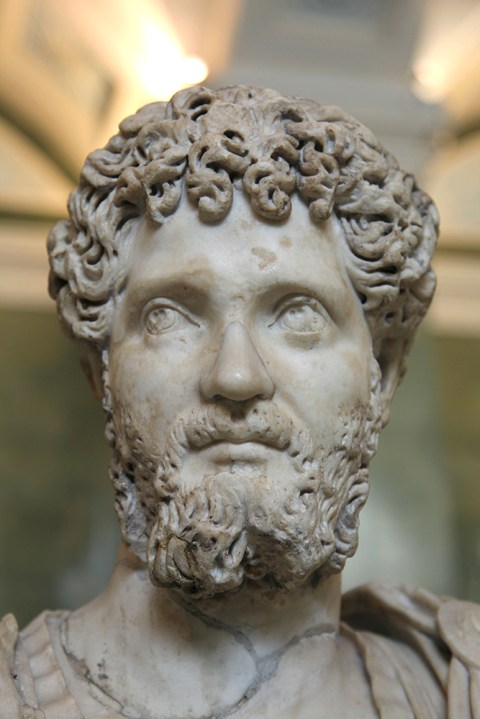

Rome’s first African emperor, Septimius Severus, was renowned during his reign (193-211 AD) for the mass killings of his rivals (ruthlessness even by ancient standards); for his genocide against the Scots (a rare recourse, despite Rome’s bad reputation as imperialists); and his budget-stretching generosity to his soldiers. He had an unusually glamorous Syrian wife, Julia Domna, who indulged her pet philosophers and her husband’s superstitions while setting a hairstyle trend. He had women Christians thrown to wild animals. His two sons, Caracalla and Geta, notoriously hated each other. The Roman empire ran economically while Severus was alive (with many old buildings repaired and renamed, as though Severus had built them) but collapsed into a century of chaos a few decades after his death. Simon Elliott, a military writer of books on Roman Britain, accentuates the positive where he can.

Septimius Severus killed senators on a scale that Nero had never come close to matching

Severus’s African birthplace did not in itself make him an unusual choice as emperor. Roman Libya was as Roman at the end of the 2nd century as Roman Greece or Gaul – and through the corn trade much richer. By murdering his potential enemies in Rome after publicly promising not to, Severus came to exercise more physical power than anyone born in Africa ever had or would, ruling an empire from the Firth of Forth to the Euphrates. That is quite enough of a claim for Elliott to justify the title of a book that does not confront the intellectual revolutions of the time, much of them in Africa, but examines every military campaign.

Severus rose to the top through the army. He became a senator and a provincial governor, but only by impressing his troops did he move to the front of the chaotic race to succeed the Emperor Marcus Aurelius’s manic son Commodus. Once Severus had defeated rival generals in clashes that included the greatest civil war battle in Roman history at Lyons in 197, he fabricated a story that he himself was the son of the author of the Meditations. But this was a tale only for the faraway. Severus ruled by horoscope and horror, killing senators on a scale that Nero had never come close to matching. Lest his enemies should read his stars, he had a false chart painted in a public room in his palace, the truth preserved only for his bedroom. His historian friend Cassius Dio won favour as a determined recorder of the supernatural. By war and wizardry, Severus brought wealth to Rome, which he divided prudently between the public treasury and his own.

Britain became a symbolic target. Severus’s most dangerous Roman rival, Clodius Albinus, had been based there. Though not a source of wealth beyond dogs and slaves, it was a stronghold behind whose defences plotters might plot again. It was the island where Julius Caesar had failed, where Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, had promised but not delivered, and where no Roman had conquered the furthest north. In 210, Severus led into Kent the biggest Roman force ever deployed against Britain. Elliott begins his book with a chilling promise, devotedly recorded by Dio, to all northern tribes who preferred living in swamps on strange beans to the comforts of southern civilisation. Not a single one of them was to be left alive, ‘down to the babies in their mothers’ wombs’. The whole people was to be ‘wiped out of existence, with none to shed a tear for them, leaving no trace’.

While many such an ancient boast was to impress the people back home more than the fact-checkers of the future, Elliott argues that there was a genuinely genocidal campaign that emptied the Scottish lowlands for generations. Meanwhile, Julia Domna, accompanying her husband for prophetic purposes as she almost always did, was free to play the anthropologist, patiently hearing from a tribal leader’s wife how British women openly satisfied their sexual desires with equals, while Romans preferred secret assignations with the lower orders. Or so Dio tells us.

In the south-east, London gained its first walls – still visible today – not so much to intimidate enemies, says Elliott, but to remind friends who was in charge. Britain also gained an official north-south divide, a line between the two parts of the province. It was on a visit to York, the capital of the uncivilised part, that Severus, aged 65 and immobilised by gout, died of British cold in 211. His last words to his sons were to ‘be of one mind, enrich the soldiers and despise the rest’ – advice which they followed, except in the first part. Caracalla, the more assiduous student of his father, had Geta killed and his face erased from every memorial he could find.

Comments