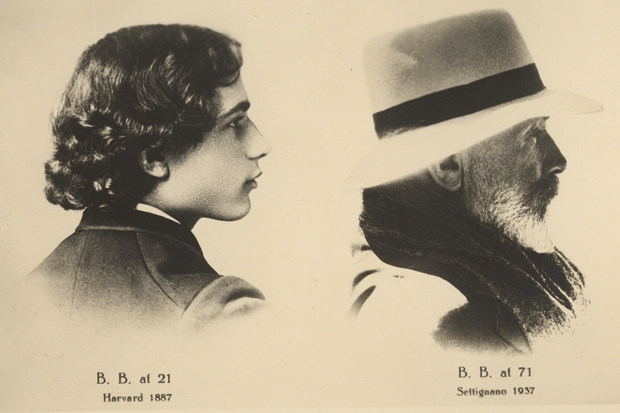

When the great Jewish-American art expert Bernard Berenson died in 1959, he had acquired the status of a sort of sage. He was the relic of a prewar culture that had vanished. He was an embodiment of the idea of connoisseurship that had at once given birth to a great boom in art collecting and yet that was, by the end of his life, being superseded. When Berenson embarked on the career that would see him widely accepted as the world’s foremost authority on Old Masters, the painters of the Italian Renaissance were barely regarded in the US. He died — at 94 — in the age of Andy Warhol.

The very span of his life gives his story resonance. Born Bernhard Valvrojenski, the son of a Jewish tin-peddler in the Pale of Settlement in Lithuania, and having grown up in Boston, he ended up living, as it seemed, the life of a wealthy Renaissance gentleman in Italy — though only narrowly did he and his art collection survive fascism and the second world war.

He was a prodigiously sociable man — a captivating conversationalist and hugely attractive to women. Both he and his wife Mary put it about like mad, though she didn’t always get her man. Of Geoffrey Scott, with whom Mary was at one point infatuated, Lytton Strachey wrote:

He remains a confirmed sodomite and she covers him with fur coats, editions of rare books and even bank notes, all of which he accepts without a word and without an erection.

Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde stroll in and out of this story, as do Bertrand Russell, Marcel Proust, Maxim Gorky, André Gide, Jean Cocteau and Cole Porter. And at the other end of things we meet Kenneth Clark, a Berenson disciple, as well as Hemingway, Steinbeck and the young Ray Bradbury.

This book appears as part of a big new series from Yale on ‘Jewish Lives’, and Berenson’s relationship to his Jewishness is accordingly very finely explored. Berenson himself more than once quoted Heinrich Heine’s saying: ‘A Jew, to be taken for silver, must be of gold.’ Berenson set about making himself of gold — reading ferociously and omnivorously, dazzling all with the brilliance of his talk, charming the first of many patrons and winning a place at Harvard. But 19th-century Boston may well have been the all-time snobbery capital of the universe. Anti-Semitism could be taken for granted. Berenson often had to nod at it.

His role in the art world was a double one. He shaped the way we look at Old Masters and he shaped the way we buy them. He was the author of exhaustive works of attribution and aesthetic theory, a disciple of Walter Pater who positively vibrated in front of paintings and made his attributions less on the basis of X-rays, pigment analysis or material science than his sense of a painter’s artistic personality as revealed through their characteristic aesthetic gestures. To start with, too, he was a great scrapper. An 1897 exhibition in London boasted 33 Titians and 18 Giorgiones. Berenson wrote a pamphlet saying it contained only one genuine Titian and one Giorgione drawing.

His writing, especially about painting, still has a wonderful freshness. Of Cosima Tura, he said: ‘His world is an anvil, his perception is a hammer, and nothing must muffle the sound of his stroke.’ Of Bacchiacca:

As he advanced, he grew colder and colder, until at last he becomes as leaden grey as a sky with a snow storm brooding over it. In his last pictures Bacchiacca is as delightful as a new graveyard on a dirty autumn day.

Returning to the great library he built, he talks of the ‘wild joys of getting back to [the books] … the cool silver shock of half-forgotten marvels.’

Yet at the same time, in order to sustain himself in the (considerable) style to which he aspired — his Florentine home, Il Tatti, was a magnificent villa in which he hosted grandee after grandee — he ducked and dived in the market, connecting dealers with collectors and providing the attributions and appreciation that underpinned the value of what they sold. His authority as a connoisseur was, in other words, thoroughly monetised.

Rachel Cohen’s unobtrusively and thoroughly well written short volume skilfully negotiates the contradictory sides of Berenson’s character — the aesthete and the huckster; the man who lived only for art and the man who very much liked to surround himself with the appurtenances of wealth. Reinvention was Berenson’s forte, and reinvention was, in some ways, exactly the business of the millionaire industrialists to whom he catered. Culture was something you could buy.

Cohen writes of J.P. Morgan that his

buying was on a gargantuan scale. He bought the contents of whole churches; he bought libraries; he bought private collections; he bought as a whale takes on seawater, sifting for plankton far down in the cavernous mouth.

When Isabella Stewart Gardner landed Titian’s ‘Rape of Europa’, she wrote to Berenson that it had only whetted her appetite for ‘a whacker … don’t you agree with me that my museum ought to have only a few, and all of them A No. 1s’.

The art trade, in those days, was bandit business:

Getting the picture you wanted was often a matter of having it cut down off the wall of a monastery and spirited out of the country before your rival could get there with his knives.

Did Berenson prostitute his expertise — ‘improving’ attributions for his own financial gain? The suspicion is there — though there are also many instances of his infuriating the dealers with whom he worked by refusing to play ball. The suspicion attaches to a stereotype. The role he had was of a part, says Cohen, with the roles often played by Jews:

The Sultan’s doctor, the emperor’s banker, the gentleman’s pawnbroker — the man whose knowledge of your intimate desires did not give him more power over you than your knowledge of his religion and credibility gave you over him.

Certainly, he didn’t always play a straight bat. He collected a commission from Isabella Stewart Gardner, for instance, letting out that he was directly in touch with a painting’s private owner — when in fact he was getting a dealer to fund the acquisition and collecting a commission from him as well. At one point she ‘nearly caught him doubling the price for a Raphael’. He was highly secretive about his long partnership with the dealer Joseph Duveen. In this context his vaunting of devotion to art as a way of resisting commercialism looks like so much PR blather. To Gardner, he wrote fawningly (of the fantasy of retreat from the vulgar braying of the world into artistic contemplation): ‘You are the only person in the world who could really live it.’

Yet he really seems to have felt the contradiction. In a late memoir, he wrote of having taken ‘a wrong turn’: the art business, he said,

took up what creative talent there was in me, with the result that this trade made my reputation and the rest of me scarcely counted. The spiritual loss was great, and in consequence I have never regarded myself as other than a failure.

Comments