Upbeat or downbeat? I asked last month whether the mood where you live is energised by enterprise or demoralised by public-sector retreat — or both. Replies poured in while the news mostly got worse. Governor Carney warned that ‘the UK cannot help but be affected by an unforgiving global environment and sustained financial market turbulence’ as shares took another dive. BP and Shell announced profit falls and job cuts. The Brexit debate took off, but the migrant benefits row overwhelmed any sensible discussion of economic pros and cons, on which voters must so far be utterly confused.

Then again, it wasn’t all bad: like-for-like retail sales surged by 2.6 per cent last month; domestic gas suppliers cut prices by 5 per cent and a new Shetland gas field came on stream that could fuel two million homes.

This mixed picture was reflected in your reports — and well summed up by a medical man: ‘My private patients generally tell me business is going well, but many I meet in the NHS seem to be finding times hard.’

It seems that if where you live is anchored by private-sector success, you’re much more likely to be on the cheerful side of the divide. Solihull, thanks to Jaguar Land Rover, is ‘quietly prosperous, resolutely comfortable, untrendy and obscure’, while nearby Kenilworth sees ‘signs of resurgence of the corner shop’. Along the M4 corridor, Reading with its business parks is ‘relatively buoyant’; Swindon benefits from Honda and Nationwide even if ‘our local authority struggles to keep the streets lit’; Tisbury is ‘an oasis of feelgood’ with a thriving high street and ‘a garage where they fill the tank for you and check your tyres just like old times’.

Up in the smoke, a Southwark resident enjoys the borough’s rising-affluent hipster tone, while complaining of ‘litter, incompetence of local bureaucrats, constant roadworks and an inability to get an appointment with your preferred doctor for up to four weeks’. But the further away from London, the more my many correspondents describe a recovery that never happened…

It’s that north-south divide

In north-eastern England, higher job numbers are ‘a veneer of hope that masks a bleaker picture’ of low wages and little to spend after bills have gone out. An IT contractor from Sunderland tells me that he has ‘long since given up on finding work in Tyne and Wear… All I can do is take time out to teach myself newer skills, and move further afield.’ Over the border in Kelso, local commerce is blighted by ‘Sainsbury’s glowering menacingly from the hill above the town and treating its customers with a strange mixture of contrived goodwill and profit-driven contempt; we go up there only to find what we cannot find in Lidl.’

Further north still, Aberdeen — devastated by the oil-price collapse — is ‘dying on its feet’, while right across Scotland ‘people in all walks of life are talking about moving businesses and families south’ to escape the SNP’s ‘managed destruction’ of the economy and the ‘desperate’ state of the Scottish NHS. Finally from Northern Ireland: ‘The chill winds can still be felt on every high street, where traders battle high rates and dwindling footfall. Charity shops are everywhere. Why so dire? The problem is that the banks remain crippled…’

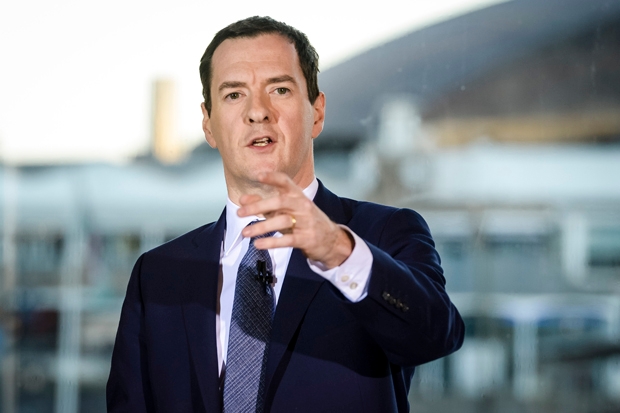

Make of this précis what you will: no one ever claimed Spectator readers form a representative sample. But if George Osborne would like the full text of your eloquent responses as he works on his Budget for next month, I’ll be happy to oblige. He might conclude, for example, that his long-overdue review of business rates should clearly favour smaller firms over very large ones, and the struggling provinces over the rich metropolis; and that his Living Wage has yet to make any impact at all on the socially corrosive income inequalities that are a residue of the long recession.

He might conclude too that the comfortably-off middle classes do not believe further shrinkage of public services will boost general prosperity or do anything other than damage their own local quality of life; in short, even his own people probably now think cuts have gone far enough.

Banking’s poet-statesman

I last spoke to former Lloyds Bank chairman Sir Jeremy Morse, who died last week aged 87, at a tea party on the lawn of All Souls, the Oxford college where he became a fellow as a young classical scholar. It was a scene that could only have been improved by the arrival (perhaps to arrest me as an imposter) of the cerebral, puzzle-solving, poetry-loving television detective who was modelled on Sir Jeremy and borrowed his surname. But it was also the perfect backdrop against which to remember this brainiest of bankers, whose clarity of mind translated into a strategy that took Lloyds to the top by focusing on low-risk high-street opportunities while shunning the dangerous glamour of global securities markets.

Unlike many of today’s City men, Sir Jeremy was also both moral and humane in his approach. Unfashionably, he believed it was ‘wrong for individuals to borrow’; but experience at the IMF in the 1970s, and in resolving the Latin American debt crisis a decade later, also taught him that there comes a time when the burden of borrowing is better forgiven: he once gave me a brisk lecture on Solon, the Greek poet-statesman whose debt relief measures helped save ancient Athens from economic paralysis.

My predecessor Christopher Fildes recalled seeing the gentle side of Morse at a centenary party for T.S. Eliot, who was working for Lloyds in Cornhill when he wrote The Waste Land. ‘Sir Jeremy began to read: “A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many/ I had not known death had undone so many…” He checked for a moment and continued, and I thought, hearing him, that there was something not quite familiar about his text. Was this a draft rediscovered in Lloyds’ archives? No — but Eliot’s words had moved Sir Jeremy to tears, so that he could not see through his glasses. He had finished the poem from memory.’

Comments