanville, who died this week at the age of 93, was a unique voice in the crowded and often hysterical field of football writing and a uniquely important one. His historical reach was unparalleled. He published his first book (a ghosted autobiography of Arenal striker Cliff Bastin) at the age of 16 and attended 13 World Cups, starting with the 1958 tournament in Sweden.

His lean, elegant, novelistic style, informed by his parallel career as a fiction writer, could be found nowhere else in the UK. As Patrick Barclay put it, ‘most football writers fall into two categories: those who have been influenced by Brian Glanville and those who should have been’.

Glanville was simply different. For one thing, he was, to not put too fine a point on it, a ‘toff’. In an industry dominated by tough, plain-speaking and working-class journalists, that stuck out like a top hat at a miner’s gala.

This was important for me, as a rather serious and sensitive (opera loving!) middle class teenager in the gritty urban environment of the west of Scotland. Football culture, dominated by Celtic and Rangers, tended to be on the rough side and it was tempting to head to the genteel environs of the cricket or rugby club. Perhaps football wasn’t for the likes of me?

Glanville gave me the confidence that it absolutely was. Football was for everyone. And not only could we go, we could go with our heads held high. Glanville saw no need to disguise his old Carthusian background, literary leanings or broad cultural knowledge. He just loved the game so he went along, and wrote about it, in his own graceful, witty and opinionated way.

He wasn’t a snob. In fact, he may have been the victim of snobbery. Glanville almost never appeared on TV due, I strongly suspect, to a weird reverse class prejudice. He just didn’t fit the profile. I saw him appear just once, on a Scottish sports panel discussion hosted by Archie McPherson. A froideur pervaded the set every time he spoke in that languorous plummy drawl. The host and other panellists seemed to regard him as if he had come from another planet.

Yet, whereas other gifted sport writers like McIlvanny, Arlott and Cardus were reluctant to work for tabloids, Glanville happily wrote for the Sunday Times and the People, though in the latter he acknowledged that ‘literary illusions were not encouraged’.

He appreciated good writing wherever it was to be found. He admired fanzines, including, I was ego-strokingly thrilled to discover, Scotland’s The Absolute Game (‘refreshingly abrasive’ he called it) where I had my very first published piece. And this despite a weekly column (‘Bruno Glanvilla’) that lampooned him mercilessly.

He clearly adored language. In an essay for Prospect magazine, Glanville expressed a desire for an idiom that could be read ‘by intellectuals without shame and by the working man without labour’. He said no one in the UK had cracked this tough nut, but Glanville surely came closest. Influenced by such omnivorous polymaths as Runyon and Lardner, he utterly rejected the false dichotomy of sports and ‘serious’ writing.

He was also searingly honest and unafraid to take unfashionable positions

Having lived in Italy and written for Corriere dello Sport for many years, he recognised this as a particularly British conceit. Of Italy he wrote ‘readers are treated as literate, while the English tabloids have seldom ceased to treat their readers as morons’. He would roll his eyes at the fuss made over Nick Hornby’s supposedly ground-breaking ‘serious’ football book Fever Pitch. He slipped a quote by Keats into a match report once.

Certain of his phrases have stayed with me – I’ve quoted his ‘bloated incubus’ to describe the FIFA’s ever expanding World Cup several times. I also loved his description of Geoff Hurst’s ‘it’s all over now’ strike in the 120th minute of the 1966 World Cup final with Germany as a ‘terrible’ (in the true sense of the word) ’left-footer’. There are many, many more.

He was also searingly honest and unafraid to take unfashionable positions. He spent most of his career railing against the iniquities of FIFA president’s Havelange and Blatter, and the vacillations and compromises of the perfidious FA. He wasn’t much impressed with women’s football, and had little time for David Beckham, lamenting the day he overtook Bobby Moore’s record of England caps for an outfield player.

This honesty cost him, though. For all his love of continental football writing, he described as ‘craven’ the behaviour of his hero the Italian journalist Gianni Brera – ‘a whole man whose subject happens to be sport’ – when he refused to involve himself in the Lobo-Solti bribery scandal that Glanville had covered extensively for the Sunday Times. The two men exchanged ‘bitter words’ and never reconciled. He hated cheats and cowards.

It may even have prematurely ended his career. Glanville stopped writing some years ago, and appears to have simply withdrawn from the arena. Frailty perhaps, or was there no longer a place for his particular directness? It’s certainly hard to think of a warm welcome being offered in a Premier League press conference for a man who described the division (repeatedly) as the ‘greed is good league’.

And yet, who could seriously deny this important and perfectly expressed (very Glanville) truth?

Comments