‘It is disastrous to name ourselves!’ So Willem de Kooning responded when some of his New York painter buddies elected to call themselves ‘abstract expressionists’. He had a point. Labels for movements — such as pop art, impressionism and baroque — are almost always misleading and seldom invented by the artists themselves. That was certainly the case with the idiom examined in a little exhibition at Tate Modern, Magic Realism: Art in Weimar Germany 1919-33.

Actually, this rather heterogeneous assortment of painters has two tags. In 1925, a critic named Franz Roh came up with a nice phrase, magischer Realismus, which was later borrowed to refer to various writers, including Gabriel García Márquez and Salman Rushdie, whose work has absolutely nothing to do with Germany in the 1920s. Simultaneously a curator, Gustav Hartlaub, dubbed more or less the same sort of stuff Neue Sachlichkeit, or the new objectivity — another term which caught on.

On this evidence, however, neither name has much to do with the art it aimed to describe. What’s on show at Tate Modern is not magical, realistic, objective nor was it particularly new even 90 years ago. If pressed for common factors I’d go for caricature, satire and over-the-top horror. Furthermore, some of the works in the show are startlingly bad, and many distinctly second-rate (but that’s a separate question).

This display is culled mainly from one source, the George Economou Collection, with the rest from the Tate’s own cellars, which explains the deficiencies. Arranging an exhibition in that way restricts the choice. No doubt that is the reason why there is only one painting, ‘Anna’ (1942), by Max Beckmann, for example — who was one of the truly gifted artists of the era — not one that shows him anywhere near his best (nor is it from the Weimar years, which suggests there was trouble finding a suitable Beckmann).

On the other, there are four by Albert Birkle, a fairly obscure painter with whom the Tate seems strangely obsessed. There are more of his efforts over at Tate Britain in the Aftermath exhibition. And I suppose his work does have a certain fascination. It’s hard to think of a picture so thoroughly, almost interestingly, awful as his ‘Crucifixion’ (1921). It’s lurid, derivative, mawkish, embarrassing, flamboyant and boring all at the same time — quite a tricky combination to pull off.

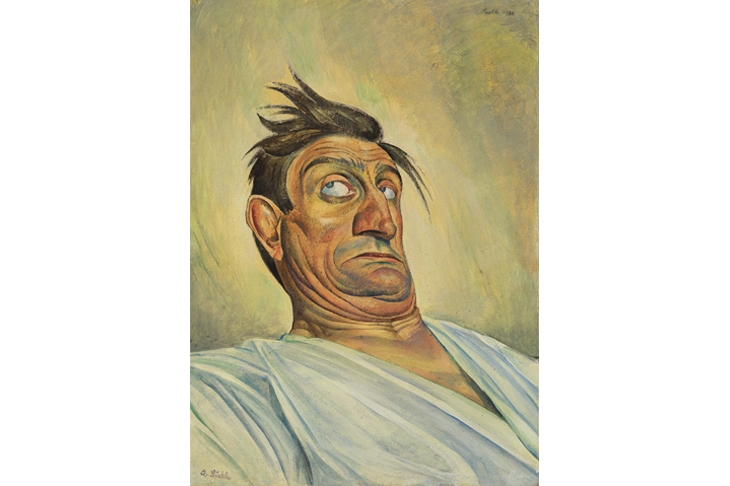

To be fair, his portrait of ‘The Acrobat Schulz V’ (1921) pulling a funny face has its attraction. The general effect and approach put me in mind of Birkle’s British contemporary, Donald McGill, once famous for his seaside postcards. George Orwell, a fan of McGill’s work, came up with the category of ‘good bad books’ to describe certain novels.

‘The Acrobat Schulz’ perhaps belongs in the good-bad pigeonhole. Whereas Birkle’s ‘Crucifixion’, along with his ‘Hermit’, and other works in the room devoted to religious imagery in the Weimar years, such as Herbert Gurschner’s ‘Annunciation’ (1929-30), can only be filed under bad-bad. On the other hand, typically for this show, there’s one terrific painting in the same gallery: Lovis Corinth’s ‘Magdalen with Pearls in her Hair’ (1919) from the Tate’s own collection. It’s an ageing nude, a variation on a venerable theme — the vanitas or memento mori.

Like Birkle’s ‘Crucifixion’, which is derived from Grünewald, this is quite a traditional picture. The difference is that Corinth — though he too was capable of lurches into a realm of extreme bad taste — was a master of luxuriously thick, impassioned brushstrokes. He could really paint.

What Otto Dix and George Grosz were doing was close to cartooning — which isn’t a criticism since the same could be said of a great artist such as Daumier. Grosz’s watercolour, ‘A Married Couple’ (1930) is a caricature much in the Daumier mode (with a touch of Giles of the Daily Express). Put that in the good-good pile.

Dix, of whose work there is a plethora in this show and also Aftermath, was more erratic. He had a tendency to go much too far. His watercolour ‘Lustmord’ (Sex Murder) from 1922, the killer’s tongue lolling out, is silly as well as nasty (and visually a bit of a mess). But Dix could produce a powerful mixture of the violent and the grotesque — especially when restricted to line alone, as he was in his series of etchings of circus performers from 1922. The baleful, whip-wielding female Tamer, in tights and boots with a low-cut top, could be an illustration for Christopher Isherwood’s novel Mr Norris Changes Trains or the musical Cabaret. Mentioning those is a reminder that this was an epoch that has exerted lasting fascination.

Weimar Germany produced its fair share of marvellous art. Unfortunately there isn’t enough of it in this exhibition, and far too many also-rans. As a result it succeeds in suggesting that this era of social upheaval, cultural energy and political turmoil was really rather dull.

Comments