When I think back to history lessons at school, the predominant focus was always on war. From the Battle of Hastings to the Battle of Agincourt, the Crusades to Nazi Germany, the curriculum seemed jammed full of stories about aggressive military affairs. Fascinating, but it was a relief to reach sixth form and discover another way to study the past — through a cultural lens, via the history of art.

History of art is often viewed derisively in the UK. It’s almost ignored by the state system, yet is offered by many independent schools. Because of this, it’s seen as a ‘posh’ choice, in much the same way classics is. A–level history of art is available at only 17 state secondary schools out of more than 3,000, plus a further 15 sixth-form colleges. By contrast, more than 90 independent schools offer it.

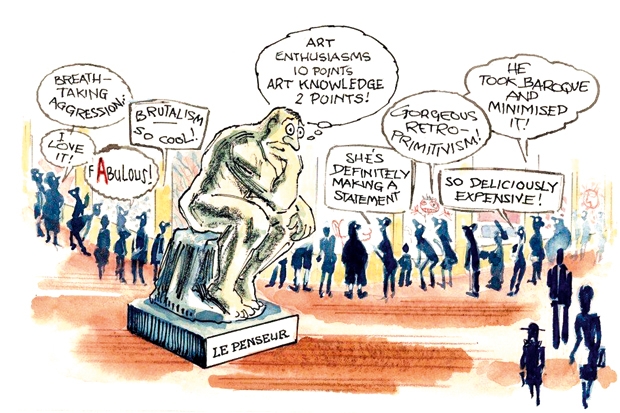

There’s no particular reason why history of art should be confined to independent schools — but for a long while it has been, and as a result, pupils from the private sector dominate university courses in the subject. Things aren’t helped by Kate Middleton (who studied history of art at Marlborough College and then at St Andrew’s) standing in front of Paul Emsley’s hopeless portrait of her in the National Portrait Gallery, saying it’s ‘brilliant… Amazing… Absolutely brilliant.’ Nice girls saying nice things about paintings that aren’t nice shouldn’t be the point of the subject. It’s a meaty one, when it’s allowed to be.

This is something which many of Britain’s independent schools recognise. Offering history of art allows them to include topics on the curriculum that traditional history lessons scoot round — the Belle Epoch, say, seen through the work of the Impressionists, or the Reform-ation, as examined through the Dutch Golden Age.

At Wellington College, pupils are trained to understand both their visual cultural heritage and the images generated by the modern world around them. They focus on ensuring that students are visually literate, and are set up for life in an increasingly image-centred world. Even students who don’t take history of art for A Level are aware of the discipline, thanks to art-focused assemblies built into the termly schedule.

At Westminster School, where they offer a Pre-U course, pupils are introduced to key artistic and historical moments from ancient Egypt to the present day. This includes an examination of both western and non-western artefacts. This holistic attitude is quite different to the more piecemeal approach of many standard history courses. Benjamin Walton, head of history of art at -Westminster, explains that this broad overview is combined with a far more focused second part — an examination of three historical periods: medieval, Italian Renaissance and late 19th/early 20th western European art. Study visits and a 3,000-word thesis tie all this together, creating a rigorous academic syllabus that is a particularly valuable experience for university.

Study visits are one of the most rewarding aspects of taking history of art. The halcyon days of the Grand Tour may be behind us, but many of Britain’s independent schools keep the flame alive. At places like Eton, Winchester and Godolphin & Latymer, students are invited to go on foreign trips that complement the course. Key hubs like Venice, Florence, Paris and Rome are popular, although more far-flung places like Istanbul and New York are sometimes included. There is much to be said for trips that allow pupils to get up close to objects. One girl from Marlborough fondly remembers an afternoon spent in the San Marco convent in Florence: ‘It wasn’t till you saw Fra Angelico’s frescoes in their original location that you began to understand how these contemplative paintings fitted into a simple monastic lifestyle.’

Foreign visits can be particularly helpful with architecture and sculpture. ‘Baroque architecture would have been tricky to get my head around without having visited Rome,’ says a pupil who studied history of art at Westminster. That said, for many, fond memories aren’t solely about the art; after a long day traipsing through a city, a glass of wine with fellow pupils and teachers can be just as memorable.

The best history of art courses will not only rely on this kind of extravagant trip, though. Britain is stuffed with all sorts of intriguing artefacts, and a course that only focuses on foreign collections is a dubious one. Visits to British museums and galleries can be just as enlightening. ‘The small-scale outings in London and elsewhere were actually far more important educationally than the big New York trip we went on,’ says a pupil who studied at Latymer Upper. ‘They allowed us to focus on individual works better, and were much more useful than charging around big foreign galleries, trying to make sure we saw everything.’

Take the National Gallery, home to one of the finest collections of art in the world. A good teacher can use it to introduce students to a broad range of artistic movements — from 14th-century early-Renaissance works to the flamboyance of the Rococo.

It is a shame that there’s so little recognition of this in the state sector — it does a disservice to students. Teachers could focus on art housed in Britain and still give an exceptional understanding of the subject. The legacy of centuries of British collecting, building and philanthropy has endowed this country with a mighty hoard of art. The study of this is an advantage that the independent sector continues to retain over the state system.

Comments