Today, the German city of Jena, 150 miles south-west of Berlin, is the world centre of the optical and precision industry; but in the 1790s it spawned an even more marketable commodity. It was then a small medieval town on the banks of the river Saale with crumbling walls, 800 half-timbered houses, a market square and an unruly university. Here, in the philosophy department, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a young professor inspired by Immanuel Kant and the French Revolution, proclaimed from the pulpit his theory of the ‘Ich’. ‘A person,’ he roared, ‘should be self-determined.’ In an age of absolute power and the divine right of kings, the idea of free will was an incendiary device and Fichte freewheeled his way through each lecture. ‘Attend to yourself,’ he instructed his mesmerised followers; ‘turn your eye away from all that surrounds you and in towards your own inner self.’ Fichte’s lectures, says Andrea Wulf in her engrossing new book, re-centred the way we understand the world. It’s little wonder that intellectuals flocked to Jena.

Magnificent Rebels is a group biography about the decade between 1794 and 1804 when a cohort of writers, philosophers and translators, ignited by the cries of liberty, equality and fraternity coming from Paris, turned Jena into a hub of revolutionary thinking. The book is also a beginner’s guide to German idealism. It’s no mean feat to explain such hefty theories in layman’s terms, and Wulf does so without, as Byron said of Coleridge, needing to explain her explanation.

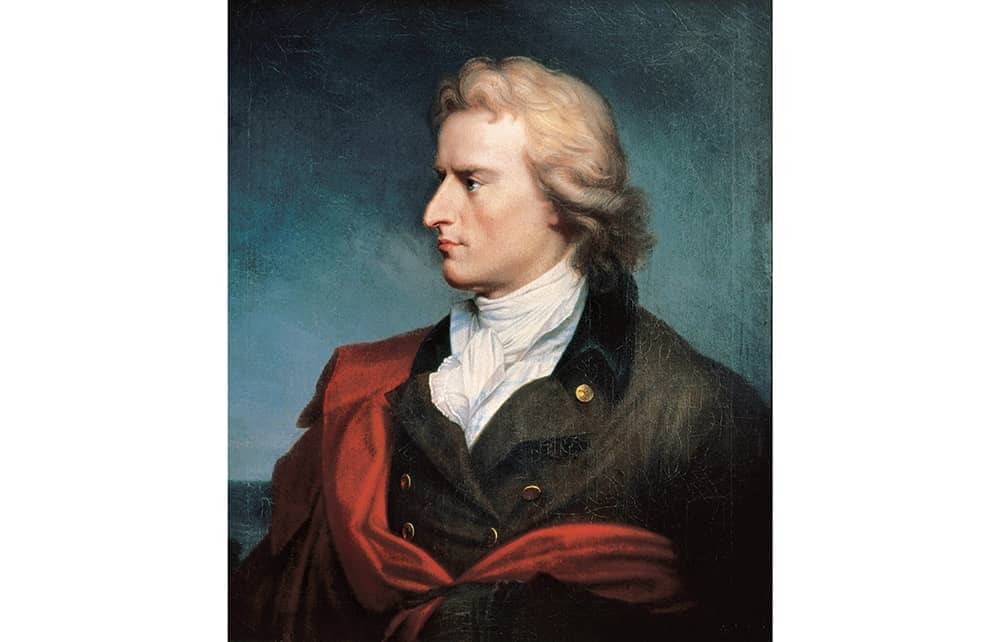

The grandfather of what she calls ‘the Jena set’ was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose 1774 novel The Sorrows of Young Werther turned suicide into an art, or group-think. Goethe, who lived with his mistress and son in nearby Weimar, was first invited to Jena by the playwright Friedrich Schiller, who began lecturing at the university in 1789. Their friendship initiated what Goethe described as a ‘new era’ in his writing. The effect of Jena turned Goethe into a ‘demi-god’ for a new generation of readers.

Everyone in Jena hated everyone else and did all they could to stymie each other’s careers with bad reviews

The town muse was Caroline Böhmer-Schlegel-Schelling, a ‘politico-erotic’ fire-ball who, together with her young daughter Auguste, had spent six months in prison in Königstein in 1793. Caroline and her second husband, the poet, critic and translator August Wilhelm Schlegel, came to Jena in 1796, where the couple translated, for the first time, Shakespeare into German verse. Their translations are still the standard edition in Germany. It was August Wilhelm who coined the term ‘Romantic’ to describe the new sensibility whose impact was also being felt in the English Lake District. ‘Speak nothing but German,’ Coleridge (unsuccessfully) counselled Wordsworth: ‘Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’

August Wilhelm was joined by his younger brother, the writer Friedrich Schlegel, who was himself in love with Caroline. (‘One look is all it takes’, Friedrich said of her.) Friedrich brought along his best friend, the poet and mining inspector Friedrich von Hardenberg, who used the pen name Novalis. ‘My whole self,’ said Novalis, ‘is a system of fragments’, and together with Schlegel, he invented the Romantic fragment. Schiller and the Schlegels were then joined by the young philosopher Friedrich Schelling, who taught at the university between 1798 and 1803. The similarity of names makes this a difficult book to follow after a glass or two of wine, but keeping up with the Jena set is challenging in other ways too.

‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,’ said Wordsworth of the French Revolution, ‘but to be young was very heaven.’ Jena, now the centre of this heaven, was actually very hell. Caroline Schlegel described it as a ‘den of murderers’, and she wasn’t far wrong. Jena reduced the whole world to a town which could be crossed in ten minutes flat; no one read the newspapers and nothing was discussed beyond gossip and the new philosophy. Everyone hated everyone else and did all they could to stymie each other’s careers with bad reviews. One of Schiller’s poems, wrote Friedrich Schlegel, was so bad it was best read backwards.

Schiller and the Schlegels were thereafter mortal enemies, as were Schiller and Alexander von Humboldt, Schiller and Fichte, and Friedrich Schlegel and Friedrich Schelling. While Schiller, who never left his house, hated everyone except Goethe, Fichte was not only hated by all his colleagues but those students who didn’t buy into his philosophy threw bricks through his windows. These attacks – which took place night after night for five months and once nearly killed his father-in-law – must have been, said Goethe, ‘a most disagreeable way’ for Fichte ‘to have the existence of a non-Ich proven to him’.

Everyone equally hated Friedrich Schlegel. One look, apparently, was all it took: ‘People prefer to observe me from a distance,’ he said, ‘like a rare and dangerous beast.’ They similarly hated his wife Dorothea, who in turn hated Caroline Schlegel, who hated Schiller’s wife Charlotte. ‘The minute she’s out of the house,’ Caroline said of Charlotte, ‘you should fire up two pounds of incense to purify the air.’ When Friedrich Schlegel’s friend, the poet and translator Ludwig Tieck, moved to Jena in 1799, everyone hated Frau Tieck too: ‘Oh, that wife! That wife!’, Friedrich complained to Caroline Schlegel.

Caroline is the heroine of the story, not least because she internalised the Ich-philosophy which, Fichte stressed, applied only to men. A woman, Fichte insisted, had to submit her own Ich to that of her husband. Caroline, accordingly, changed husbands three times, divorcing August Wilhelm in 1803 in order to marry Friedrich Schelling, who was, she said, ‘the kind of man who bursts through barriers’.

One reason the Jena set idealised the mind is because their bodies were so imperfect. The illnesses they suffered – gout, tapeworm, ‘nervous fevers’, infections, coughs and tumours – were treated by the local quack Dr Stark with the usual leeches, poultices, enemas and blood-lettings. When Caroline was given a mustard plaster made of horseradish to cure her sleeplessness, it inflamed her leg and led to cramps. Her daughter Auguste died after being prescribed laxatives, of all things, to stop her dysentery. Schiller, who experienced such ill health in Jena that his major organs were destroyed, was discovered after his death to have had a ‘hard, petrified sponge’ instead of a heart, which made Friedrich Schlegel laugh. One of the book’s finest chapters is an account of Novalis’s 14-year-old fiancée undergoing an operation on her liver without anaesthetic. The doctor who killed her was, of course, the wretched Stark.

Magnificent Rebels is a magnificent book: a revelation which could easily become an obsession. Wulf does not draw the analogy, but Jena was a prototype of Silicon Valley, a factory in which a handful of geeks open up our skulls and rewire our brains. The Jena set invented the self, and in doing so invented us all; we now think with their thoughts and feel with their emotions. They paved the way for Walt Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’, Henry David Thoreau’s ‘Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself’, Freudian psychoanalysis and Hitler’s fascism, the ‘Ich’ of a nation. Jena was the birthplace of self-consciousness, self-obsession, selfishness and selfies – the whole business of me, me, me and me too.

Comments