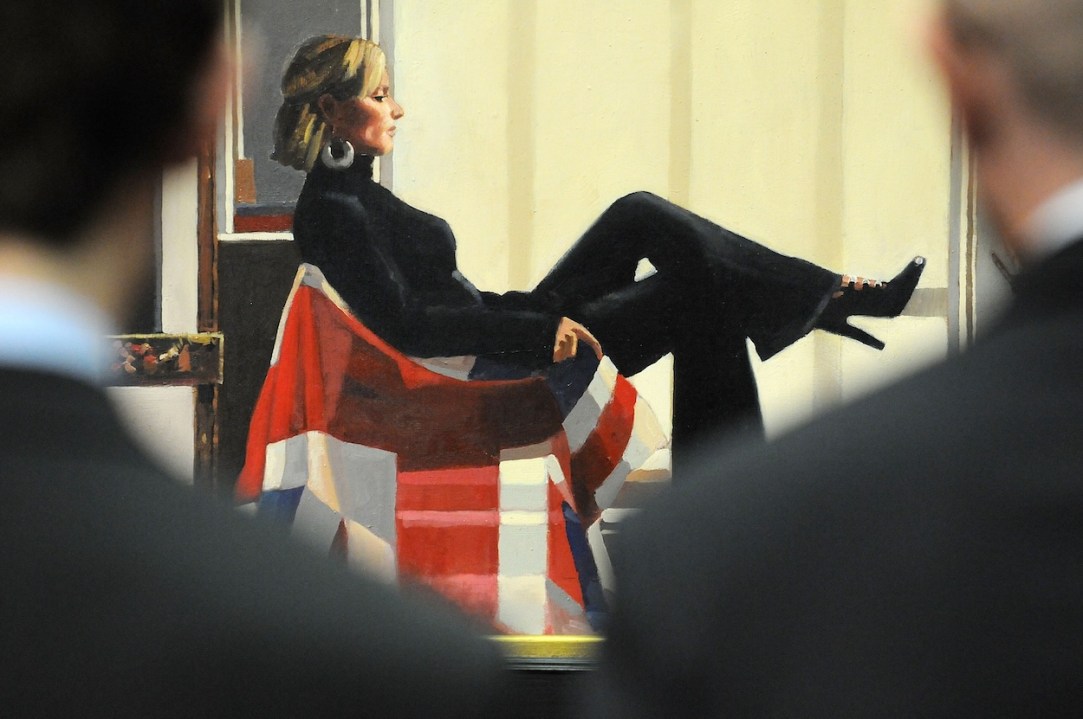

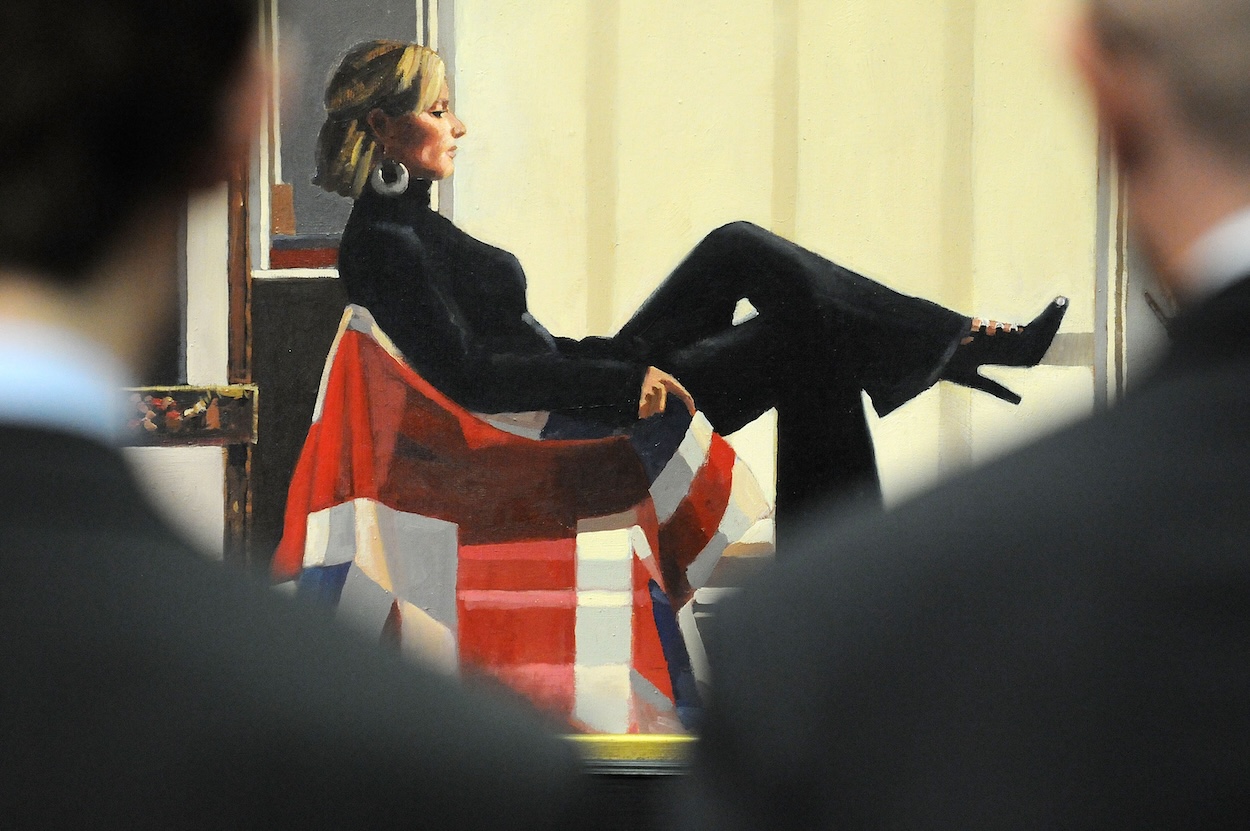

The death of the painter Jack Vettriano at the age of 73 is sure to delight at least one art critic: the Guardian’s Jonathan Jones. Jones has consistently attacked the creator of The Singing Butler, Britain’s best-selling single image, as ‘brainless’ and ‘not even an artist’. He derided his work as ‘a crass male fantasy that might have come straight out of Money by Martin Amis.’

Nor is he alone. The Daily Telegraph sneered that Vettriano was ‘the Jeffrey Archer of the art world’, and the director of the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art refused to include his work in the collection, saying, ‘I’d be more than happy to say that we think him an indifferent painter and that he is very low down our list of priorities (whether or not we can afford his work, which at the moment we obviously can’t). His “popularity” rests on cheap commercial reproductions of his paintings.’

Vettriano has long been the critics’ whipping boy, and no doubt he made his peace with that long before his demise. It helps to be selling your work for between £50,000 and £200,000 a painting, and that’s before the royalties from reproductions, the signed limited edition prints and the commemorative biscuit tins for Marks & Spencer. The latter seemed especially appropriate, as his detractors liked to sneer that his work was no more accomplished than the illustrations that manufacturers usually commissioned. Reading some of the more hysterical denunciations of Vettriano’s work, you begin to wonder what, exactly, he had done to these critics. Had he seduced their wives, stolen their cars or run off without paying a debt?

In fact, far from the stuffy embodiment of middle-class middle-brow taste that his work might suggest, Vettriano was a thoroughgoing libertine whose bad behaviour gave the lie to the apparent restraint of his artwork. At 36, he left his wife in a self-conscious effort to emulate his hero Paul Gauguin – though instead of heading to Tahiti to consort with nymphettes, he moved to the rather chillier environs of Edinburgh. Over the years, he also ran up an impressive array of addictions, which at various points included alcohol, gambling, amphetamines, ‘sexual misbehaviour’ and antidepressants. His self-conscious dedication to being a licentious and hard-living rock star of the art world made him a far more likeable and interesting character than most would believe. How can you not warm to someone who, arrested in his sixties for drink-driving and in possession of drugs, has the wherewithal to say, ‘You know who I am. We can sort this out’?

Perhaps Vettriano will posthumously receive his due as an enjoyable and accomplished painter

Even his work does not deserve the censure that it has received. It would be difficult to claim that The Singing Butler, which sold for nearly £750,000 at auction, really is a great piece of British art. Vettriano himself would agree with you. He told the Daily Telegraph in 2010: ‘I think that the success of The Singing Butler and other beach paintings puts you in a kind of awkward place where you think, “Now, if I keep on doing this I will be forever known as the guy that did the beach paintings,” and I don’t want to be remembered for that.’

But it is still possible to argue, as the artist did, that ‘If you’re sitting in Grimsby on a wet Tuesday afternoon and you’ve got that on your wall, you can drift away.’ Art as escapism? Perish the idea. Yet that was one of the central tenets of the impressionist movement – accessible, everyday paintings – and after its own lengthy period of ridicule and incomprehension, it is regarded as one of the most important movements in history.

Perhaps Vettriano will posthumously receive his due as an enjoyable and accomplished painter whose work has been enormously popular with those who want to have something that they like to look on their walls. In any case, its creator is now past caring. He once remarked: ‘I’m not in the same league as Lucian Freud or Francis Bacon. I know my place, and it isn’t up there. But I am popular and it grieves me that some people associate popularity with trash. It’s a terribly snobbish view.’ It is hard not to agree.

Comments