More than 40 years on, every town still has them, wandering the streets with pale skin, more make-up than you can find in Superdrug, swathed in acres of black fabric. Goths, rather unexpectedly, have turned out to be the great survivors among pop subcultures. Others have risen and faded, but the goths – laughed at, ignored, dismissed – have endured, seeing their style and their musical tastes slowly incorporated by everyone else (there’s even a goth version of hip-hop, known as ‘horrorcore’).

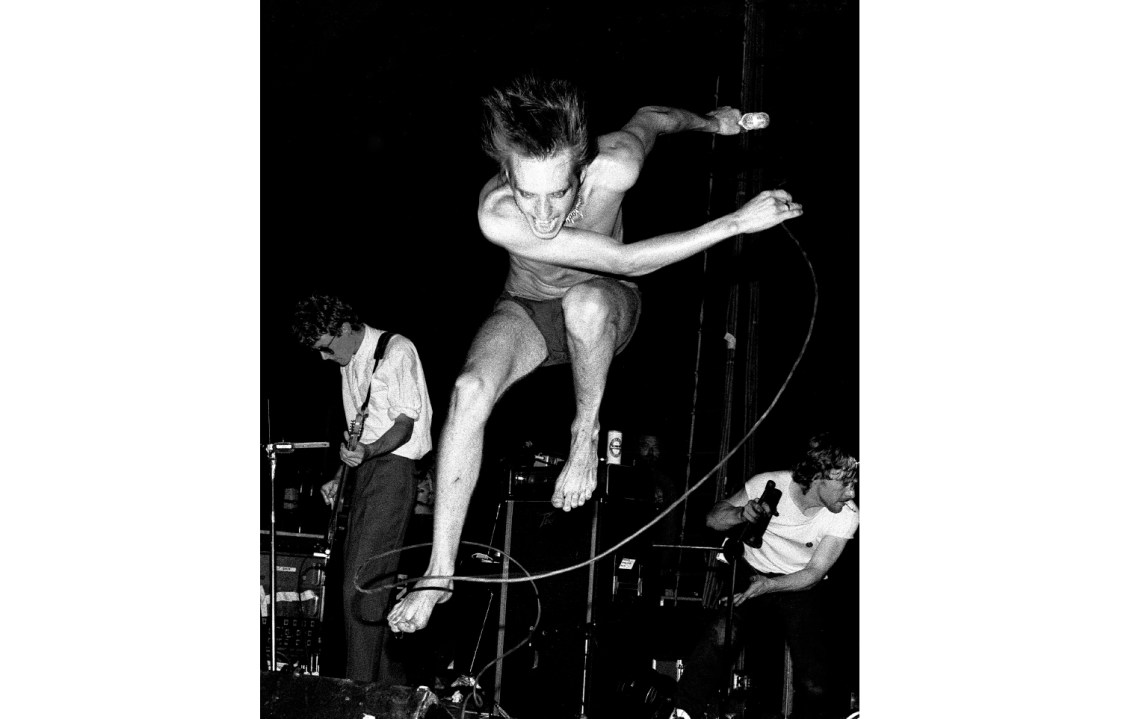

Goth was a fitting name for the music: overbearing and foreboding; delivering ecstasy through the building and releasing of tension rather than through major chords and primary colours; drawing on punk, Bowie, the Doors and the Stooges. But it wouldn’t have been called goth without the aesthetic, a see-what-sticks mélange of the sexy and dangerous – a bit of Byron, De Sade and Crowley, a dollop of the kitsch 1950s LA celebrity Vampira, and anything else that came to hand.

Others have risen and faded, but the goths – laughed at, ignored, dismissed – have endured

The idea that this music was gothic was there from the beginning – in 1980, NME described the first album by goth heroes Bauhaus as ‘Gothick-Romantic pseudo decadence’ – but it only became a catch-all for every band with back-combed black hair during 1983 and 1984 (the NME had tried naming the nascent scene ‘positive punk’ but it didn’t catch on). Since then, though, only historians have thought of goths as anything other than people with a love of kohl and snakebite and black.

But this year they’ve been dragged from the dark corners into the spotlight. There’s a new box set, Young Limbs Rise Again: The Story of the Batcave 1982–1985, compiled of music played at the Soho club night that was instrumental in spreading the word of the subculture. The music writers Cathi Unsworth and John Robb have both written epic histories of the goths (hers is Season of the Witch, his Art of Darkness) that recount the histories of the bands and dig into their inspirations (often non-musical – the original goths loved their romantic poets and the doomed pre-Raphaelite maidens). There are other books coming, too, by musicians – one from Lol Tolhurst of the Cure, one from Wayne Hussey of Sisters of Mercy and the Mission.

The Batcave was set up by the members of the band Specimen to give them somewhere to play, and quickly became a magnet not just for thrillseekers, but for scene-makers – the likes of Nick Cave and Siouxsie and the Banshees were among the visitors. ‘The people who were coming were doing stuff: in fashion, in music,’ says Jon Klein, who played guitar with Specimen and, later, the Banshees. ‘Marc Almond was a regular, so was Lemmy. Boy George used to come down a lot. There were no paps, so it wasn’t a place where people would get hassled.’

Central to it all was that goths, more than most subcultures, were about reinvention. Anyone who has ever had a goth friend knows the transformation that happened once the clothes and make-up went on. ‘It levelled the playing field between really pretty people and normal people. If you could make yourself up and dress up, you could change the way you were perceived. People lost their inhibitions. They felt more confident and happier in their skin,’ says Klein. ‘I used to harp on about how you could change the world if you could change your own world, but I do wonder who expected it to last this long.’

‘The look was a suit of armour, and it scared off the beerboys,’ Cathi Unsworth says. ‘Once I adopted that look, boys who had been horrible just shut up. Women like Siouxsie were role models. They were brilliant and uncompromising and wanted women to be empowered. They wanted to help women along with them.’

But while the Batcave was the high-fashion end of goth, its truest expression was in the regions and the provinces, especially in West Yorkshire – particularly Leeds – where bands such as Sisters of Mercy, Southern Death Cult (later Death Cult and, later still, arena stars as the Cult), March Violets, Skeletal Family and Red Lorry Yellow Lorry were embracing and promoting the darkness.

It was provincial, John Robb suggests, because it was a grassroots subculture – driven by the participants rather than by the media. ‘The music press at the time was channelling post-punk,’ he says, ‘but people had their own ideas about what they wanted to do. All these small towns had their underground clubs. There were convergent evolutions – people knew about the Batcave, but the Phono in Leeds came first. I like the way it was self-created, even though the London media liked to have control of things. There’s something amazing about creating culture in isolation – about a band like Bauhaus arriving fully formed from Northampton, where there might have been ten people creating amazing culture.’

Goth culture became especially closely linked with Leeds. When I went to university there, in 1987, there were students who had chosen to study there specifically because it was Goth City. That, Unsworth says, was thanks to a nexus of people and events: not just the Phono (commemorated in the Sisters of Mercy song ‘Floorshow’), but also its DJ, Claire Shearsby, who helped inspire the Sisters’ singer and leader, Andrew Eldritch, and the F Club, the local punk night of no fixed abode that brought together the people who would form the core council of Goth City.

The Yorkshire bands were perhaps the key to why goth became such a dirty word in the British music press. At a time when music writing was becoming staunchly opposed to ‘rockism’ – denouncing the crimes of the pre-punk generations – the Yorkshire bands were unashamedly rock, even if they pulled it in new directions (Sisters of Mercy were the first major rock band to employ a drum machine, Doktor Avalanche, instead of a human drummer).

‘It annoys me that it was seen as stupid and morbid. It was creative, inventive, hilarious’

‘What was interesting with Sisters was the idea that it was both ironic and brazen at the same time,’ Robb says. ‘There was that Yorkshire stubbornness – “No, we like rock!” Whereas in Manchester and Liverpool, for young bands it was all about “not being rock”.’ At the other end of the M62, for example, Echo and the Bunnymen – a band who drew on many of the same influences as the goth bands – were explicitly proclaiming themselves ‘anti-rock’ by putting Pete De Freitas’s drum kit at one side of the stage rather than back centre, like everyone else (it seems extraordinary, now, to think how much such tiny distinctions mattered).

By the late 1980s, goth had become its own caricature, helped along by the sneering music press. But it never disappeared. The clubs continued to exist, the clothes continued to sell, and the music begin to intertwine with other styles to fill stadiums and arenas – Depeche Mode more or less reinvented themselves as a goth band with synthesisers, for example. And the goths – like that other much-mocked tribe, the metalheads – kept to themselves as their world got bigger and bigger.

It will always hold appeal, Robb says. ‘It’s the darkness. People have always told ghost stories and embraced the melancholy. It was not a morose scene; there were lots of parties and good times.’ It’s a point echoed by Unsworth: ‘It annoys me that it was seen as stupid and morbid. It was creative and inventive and hilarious. Otherwise why would people still be attracted to it?’

Jon Klein still sees the effects of what he was doing 40 years ago as a young man. He recalls painting the logo for the Batcave’s membership cards in Tippex, taking just seconds to doodle something. ‘For our 25th anniversary, we did a festival in Lithuania and a guy turned up with that logo tattooed on his neck, carefully replicating the fading Tippex.’ He laughs with wonder at how the world turns.

Young Limbs Rise Again: The Story of the Batcave is out now on Demon. Art of Darkness: The History of Goth by John Robb is published by Manchester University Press. Season of the Witch: The Book of Goth by Cathi Unsworth is published by Nine Eight Books.

Comments