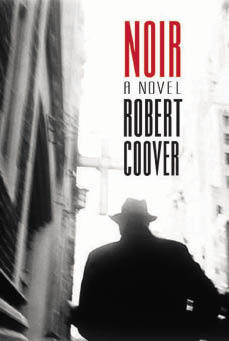

Robert Coover’s Noir is a graphic novel.

Robert Coover’s Noir is a graphic novel. Not literally, in the contemporary sense in which the phrase is used to designate a highfalutin words-plus-pictures album; but figuratively, in that its language cannot help but be converted, in the reader’s inner eye, into a series of monochromatic images, images suggestive less of a film than of, precisely, the layout of some neo-noir comic-strip. Frank Miller’s Sin City, for instance.

Like Miller, Coover pulverises the film noir aesthetic to a hallucinatory essence. In a conceit subsequent pasticheurs will find it hard to improve on, he actually has the nerve to name his private eye Philip M. Noir (‘M’ presumably standing for ‘Marlowe’). Noir’s unruffled, seen-it-all secretary (horn-rimmed spectacles, natch, but surprisingly sheer and sexy gams whenever she’s prepared to expose them) is called Blanche, which means that, as a team, Noir et Blanche, they themselves personify the quintessential colour scheme of the genre’s nocturnal atmospherics, not so much neo-realist as neon-realist. The traditionally private-eye-loathing chief of police is one Inspector Blue; the elusive master criminal, Mr Big, comes, so far as one understands, from a long line of Bigs; and the unnamed metropolis in which the action unfolds is a gangrenous hellhole of gamblers and grifters, shopworn showgirls and single-minded, double-crossing bitches as hard as the nails they never stop polishing.

In short, like Blanche, we’ve seen it all before. Which is, needless to say, the point. On occasion Coover will even tip his fedora to a specific conceit from a specific film noir — the naked, orifice-less mannequins from Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss or the shattered-mirror shootout of Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai. And though it does contrive to spring a couple of major twists on the reader, his plotline is, wholly intentionally, a clan-gathering of clichés, a convention of conventions.

What makes the novel more than an arid exercise in hip postmodernism is its style. Coover is a brilliant writer. I employed the word ‘essence’ above, and that essence is not only captured in the overall narrative slipstream but encapsulated in countless single sentences. When a woman crosses her legs, her nylons softly whisper ‘as though through lips not fully puckered’. Dockside debris is described as ‘snuggling in the rocks’ (that ‘snuggling’ is unexpectedly vivid). A severed hand is discovered in an empty hallway ‘as if it had strolled there on its fingertips’. Noir says of the anonymous city down whose dark streets he walks alone, ‘The place itself is filthy, smoky, gloomy, rank. It’s you.’ One can’t get more quintessentially noir than that.

‘It’s you.’ In fact, in its most radical divergence from conventional novelistic practice, Noir is written in the second-person singular. E.g. ‘You looked around for something to wear. All you could find was your hat’, and so on. This is by no means a first — the most celebrated example remains Michel Butor’s 1957 novel La Modification. Nor is it as annoying as might be supposed: one very quickly gets the hang of it, just as one does when watching Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake, a film noir in which Philip Marlowe is played throughout, so to speak, by the camera. But therein lies a puzzle. Lady in the Lake has always been referred to as a film in the first-person singular, Noir is written in the second-person singular. Yet the effect is identical.

Comments