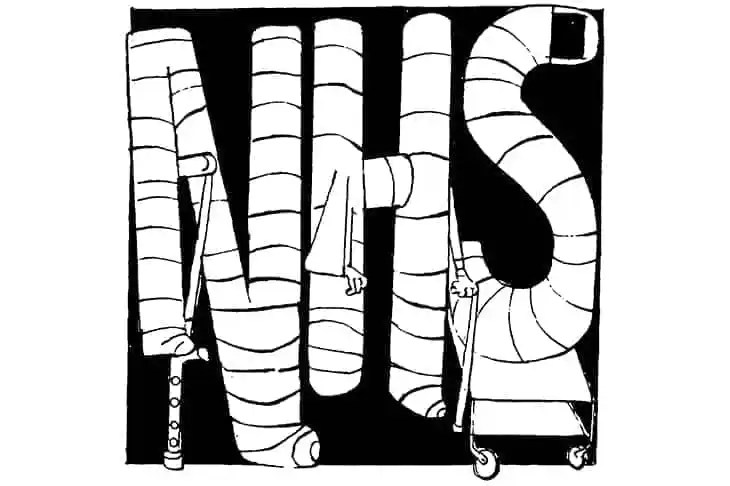

Today is the 75th anniversary of the National Health Service. There is very little to celebrate. Waiting lists are at record highs: 7.4 million waiting in England, and counting. Practically every international comparison ranks the NHS as mediocre to poor on outcomes. Well-above average funding is being funnelled into the health service, yet it doesn’t seem to be making its way to staff salaries or to the frontlines for additional care.

What’s worse, all these criticisms applied to the health service before the pandemic hit. The further deterioration of services since Covid is bringing to light all of its current – and previous – failings, as people increasingly ask if the system is fit for purpose.

The NHS’s most avid supporters are running out of explanations – and excuses – for its poor service. No one seriously claims anymore that the NHS is the ‘envy of the world.’ Certainly no international ranking says so. But there is one pillar that still seems to be holding up the NHS shrine: the argument around historical funding.

The NHS may be receiving a record amount of cash, the logic goes, but it was starved during the Tory party’s austerity years. Now, it can never catch up. ‘If you have a look at the investment that government should have put in,’ said Dr Phil Banfield, chairman of the BMA UK council, leading up to the birthday this week: ‘If they were investing up to the European average over the last 10 years, they’re over £40 billion short.’ In other words, the damage is done: if only 13 years of successive Tory governments had funded the health service as well as neighbouring countries did, the NHS would be on top.

This last line of defence makes a very basic – and almost universally accepted – assumption: that compared to other developed countries, the NHS has been underfunded by the government for over a decade.

Is this true? Real terms spending on the Department of Health and Social care (of which some 85 per cent goes on the NHS) has increased every year since 2010 (until the pandemic hit), albeit at a notably slower rate during the David Cameron years compared to the Tony Blair years: 2 per cent vs 6 per cent. In some cases, this has led to inaccurate claims that health spending was slashed during the austerity years (it was ring-fenced and increased).

But more broadly, it has given the impression that the UK government was falling behind its counterparts, lagging in its government funding for the health service.

That impression is wrong. On the contrary, every year since 2010, the UK has ranked in the top four countries in the OECD for government spending on healthcare. For the past three years no OECD government has spent more as a share of GDP. In the year before the pandemic hit, never before had the government spent more per person on healthcare. In 2011, the first full year the Tories were in charge, the UK ranked third for government spending, with 8 per cent of GDP going on healthcare. In 2015, the height of Cameron’s austerity programme, the UK still ranked fourth with 7.9 per cent of GDP.

The lowest point of government spending over the past 13 years was in 2017, when the total came to 7.7 per cent of GDP. Still, the NHS held the fourth position in the OECD ranking. The only countries whose governments consistently spend more than the UK are Scandinavian – fairly unsurprising as these are also often highly centralised systems, heavily reliant on taxpayer funding.

These numbers explain how the NHS has moved from taking up just under 30 per cent of day-to-day public service spending in 2010 to being on track to account for half of such spending in a few years’ time. That’s not just the NHS budget continuing to balloon while government spending flatlines – overall government spending is 20 per cent higher than in 2010 in real terms and day-to-day spending on services is up by around 15 per cent. You don’t get to such levels of spending without turning the country into a health service with a government attached.

Why, then, did the UK rank lower down the league table for overall health spending during the 2010s (it jumped to ranking above average for overall health spending towards the end of the decade, and now sits in sixth position post-Covid)? How to explain that missing £40 billion, mentioned by Dr Banfield?

Long before Covid hit, the NHS was already losing thousands more people with common types of illness and cancer than neighbouring systems

This is where the system – and the politics around it – comes in. The NHS is by no means the only system which offers ‘universal access’ to healthcare. Indeed, almost every developed country in the world does this. The United States is the exception. But unlike in the UK, ‘universal’ has not been interpreted as almost-solely taxpayer funded. There has not been an attack on the ethics of market mechanisms in healthcare, or more being paid into the system by those who can afford to do so. This has allowed other countries to inject lots more money into their systems, creating a combination of public and private funding (often through social health insurance schemes) that not only provides for everyone, but crucially, gets them faster access to better care.

Overall healthcare funding for the NHS in the 2010s was broadly in the middle of the pack – not because of a lack of taxpayer investment, which each year ranked to be some of the highest in the world – but rather because of an ideological obsession over how the health service must be funded (or, in this case, how it should not be funded: with top ups of private sector cash). The irony over this militant morality that has been allowed to dominate health policy for decades is how many lives have been lost to defend it.

Long before Covid hit, the NHS was already losing thousands more people with common types of illness and cancer than neighbouring systems. The King’s Fund found last week that the NHS comes second-to-last in a list of 19 developed countries for saving lives with ‘treatable’ illness; third-to-last for ‘preventative’ illness.

This is not a result of government underfunding or system-starvation, but rather an unwillingness to update the model and funding streams of a 75-year-old system of healthcare that was proudly labelled a socialist invention, and has since its inception been delivering predictable and devastating socialist results.

Comments