It sometimes rains in Cookham. It rained all day when I visited the Stanley Spencer Gallery to see the exhibition Love, Art, Loss: The Wives of Stanley Spencer. But it rarely rained for Spencer, or at least never in his pictures of his hallowed birthplace, where even when skies are grey the red brick of the houses is warmed by the eternal summer sun of childhood.

Not in the winter of 1937, though. That winter saw the 46-year-old artist rattling around his seven-bed family home, divorced from first wife Hilda Carline and separated from second wife Patricia Preece, painting pictures of grotesquely ill-matched couples who seemed unaccountably happier than him. He had married Patricia the previous May, four days after divorcing Hilda, then spent the wedding night with Hilda in Cookham while Patricia went on ahead with her friend Dorothy Hepworth to their Cornish honeymoon destination. After that Patricia permanently withdrew her favours, while Hilda refused to become his mistress.

Stanley married Patricia four days after divorcing Hilda, then spent the wedding night with Hilda

Lost already? Spencer’s midlife crisis was an omnishambles, but the signs had been there long before. Any 34-year-old male virgin who enters into marriage after half a dozen proposals and one cancelled wedding is going to hit trouble down the line. It was the sight of Hilda on the kitchen table having her wedding dress fitted that first gave Stanley cold feet in 1922; at the eventual wedding three years later Hilda wore an ordinary brown velvet suit. But Stanley felt no compunction at illustrating the wedding-dress scene for a Chatto & Windus Almanack in 1926. All memories, for Stanley, were by definition golden; for Hilda, one imagines, not so much.

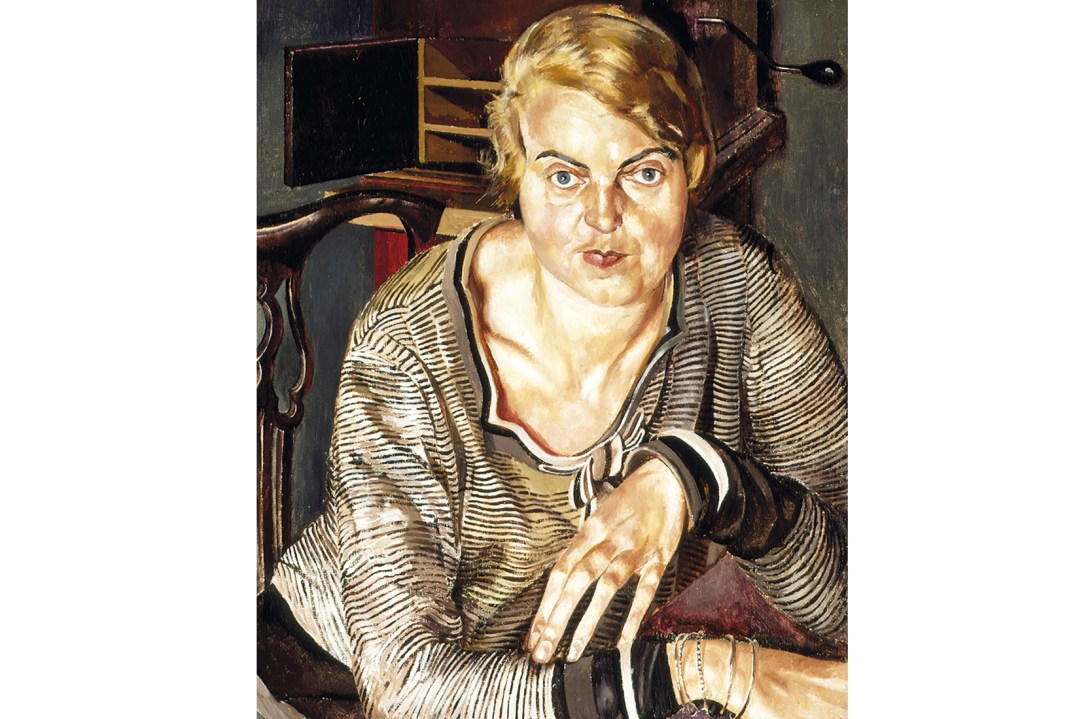

There were basic incompatibilities. He was wedded to Cookham, she to Hampstead. She was a Christian Scientist for whom the material world was an illusion, he was an evangelical realist for whom all material things were ‘a physical sign of an inward and spiritual grace’ — especially cosy, homely things that reminded him of childhood. Hilda was an artist, not a homemaker. A penetrating self-portrait of 1923 suggests a melancholic streak, which manifested itself when she found herself stranded with two young daughters in the ‘meaningless’ landscape of Burghclere while Stanley laboured for five years on his Sandham Memorial Chapel murals. Luckily, cheerful local girl Elsie Munday stepped into the domestic breach. Stanley enthused about her joy in simple things — ‘cinemas, motor-bikes, boys’ — and drew her squinting dubiously at his measuring pencil while he squats at her feet.

The female ingredient missing from Stanley’s life was glamour, and he found it, to his delight, back in Cookham, where the artists Patricia and Dorothy had moved from London. The flirtatious Patricia awakened ‘new sexual ideals’. He failed to notice that she was a lesbian, a problem she didn’t bring to his attention: he was a well off artist and she and Dorothy were skint. With Hilda increasingly away in Hampstead, the besotted Stanley showered his new love with gifts. An itemised list of jewellery among his papers records 23 purchases totalling nearly £1,000. It includes the diamond and ruby ring and diamond and amethyst necklace she flaunts in the curious composition, ‘Patricia at Cockmarsh Hill’ (1935), its awkward focus on the nape of her neck emphasising the match between the amethysts and the nearby thistles.

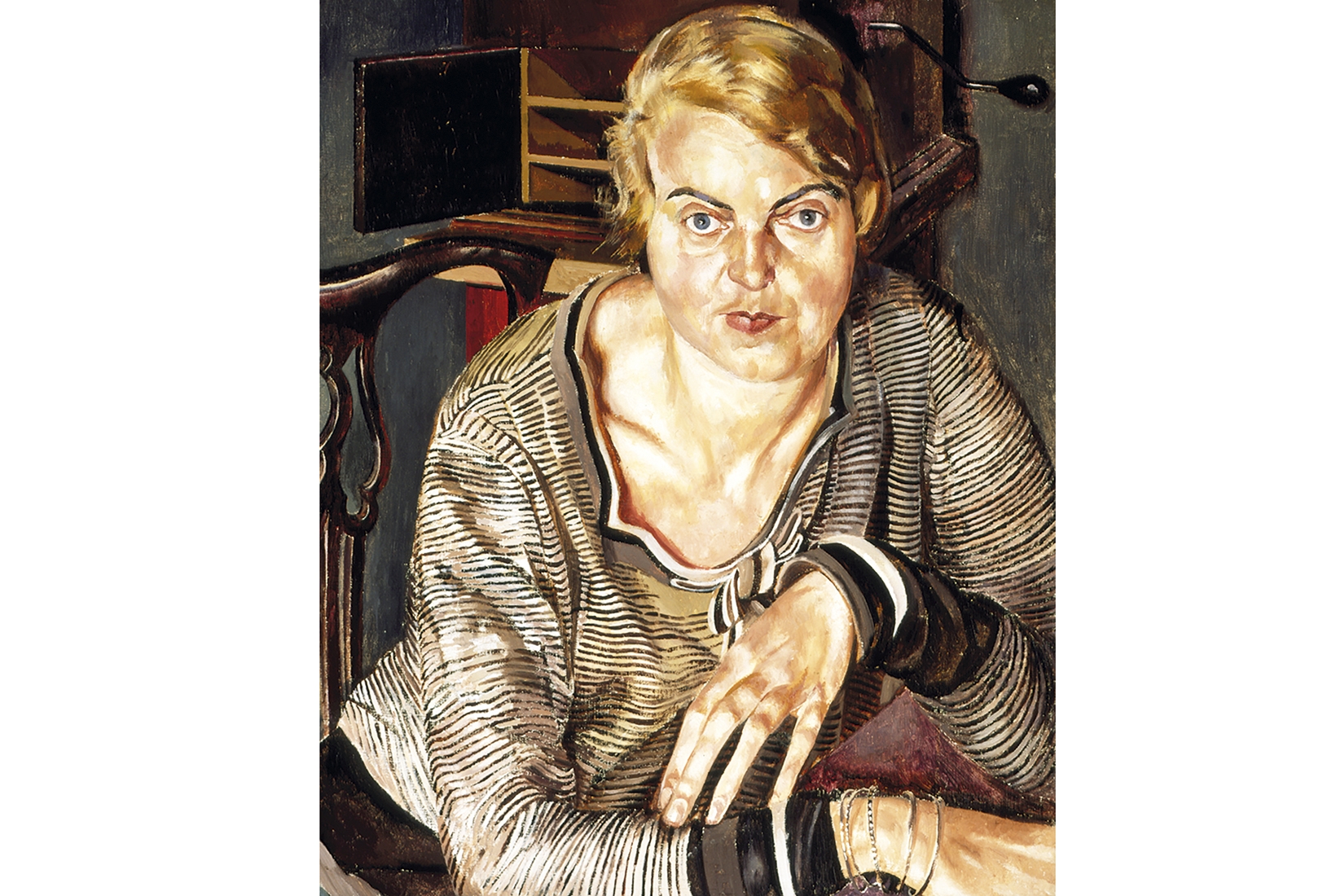

The original plan was to paint her nude in this landscape, but the ‘naked portraits’ that followed were claustrophobically confined indoors. There are no examples in this exhibition, though it does include the first clothed ‘Portrait of Patricia Preece’ (1933); the eyes are wide but far from innocent, and the twist in the ruby lips gives the game away. In the end she took him for more than jewellery. While she continued to live with Dorothy, he was obliged to earn double alimony by painting the potboiler landscapes he loathed. In 1938 she turfed him out to the garden studio and rented the house he had transferred to her name. Eventually he decamped to a bedsit in Swiss Cottage where he painted the ‘Christ in the Wilderness’ series. ‘I am full of self-pity and I need it, it will come from nowhere else,’ he sensibly reflected.

Stanley never got shot of Patricia; she refused to divorce him, hanging on to become Lady Spencer in 1959, the year of his death. But the person who most deserves our pity is Hilda. Any woman would be driven mad by a husband like Stanley, and she was. After her mental breakdown in 1942 he visited her every Sunday in Banstead Hospital, where they read from one another’s letters. Stanley had always written to Hilda during their separations, and he continued after her death. The last drawing in the show, a study for the unfinished ‘Apotheosis of Hilda’, shows her frowning crossly over one of his letters. Well, at least he had a sense of humour.

Comments