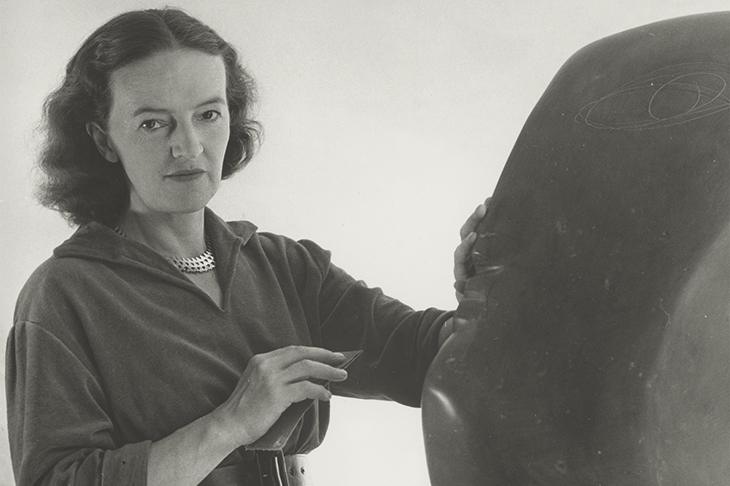

‘To see a world in a grain of sand’, to attain the mystical perception that Blake advocated, requires a concentrated, fertile imagination. Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), one of the leading and most popular British sculptors of the 20th century, fervently imagined that her works expressed cosmic grandeur and her own spiritual aspirations. In the foreword to this thoughtful and enjoyable biography, Ali Smith testifies that Hepworth was ‘fiercely intelligent’, while its author, Eleanor Clayton, candidly declares: ‘I write as a curator who loves the artist she presents, a fan writing of her hero.’ Her research shows how frequently the sculptures convey ‘concepts [Hepworth] considered universal and eternal’.

Clayton, eminently qualified as an expert on all aspects of Hepworth’s long and prolific career, is curator at the Hepworth Wakefield gallery, which will present a major retrospective from 21 May until 27 February. Wakefield, in Yorkshire’s West Riding, is where Hepworth was born, and Clayton has organised other exhibitions such as Hepworth in Yorkshire and A Greater Freedom: Hepworth 1965–75, co-founded the Hepworth Research Network with the universities of York and Huddersfield, and published widely on British modern art.

Hepworth had a comfortable, happy childhood and always cherished vivid memories of Yorkshire, explored with her father, a county surveyor and alderman, who encouraged her by enrolling her at Leeds school of art. She entered at 17, when Henry Moore, a Yorkshire coal miner’s son, had already been there a year. Having served in the army for the last two years of the first world war, he was 22 when they met. They had ‘a little affair’, Moore said, but he later more tactfully described their relationship as that of a brother and younger sister.

It seems probable, though uncertain, that Moore aesthetically dominated their early conversations. Anyway, after further education at the Royal College of Art in London they went separately to work as sculptors. The first products of their hammers and chisels were notably similar, his ‘Madonna and Child’, her ‘Mother and Child’. They both sculpted approximately biomorphic female figures, with small heads, elephantine legs, and curves in between perforated by immediately recognisable large, circular holes.

Hepworth went on to exhibit with another fellow sculptor, Paul Skeaping, in London galleries. In 1928 they toured Tuscany together, married in Florence and, back in England, she gave birth to a son, named after his father. As the marriage was breaking down, she turned her attention to Ben Nicholson, the distinguished abstract painter. In 1939, when war was imminent, he took Barbara and Paul to St Ives in Cornwall, where Hepworth would live, as an increasingly important artist, for the rest of her life.

In 1934, expecting another baby, she was surprised, on 3 October, to deliver triplets — Simon, Rachel and Sarah. Nicholson, too, was surprised; they had £20 in the bank. Two months later he found his own career and demanded a trip to Paris. From then on, he was often an absentee husband, usually residing in London. She wrote frequent, eloquent letters to him, expressing her affection for her family and complaining that domestic chores were exhausting her. She loved her four children, but loved her art even more. For professional and financial reasons, she felt she needed to sculpt every day.

Politically liberal, a ban-the-bomb activist, she was naturally drawn to friendship with Dag Hammarskjöld, the director-general of the United Nations. Having met him in New York, she engaged in a correspondence in which he professed his love of art and world peace and she her love of world peace and art. She presented him with a sculpture for his office. After his death in a plane crash on a mission to negotiate peace in the Congo, she speculatively developed an abstract, ‘Single Form’, in plaster, for casting in bronze. The design was similar to some of her previous works only much bigger, about 20ft high, with a giant hole near the top. In the hole’s rim she inscribed: ‘To the glory of God and in memory of Dag Hammarskjöld.’ The UN formally commissioned the work in 1962 and she ceremoniously installed it on the forecourt of its headquarters two years later.

There were tragedies. Hepworth’s first son, Paul, an RAF pilot, also died in a plane crash. Hepworth herself suffered a long-drawn-out, painful illness and diedin a fire in the apartment above her studio. In her will, she left the studio and garden as a museum to display her work. Administered by Tate St Ives, it attracts thousands of visitors every normal year.

The biography’s many excellent illustrations, aligned with relevant passages of text, have helped Clayton put together a comprehensive account of Barbara Hepworth’s talent and determination.

Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life is at the Hepworth Wakefield from 21 May–27 February 2022.

Comments