My first night in Turin, I thought of all the things I could be doing in this north Italian city, if I was there strictly for tourism. I could have gone to the Cathedral and seen a digital display of the Turin Shroud (the real thing is hidden away from prying eyes), or visited the National Museum of Cinema, housed at the Mole Antonelliana, that magnificent, spired tower – a failed synagogue – in the city centre. I could have drunk Barolo wine or Vermouth (another Turinese product), striking up conversations with the local Piedmontese to find out if they really are as cold, correct and altogether un-Italian as other regions in Italy often claim them they are.

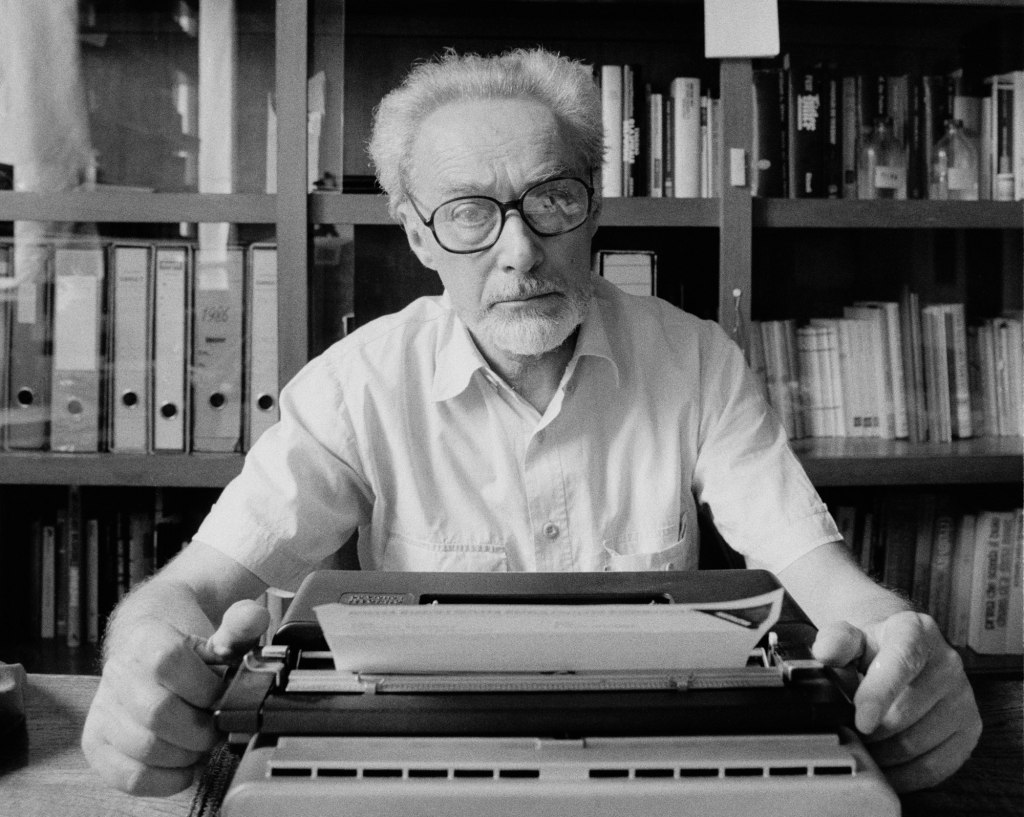

But I was in Turin strictly on the trail of Primo Levi, the scientist, writer and concentration camp survivor – who hailed from this city and, till his death 38 years ago today, spent nearly all his life here, juggling the twin demands of chemistry and literature. In 1947, two years after the end of the war, Levi – a highly assimilated Turinese Jew – had published Se questo è un uomo (If this is a man), a harrowing account of his time at Auschwitz. It went on to be one of the foundational texts – perhaps the foundational text – on surviving the Holocaust.

Later in life, there were other works from him on the same subject: The Truce and The Drowned and the Saved among them, all written in Levi’s palpably coolheaded, questing, humane tone of voice. They were books I knew had formed my view of the world, and I’d long promised myself a visit to the city which had formed Primo Levi.

Any visit to Levi’s Turin starts and finishes with his apartment building at Corso Re Umberto 75. Located in La Crocetta, a smart, central neighbourhood of robust-looking apartment blocks, the flat has been in Levi’s family since 1909 (his surname is still listed, affectingly, on the brass-plated doorbell). Re Umberto 75 was where Primo Levi was born in 1919, to an engineer father and a literature-loving mother, and where he died 67 years later, falling three floors down the stairwell – on 11 April, 1987 – in what the coroner (and many of Levi’s associates) deemed an act of suicide.

Though experts at Turin’s National Centre for Primo Levi Studies – located on Via Carmine – warn strongly against simple explanations for his death, you don’t have to hunt for reasons.

Levi, said his friends, was visibly depressed in his final year by – among other things – a prostate operation, the worsening health of his mother and mother-in-law, his declining (as he saw it) literary skills, and a growing tendency among ‘revisionists’ to play down, four decades on, the enormity of the Holocaust. There are also genetic factors to consider – his grandfather had killed himself almost exactly the same way a century before, and from his adolescence onwards Levi – usually the smallest, puniest and most sexually backward pupil in his class – spoke of suicidal thoughts.

Then there was his statement, shortly before his death, that he’d lived a ‘completely useless life’ – barely believable given the rigorous way he used it, year on year, to bear witness to some of the worst crimes in history.

Viewed in retrospect, Levi’s life seems as resolved and undeviating as one of Turin’s arrow-straight avenues. Apart from a year as prisoner at Auschwitz (and another spent working in Milan), he lived in the same apartment his entire life, was employed for three decades at the SIVA paint factory (rising to become general manager there) and remained married to the same woman for 40 years. Such stability allowed him to pursue his passions, as well as a literary career. He loved the gridded streets of his birthplace (so untypical of Italy), games of chess, Mendeleev’s Periodic Table, the order chemistry imposed on a dauntingly random world.

I didn’t make it to Levi’s paint factory (it’s slightly out of town), but in central Turin plenty of other places remain. At Via Massena 39 is the ‘Felice Rignon’ primary school he attended from the age of six and where one teacher, Emilia Glauda, taught him early on the importance, in the words of biographer Ian Thomson, ‘of concision and due proportion in prose.’ At his secondary school, the M. D’Azeglio Gymnasium (still going strong), the point was driven home by his Italian teacher Azelia Arici, who, Thomson tells us, warned sternly against the ‘vacant or woolly’ kind of writing she called ‘vapourings.’ If Levi’s later books are anything to go by, they were lessons he never forgot.

Nor was his life only study. On Piazza Vittorio Veneto, the slightly run down Café Elena with its dark wood and marble tabletops, where Levi used to drink Bicerin (Turin’s signature drink of espresso, molten chocolate and whipped cream) with friend and fellow chemistry student Mario Piacenza, is still doing business. Nearby is the Cinema ‘Ideal’, opened between the wars, where, in lighter moments, he went to watch Fred Astaire films. All this, of course, took place against a background of rising anti-Semitism under Mussolini, as the Italian dictator, in power since 1922, sought approval and support from Adolf Hitler.

On Via Po is the splendid, cupolaed grey synagogue, attacked by arsonists in October 1941 (Levi was one of the local Jews subsequently deputed to stand guard outside it). The Jewish School to which many – like Levi’s sister – flocked, after Jews were banned from attending Italian state schools, is still flourishing on the nearby Via Sant’Anselmo. It’s named after the historian and partisan Emanuele Artom, who (before torture and execution by the Nazis) ran a wartime salon for Jewish intellectuals at Via Sacchi 58, just down the road. Anyone wishing to see the Chemistry Institute where Levi studied can find it just above the riverside Valentino Park, where during the war a starving population grew maize and potatoes. Levi was a star student there – one of only two Chemistry undergraduates awarded summa cum laude in the previous quarter century – but the words ‘of the Jewish race’ were also stamped on his diploma, and he was eligible neither for fellowship in his department nor a legal job outside it.

To read about Turin in the thirties and war years is to see the tragic disillusionment of the city’s Jewish population, who believed – in a modern, Christian country with a Catholic Pope, where many Jews, rigorously assimilated, supported Mussolini – that the horrors in Germany couldn’t possibly happen there. But after years of growing persecution and disenfranchisement, a final decree on 1 December 1943 came as a death blow, ordaining that Italy’s Jews, ‘no matter their nationality’, were to be arrested and their property confiscated by the state. Levi, joining a ragtag band of partisans, was captured in 1944. As he waited outside Turin to be moved to a transit camp and then to Auschwitz, he could see in the distance, he said, the spire of the Mole Antonelliana: ‘That was the moment I said goodbye to my past forever.’ He’d return after the war for another four decades – but to a new Italy, a different Turin, and he himself, inevitably, a man branded forever by the camps.

This is clear enough from his grave, which I found on my last day in Turin – in a far corner of the city’s ‘Monumental Cemetery’, on Corso Novara. Though, traditionally, there was a special area reserved for suicides, the Chief Rabbi refused to condemn Levi to it. The writer’s death, he declared humanely, was – in view of his Auschwitz internment – more an act of ‘delayed homicide’ than one of self-harm.

In a city one of whose maxims is ‘Esageroma nen’, (‘Let’s not exaggerate’) Levi’s gravestone, you’re not surprised to see, is a plain grey marble slab, on which is written the author’s name, his dates (1919-1987) and between them a chiselled ‘174517’ – his prisoner number at Auschwitz, which remained tattooed on his arm ever after.

Primo Levi, the simplicity of that headstone suggests, may have been a faithful, even typical citizen of Turin, which never relaxed its claim on him or let him go. But, in death as in life, the experience of the Holocaust – a terrible second birth, perhaps, for Levi – had marked him just as deeply, and formed the writer whose quiet genius seems still to preside over his beautiful, complex city.

Comments