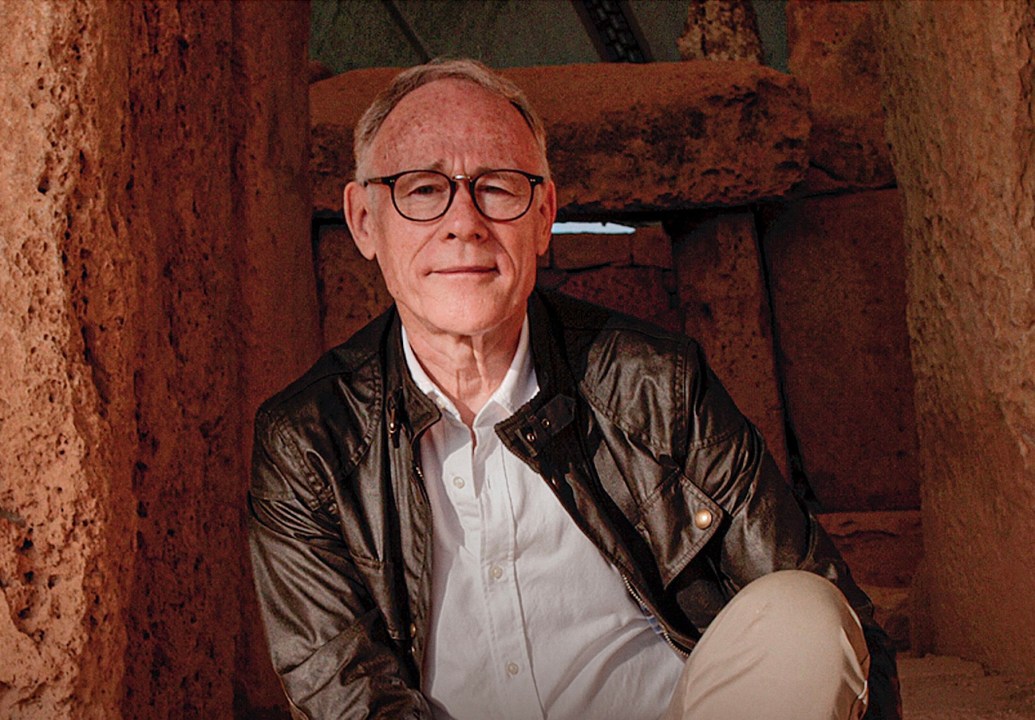

British writer Graham Hancock has riled the archaeology community with his Netflix documentary, Ancient Apocalypse. The series follows Hancock to ancient sites around the world in pursuit of proof that an advanced human civilisation existed thousands of years before the first cities of Mesopotamia. Hancock, a former Economist correspondent, argues that most archaeologists are too stubborn to admit even the possibility of such a civilisation.

Several archaeologists have rebuked Ancient Apocalypse since its release in November. They claim that it propagates false theories, avoids inconvenient facts and regurgitates old beliefs about ancient myths. One Guardian columnist called it ‘the most dangerous show on Netflix’. Flint Dibble, a research fellow at Cardiff University, described it as ‘an eight-part conspiracy theory that weaponises dramatic rhetoric against scholars’ on the Conversation.

It is true that Hancock fails to execute the documentary that might have supported his ambitious theory. He refers to himself several times as a ‘journalist’, yet includes only one source who contradicts his own viewpoint throughout the entire series. The sources he does rely on are often of doubtful expertise. Every question is loaded. But once you cut the melodramatic production and awkward camera angles away, an important point remains.

Academia, and thus scientific research, has become an irrefutable source of knowledge in British society. In debates among friends, a participant need only find the most convenient academic paper to render subsequent opposition futile. In news media, journalists refer to research as if it were gospel. The institution of science has become de facto judge, jury and executioner.

Academia is fallible at a basic level because it is performed by people. People make mistakes. They’re also subject to corruption and arrogance

Many accept this state of affairs because our society perceives science as an omniscient and objective power. This absolute adherence is dangerous because, as Hancock attempts to show within archaeology, academia makes mistakes. This happens in every scientific discipline. As Bertrand Russell wrote in his History of Western Philosophy: ‘It was supposed that atoms are indestructible… until the discovery of radio-activity, when it was found that atoms could disintegrate… The physicists invented new and smaller units, called electrons and protons… Unfortunately it seemed that protons and electrons could meet and explode, forming not new matter but a wave of energy.’

We form hypotheses based on the information available to us. But when we misunderstand that information, or when new information appears, we must reconsider the original hypotheses. Dibble calls this ‘progress’ in his polemic on the Conversation. Scientific progress, though, requires a new proposition to be proven truer than an existing one. That existing proposition then becomes wrong.

These mistakes happen in practice, too. It is within living memory that European doctors prescribed thalidomide to pregnant women, discovering years later that it could cause deformities and miscarriage. As many as 100,000 babies were killed or deformed, according to the Thalidomide Trust. The drug’s manufacturer only published an apology in 2012.

Academia is fallible at a basic level because it is performed by people. People make mistakes. They’re also subject to corruption and arrogance. Academic research is also fallible at a systemic level. People perceive it as unbiased because those who perform the research receive their salaries from non-profit institutions. Yet universities must still compete to attract the best students. That competition has been based on the quality of their published research in the past. This research is published in academic journals that, as commercial companies, are subject to the biases of any profit-making organisation. The parent company of one of the biggest of these academic publishers, Elsevier, reported a profit of more than £2 billion in 2021.

A friend who works in research at one of our country’s best universities gave me an example of this a few years ago. He had been collecting data on a sample of hundreds of participants. Once he had analysed the data, the results showed almost no difference between the study’s control and variables. The project’s director, a professor, told him to adjust the metrics of his analysis until the results presented a difference.

I do not mean to suggest that we should rely on our instinctual knowledge, refuse vaccines and believe in every alternative theory we encounter. Academic research has been one of the most valuable developments of modern society.

I propose, though, that we recognise scepticism as a beneficial element of human society. We make ourselves vulnerable when we fail to ask questions about entrenched views. Diversity of opinion should be as welcome to a 21st-century Britain as diversity of experience and race.

‘It’s my job to offer an alternative point of view,’ Hancock says in Ancient Apocalypse. ‘The common argument is: we are archaeologists, and we know best. I think it’s worth discussing.’

Comments