Novice chess players can seem spellbound by the power of their own queen, zigzagging hither and thither in desperate search of bounty. You soon learn that on the chessboard strength is weakness and weakness is strength; the queen must flee from any attack while a pawn is, well, only a pawn in your game. Experienced players acquire a more mercantile approach – every piece has its price. In fact, being ready to dispense with an ostensibly valuable piece in service of a higher goal is the mark of a skilful player.

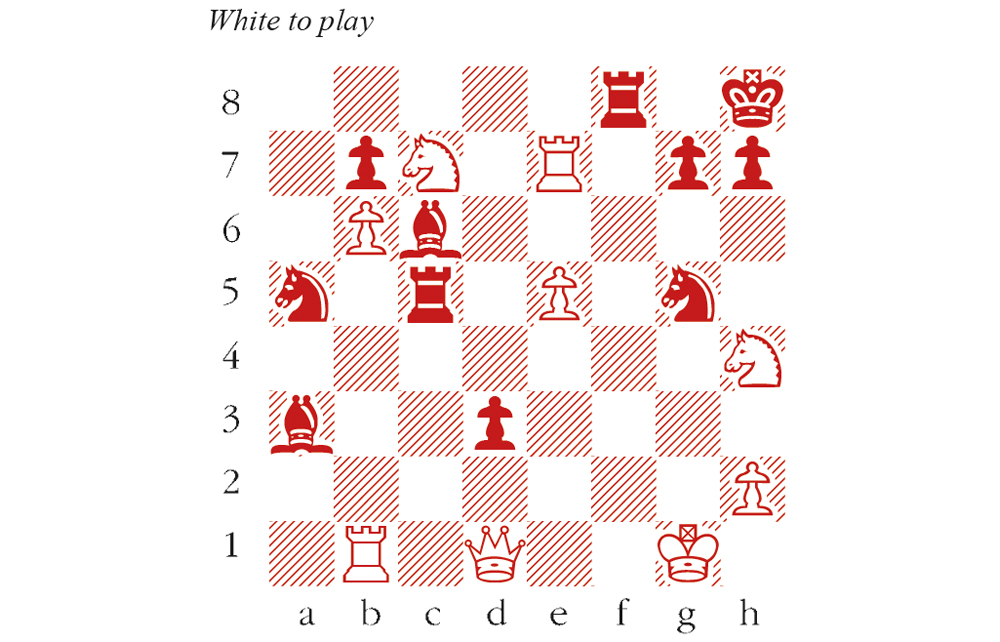

Making great play of this is the chess game from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, presumably one of the most widely viewed chess scenes in cinema history. The American international master Jeremy Silman, who died aged 69 in Los Angeles last week, devised the sequence which begins at the diagram below.

On their quest, Harry, Ron and Hermione become embroiled in a game of wizard’s chess. The intrepid trio take their places as a bishop, knight and rook respectively on a giant chess board. This is a hazardous undertaking, since their fellow combatants are stout warriors carved from stone, which execute their captures with all the finesse of a wrecking ball. Naturally, it is crucial that Harry is kept alive.

Harry is the bishop on a3, Ron the knight on g5 and Hermione the rook on f8. The white queen is the villain, who captures 1 Qxd3, bearing down on Harry, while simultaneously guarding against Ng5-h3+. Fortunately, Ron is a strong player, and the next move is brilliant: 1…Rc3!! inviting another demolition job from the white queen. 2 Qxc3 crashes closer to Harry and sets up the climax. In pure chess terms, 2…Bc5+ 3 Qxc5 Nh3 would be mate. The snag is that Harry is not expendable. Ron knows this, so he performs the ultimate act of chivalry in the service of his friend: 2… Nh3+ 3 Qxh3 leaves Ron unhorsed and motionless on the ground (spoiler: he survives), allowing Harry to deliver the coup de grâce: 3…Bc5+ 4 Qe3 Bxe3 mate.

Teamwork, self-sacrifice, and an elegant combination to boot. We know all this because Silman wrote about it, but alas, very few details of his careful choreography are discernible in the final cut. (Fancifully, I view the white knight on h4 as a neat counterfactual detail. If the evil army playing White had opted for 2 Ng6+ hxg6 3 Qxc3 in the sequence above, sacrificing Ron would then invite disaster, since Qc3xh3 places the black king in check. But chess-wise, 3…Bxe7 is a decent fallback.)

Jeremy Silman is renowned as a bestselling chess author. His book How to Reassess Your Chess (4th edition) is a perennial favourite among club players, with a well deserved reputation. (His other popular works include ‘Silman’s Complete Endgame Course’ and ‘The Amateur’s Mind’.) At 650 pages, How to Reassess your Chess is a hefty work, but Silman writes with great clarity and a light touch. He elucidates the main principles of chess strategy through his concept of ‘imbalances’ – primary positional features, such as a bishop versus a knight, weak pawns, and so on. The idea is that an astute appraisal of these imbalances will indicate the correct plan to pursue. A little dogmatic for some tastes, but Silman knew what he was doing. He described his concept as a ‘shortcut to pattern recognition’ – that is, a tool to help amateur players digest the vast array of strategic ideas in the middlegame. In his own words: ‘For example, when I harp on knights needing advanced support points, that idea/pattern sticks in a student’s head forever, ultimately allowing his hand to reach out and herd his horse to the promised land.’

Comments