Wow, can I just begin by saying how incredibly excited I am to be given this opportunity to write about such an awesomely exciting subject. Don’t worry, this isn’t the start of some interminable Oscars-worthy speech. In truth, I’m not remotely ‘excited’ at the prospect of writing this article about the overuse of the word ‘exciting’. That’s because I’m an adult and adults tend to temper their enthusiasm with cold, hard reality.

The last time I felt genuine excitement, as in jumping around the room wild-eyed and whooping, was as a child when I awoke to find one of my dad’s old socks stuffed with toys draped over the end of my bed. For children, everything is exciting because everything is new and filled with possibilities, even an old sock. Grown-ups, on the other hand, are beset by disappointment, cynicism and doubt, making it hard to muster anything more than mild bemusement.

As with so many hyperbolic, infantilising words – see also ‘wow’ and ‘awesome’ – exhibiting one’s ‘excitement’ has become the default response to anything even mildly diverting

Don’t get me wrong, I’m pleased to be writing this piece because writing gives me a certain amount of pleasure: pleasure being excitement’s cooler, more mature cousin. As with so many hyperbolic, worn-out words – see also ‘wow’ and ‘awesome’ – exhibiting one’s ‘excitement’ has become the default response to anything even mildly diverting. And if you refuse to go along with other people’s babyish exuberance you are seen as a grumpy old git.

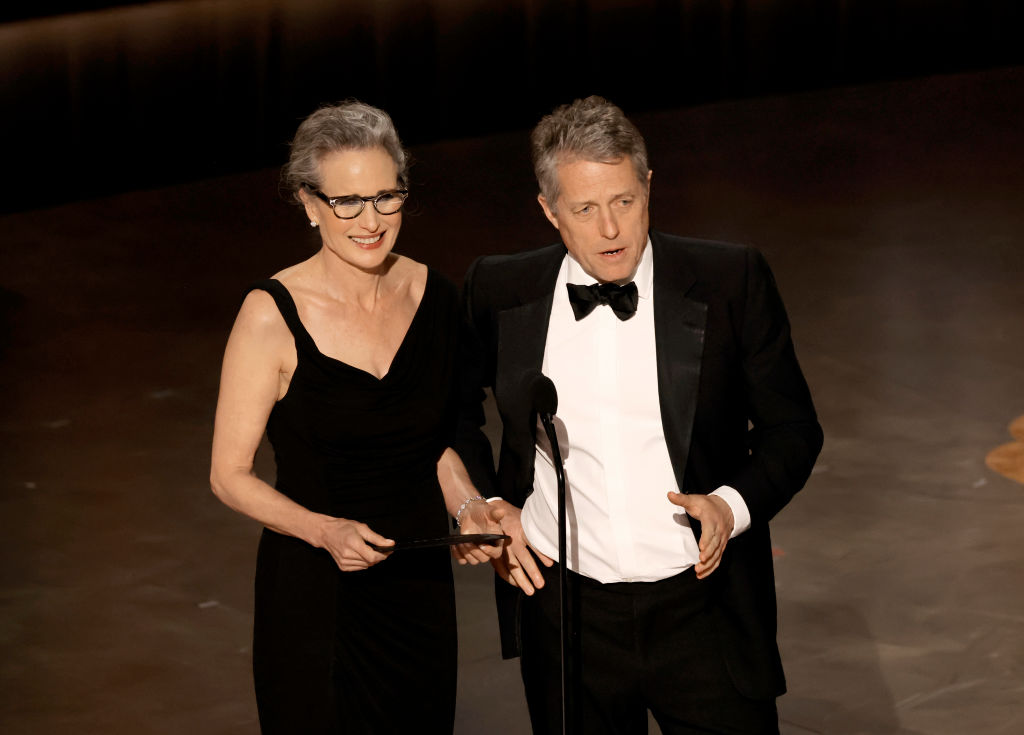

Look at the reaction to Hugh Grant’s perfectly reasonable response to that grinning, overdressed kidult Ashley Graham after she demanded to know what our Hugh was ‘most excited to see’ at the Oscars last week. ‘To see?’ ‘Yeah… are you excited to see anyone win…?’ ‘Erm, no, no one in particular.’ Afterwards, critics accused Grant of being ‘rude’ and ‘grumpy’ in the interview. But the fact that an honest retort to an inane question can elicit such consternation shows how susceptible we are to comforting delusion.

Of course, Graham wasn’t really interested in Grant excitement levels. As a performing monkey, his job was merely to mirror her phoney enthusiasm for the purposes of making an anachronistic event seem more exciting. Later in the conversation, when Graham asked about how much ‘fun’ the ‘amazing’ movie Glass Onion was and Grant said he was only in it ‘for about three seconds’, an increasingly desperate Graham pressed: ‘…but still, you showed up and had fun, right?’ ‘Err, almost,’ replied a cowering Hugh.

In order to justify inflated budgets, movie-making and the ceremonies that follow must be seen to be exciting ‘events’. But as any film actor and awards attendee will tell you, both occasions are characterised by boredom and repetitiveness.

Grant isn’t the only celebrity to expose the vacuousness of our media drones. Asked in 2019 whether he was as ‘excited’ as his hyperventilating host about being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, the perpetually dour Robert Smith of the Cure replied: ‘By the sounds of it, no.’

This infantile obsession with everything having to be ‘fun’ and ‘exciting’ plagues our culture. Even the most modest creative endeavour must now contain a sugar frosting of excitement to provide a ‘buzz’. Publishers drone on about how excited they are to have landed a ‘thrilling’ new book about dry stone walling in medieval Staffordshire. And I’ve lost count of the amount of times colleagues have boasted about their ‘exciting’ new projects.

Read any press release from a forthcoming restaurant, album or pop-up and the blurb will emphasise how excited everyone is to be involved with the new venture. But are they really jumping up and down, or merely just a bit pleased to have finally brought their product to market? For anyone outside PR’s world of perpetually puppyish enthusiasm, any mention of excitement tends to elicit a more weary response. Nothing is ever as exciting as they say. We live in a Tinkerbell world of enforced make-believe where a sexed-up, dumbed-down version of reality has been deliberately engineered to titillate and manipulate our emotions.

Almost two decades ago, the brilliant journalist Michael Bywater discussed the infantilisation of western civilisation in his book Big Babies. ‘Day by day,’ he wrote, ‘we grow more and more focused on the quick fix, the ticking-off, the expedient lie, the jingle, the spin, the catchy slogan, the obsession with safety, the horror of risk, the terror of complexity, the preoccupation with surface, the apportioning of blame, instant gratification… have you ever wondered what happened to grown-ups?’

It’s a question we grown-ups need to ask more than ever because right now we are trapped in a hellish playground filled with noisy, attention-seeking seven-year-olds ordering us about and telling us how to feel. When intelligent performers such as Hugh Grant and Robert Smith refuse to play along with the artifice, they do us all a favour by exposing the utter flimsiness of modern culture.

Comments