Why do painters represent things? There was a time when the answers seemed obvious. Art glorified power, earthly and divine, and provided moral exemplars of how to behave – in the case of sacred paintings – or how not to in the case of profane ones. When modernism threw all that into doubt, the picture frame remained. The question for modern artists was, what to put in it?

Fifteen years of non-representational painting prompted Guston to question its usefulness

For the first decade of his career, Philip Guston had an old-fashioned answer: the murals he painted in the style of Italian Renaissance frescoes in the US and Mexico during the 1930s promoted ideals of social justice. In 1931, when LAPD’s Red Squads destroyed the teenage Guston’s portable mural in support of the Scottsboro Boys – who were falsely sentenced to death for raping a white woman – he took it personally.

Growing up as a Jewish immigrant kid in Los Angeles in the 1920s – when the Ku Klux Klan led rallies, broke strikes and drove openly around town in full regalia – he had experienced racism at first hand. In a teenage drawing he portrayed Klansmen officiating at a crucifixion, and masked or hooded figures continued to people his early allegorical paintings. They disappeared from view in the 1950s after he joined the New York School of abstract expressionists, but 15 years of non-representational painting prompted him to question its usefulness. ‘What kind of man am I,’ he found himself asking, ‘going into a frustrated fury about everything, and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?’

Against the political backdrop of the late 1960s the ‘hoods’ returned to his work like acid reflux, an emblem of the human capacity for evil. It’s their presence in his later paintings that caused the two-year hold-up in Tate Modern’s current Guston retrospective while the participating galleries dithered over racial sensitivities in the wake of Black Lives Matter. How times change. When Guston first unveiled these images at New York’s Marlborough Gallery in 1970, it was their cartoon style that caused the outrage. ‘It’s as if De Chirico went to bed with a hangover and had a Krazy Kat dream about America falling apart,’ wrote the Village Voice’s John Perreault in the show’s only favourable review. He got the point.

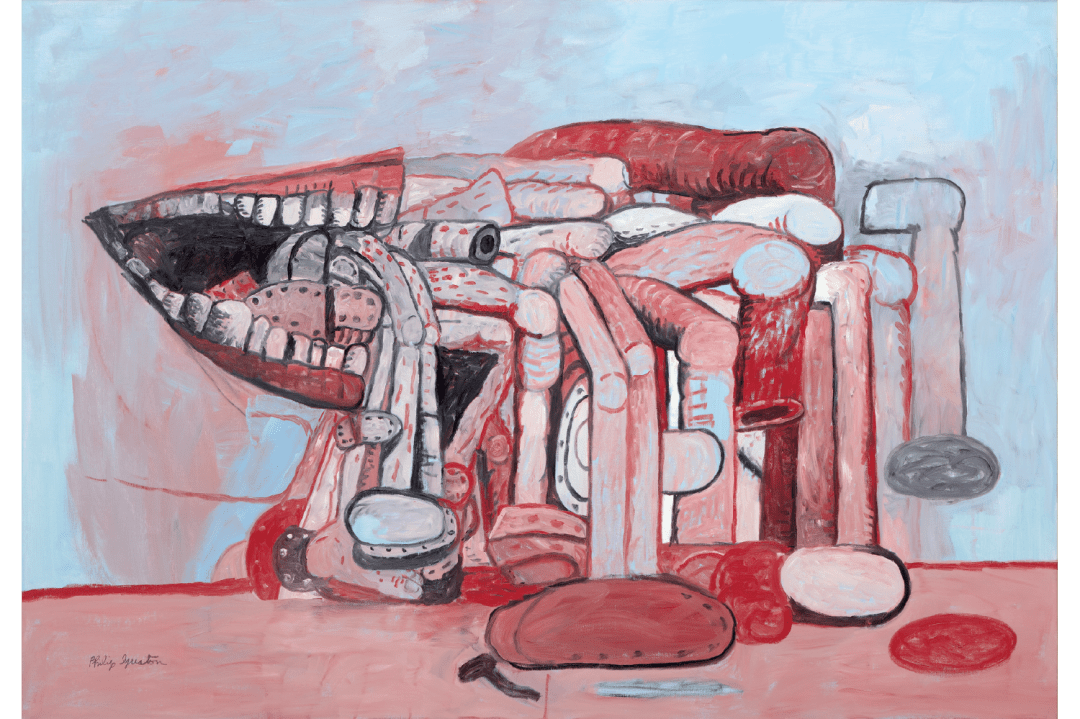

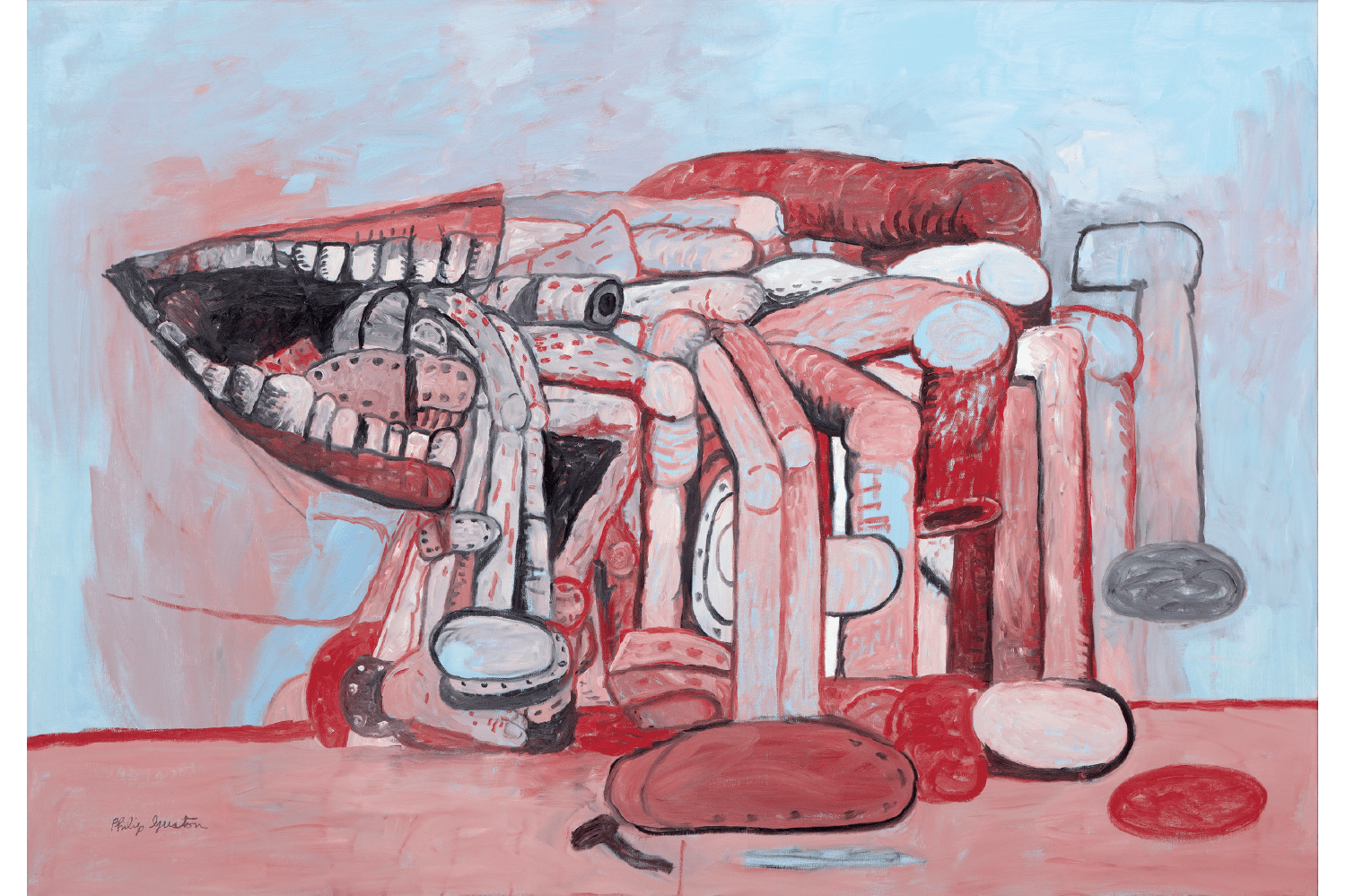

The palette was as much of a shock as the style. In the ‘Hoods’ gallery you could be on the set of Barbie: everything is pink and plasticky. In the rosy ambience of ‘The Studio’ (1969), a hooded Klansman sits at an easel, cigar in hand, painting a self-portrait of the complicit artist: ‘I perceive myself as being behind the hood,’ he said. In 1923 the ten-year-old Guston had found his father hanging in the garden shed and seven years later his brother Nat had died of gangrene after his legs were crushed in a car accident. The traumas left Guston with a legacy of survivor’s guilt. Ropes, legs and shoe soles haunt his later canvases like recurring nightmares. In ‘Painter’s Forms II’ (1978) dismembered legs spew like half-eaten spaghetti from a hood-shape lined with teeth like the mouth of a shark; in other paintings piles of shoes and legs recall photographs from the liberated concentration camps. ‘I really only love strangeness,’ he confessed. ‘But here is another pile-up of old shoes and rags, in a corner of a brick wall.’

His readiness to find meaning in stuff he called ‘crapola’ and elevate it to the status of art has made him a hero to a new generation of painters.

It’s no coincidence that feet and legs also loom large in the Serpentine’s new exhibition of Georg Baselitz, as Guston is one of his artistic idols. The show is the first to exhibit the original wooden maquettes for Baselitz’s better-known bronzes, though the diminutive hardly describes these massive sculptures hewn, hacked and scarified with chainsaws, axes and chisels from the single trunks of enormous trees. If Guston’s cartoon inspiration was Krazy Kat, Baselitz’s could be The Flintstones.

Unusually for this artist, the images are the right way up. In 1969 Baselitz hit on the idea of inverting images as a halfway house between figuration and abstraction, and he has been painting and hanging canvases upside-down ever since. But the upside-down thing doesn’t work with figurative sculpture: turn it on its head and it falls over. His sculptures stand on their clodhopping feet and their related drawings, not being arsy-versy, reveal what an expressive draughtsman he is.

If Guston’s cartoon inspiration was Krazy Kat, Baselitz’s could be the Flintstones

One image could be a lightning sketch of a model pacing a runway wearing something ridiculous, another suggests a seated nude on an office swivel chair. The movement carries through into three dimensions in the hula-hooping ‘Louise Fuller’ (2013). Deliberately crude but deceptively complex, several figures are circled with hoops of wood ingeniously fashioned from the same single trunk like giant wooden ring rattles carved by an axeman.

‘The trouble with recognisable art is that it excludes too much,’ said Guston; the trouble with unrecognisable art is that it includes too little. That is the dilemma of modernism which artists find their own ways to resolve.

Comments