Easter and Passover coincided this year, so we’ve been in America visiting my in-laws. Four years ago, in the spirit of the holiday of liberation and exodus, we had all travelled to the Ukrainian village outside Lviv from which my father-in-law’s family emigrated. In just a few short generations during the 20th century, people there found themselves labouring under the Austro-Hungarian, Polish, Nazi and Soviet yokes. The disastrous human consequences are laid bare in Bernard Wasserstein’s poignant new history, A Small Town in Ukraine. Now Russian missiles intermittently rain down, partly enabled by sanctions busting and dirty money. When President Zelensky addressed the British parliament a couple of months ago, he drove past luxury flats overlooking our Ministry of Defence and reportedly owned by Putin’s former deputy prime minister. They are just the £11 million tip of a £6.7 billion iceberg of dodgy UK property. In the Lords this week, a cross-party coalition is trying to strengthen the Economic Crime bill and shut the ‘London laundromat’. Russia must compensate Ukraine for its illegal invasion. A good place to start would be converting frozen illicit assets into Ukrainian reparations.

My first visit to Washington was as a student at the height of the Iran-Contra affair. A friend got us into the Oval Office, and I particularly remember Ronald Reagan’s desk toy. As the Cold War reached its denouement, his small wooden spinning ‘decision maker’ was marked ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘maybe’ and ‘scram’. Amusing, but not totally reassuring. Now this Easter it’s my turn to show my daughter around. So it’s irritating to find Smithsonian museums still operating pandemic-era ticket restrictions discouraging spontaneous visits. Not so the Lincoln Memorial, with its open-to-all sculpture of craggy Uncle Abe, and marble inscriptions of his second inaugural speech and Gettysburg address. What he lacked in Instagrammable good looks he made up for in tweetable concision. But his sobering texts remind us that the Civil War began just 85 years after the founding of the republic. With the United States arguably as divided now as it was then, can the Union hold? On balance I think it can. For better or worse, conflict is intrinsic to America.

From DC we head to New York, avoiding airports for the much less chaotic train. In the margins of a board meeting I’m attending on the Upper East Side, I squeeze in a visit to the exquisite Neue Galerie, and its restituted Nazi-looted art. Ignore the hyperbole praising its patron, and ignore the overhyped medieval armour (have they not seen Glasgow’s Burrell Collection?). Instead lose yourself in the anchor piece of the museum – Gustav Klimt’s sensuously gilded portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer.

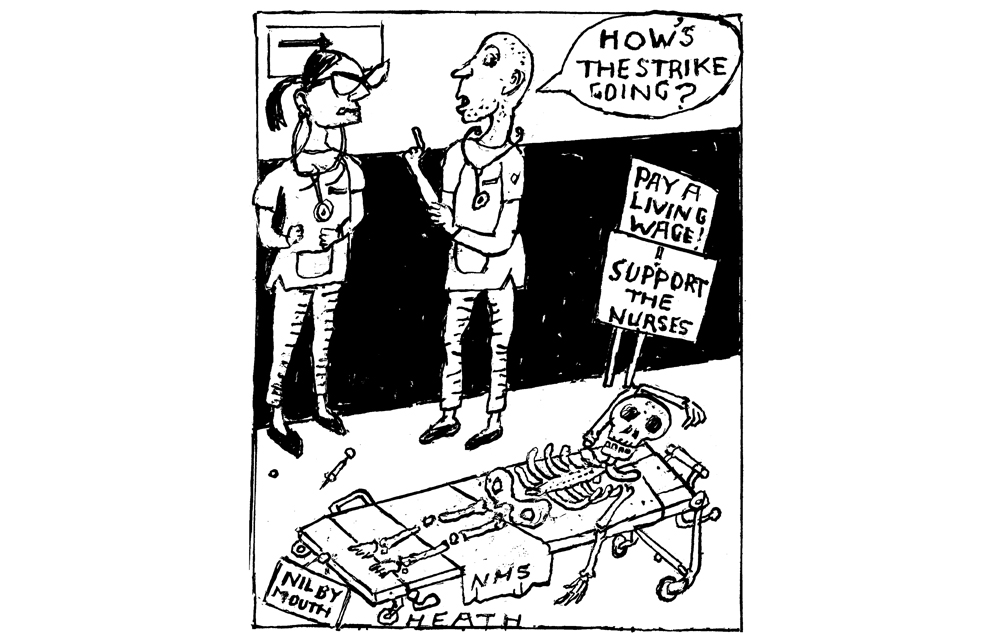

Now back in London, and it’s clear the health department’s industrial relations strategy isn’t going to plan. Having tried to tough it out, their attention switched to the Royal College of Nursing, hoping other union dominoes would then fall. But the RCN is still reeling from a CBI-style sex scandal, and its members have ignored their own leaders and narrowly voted no to the latest pay offer. Paradoxically the government’s wider NHS pay deal now hinges on the pragmatism of Labour-affiliated unions such as Unison, which has voted in favour. Matters are even messier when it comes to the junior doctors. Theirs is a rear-view-mirror claim for pay restoration after a decade or more of real-terms erosion. So unlike the nurses, improvements in the forward inflation outlook make less difference to their negotiating stance. As with striking doctors in many other countries, medical dissatisfaction also has deeper causes. These include legitimate concerns about pandemic burnout, staffing levels, career flexibility, and – thanks partly to the European Court of Justice – the loss of the ‘firm’ apprenticeship model in place of shift working.

Could the current lose-lose standoff have been avoided? By last autumn it was obvious that inflation was far higher than assumed by the independent NHS review bodies, so their original recommendations wouldn’t stick. At that point they could have been asked, exceptionally, to make an improved 18-month pay recommendation. That might have drawn the sting, while preserving their legitimacy. Had it been coupled with the government’s long-awaited NHS workforce plan to expand and reform training, frontline staff might have seen light at the end of tunnel. Now if further strikes drag on, at the very least waiting lists will worsen. The nuclear option of withdrawing cover for emergency services and urgent cancer care would be unconscionable.

To end on a more positive note, at 1 a.m. on Tuesday I find myself with other members of the Armed Forces Parliamentary Scheme outside Wellington Barracks opposite Buckingham Palace. The Household Cavalry have invited us to observe their mounted rehearsal for the coronation, under cloak of darkness. The martial precision and logistical complexity of ‘Operation Golden Orb’ is extraordinary. That excellence shouldn’t, however, obscure the fact that at the time of the last coronation in 1953, our armed forces were more than four times larger than today. With the world as it is, we’re going to have to grow them once again.

Comments