There are so many ways to express love in French that it’s easy to make faux pas. My faux pas over the five decades I’ve been speaking French are legend – at least in the family. Best to keep them there.

Most people know that ‘Je vous aime’ means ‘I love you’ and covers one or more people. If you say ‘Je t’aime’, the informal expression of love for one person, you’ve got to be careful. Especially in today’s world where ‘hooking up’ is more common than rabbits breeding.

We speak a lot of Franglais in our family – we’re creative and lazy when it comes to language. With bilingual grandchildren it’s inevitable. A few years back, one grandson came up with ‘On y go’ for ‘Allons-y’. We all prefer his version. When the same grandson (age nine) recently showed more than a passing fancy in a pretty school mate (normally une petite amie), his six-year-old sister spilled the beans to me about his amoureuse. The noun can be a pal, as well as lover, or the object of a crush – more likely the latter at his age. When I tickle one of them, I say ‘Je t’aime’. When I’m tickling both of them at the same time, I say ‘Je vous aime’.

‘Just write that you questioned an old, happily married couple who wondered why French, the supposed langue de l’amour, doesn’t have a word for “hook-up”,’ I told the student

A few years ago, my husband, Richard, and I were chatting and tickling our grandchildren, declaring our love for them, in front of the lovely fountain in the village square of Meursault, in Burgundy, where our family lives. A young man, who had been watching our grandparental antics, approached. He was doing an essay for his Bac (short for the Bacalauriat, the exam necessary to get into university) and wanted to know if we could answer some questions about love. Richard rolled his British baby blues.

The student had overheard us speaking Franglais and he thought we’d have an interesting perspective on the subject of love; not just any love, but elderly, English love. When he tried to explain in broken English what he wanted to know, I started to answer him in French. Then I switched to Franglais.

‘How many years have you been married?’ he asked.

‘Quarante-six.’

‘When did you – ahem – realise that you were in love – ahem – begin a relationship?’

‘Relationship?’ I was confused. Did he mean when did we fall in love?

‘Yes, ahem…’ he answered timidly, not wanting to really ask what he wanted to know.

‘We were engaged for six months.’

‘I mean – ahem – share your love.’

‘Oh!’ I exclaimed. ‘He wants to know when we started sleeping together,’ I whispered to Richard. ‘You mean hook-up?’ I asked the student.

‘Oui, hooook-up,’ he answered, blushing from tête aux pieds. He thought he’d made a faux pas. It was clear that French didn’t have a word for hook-up – yet.

I let him off the hook gently. I am usually kind to polite, well-dressed, well-meaning teens – especially since there are so few nowadays. ‘Just write that you questioned an old, happily married English-speaking couple who wondered why French, the supposed langue de l’amour, doesn’t have a word for “hook-up”,’ I said. He smiled and thanked me. I wished him bonne chance with his essay and hoped that he used our encounter to write something creative about elderly English amour.

When Richard and I got home, we googled to find out how the French get by in this day and age of instant gratification without a word for ‘hook-up’. One way, the internet told us, is by admitting to having had an aventure. For Richard and me love had been a great adventure – all 46 years. Even that afternoon by the fountain with our grandchildren we agreed that nous nous aimons beaucoup. The French, with their complicated verbs, at least realise that to be loved by those you love is best.

A five-point guide to langue de l’amour

1. The French can be very direct. However, when it comes to speaking about love, French nuances are legion and start with aimer: it can mean to like as well as to love. French doesn’t have those three little words, ‘I love you’. But it does have je t’aime. Adorer is a step up from aimer. A cheesy example: j’aime le fromage vs j’adore le fromage – especially aged cheese. Often heard: ma puce (flea), mon chou (cabbage) – perhaps inspiration for Prince Philip, who called the late Queen ‘Cabbage’.

2. It’s good to remember that, even though you see the French doing a lot of air kissing (usually two – although the closer you get to the Mediterranean, two becomes three or four), lips don’t touch cheeks and quantity is more significant than quality.

3. According to Berlitz: ‘French people usually don’t have the “we are exclusive” conversation – there is little nuance between dating and exclusivity’. Nevertheless, even though there is no French word yet for hooking up, sortir avec, to go out with, is often used if dinner and/or a movie are a date. But the French do have one-night stands. In contemporary French slang, making out is rouler une pell – literally, roll a shovel. It refers to the shape of the tongue during deep kissing. If you want to have safe sex, a FL (French letter) might enter into a dialogue. It refers to the small, carefully wrapped paquets that the Brits issued their soldiers, who then shared with their more sexually liberated but less prepared French buddies. Younger generations use condom or the slang une capote.

4. According to the comedian Guy Blaise in Love Like the French, after a very satisfying night of love, your partner might say he had a petit mort – died and went to heaven. Let’s not forget the French are poets when it comes to love. If he says ‘Bon jour, mon amour’ after a night of passion, that might be a first step towards becoming his moitié (better half).

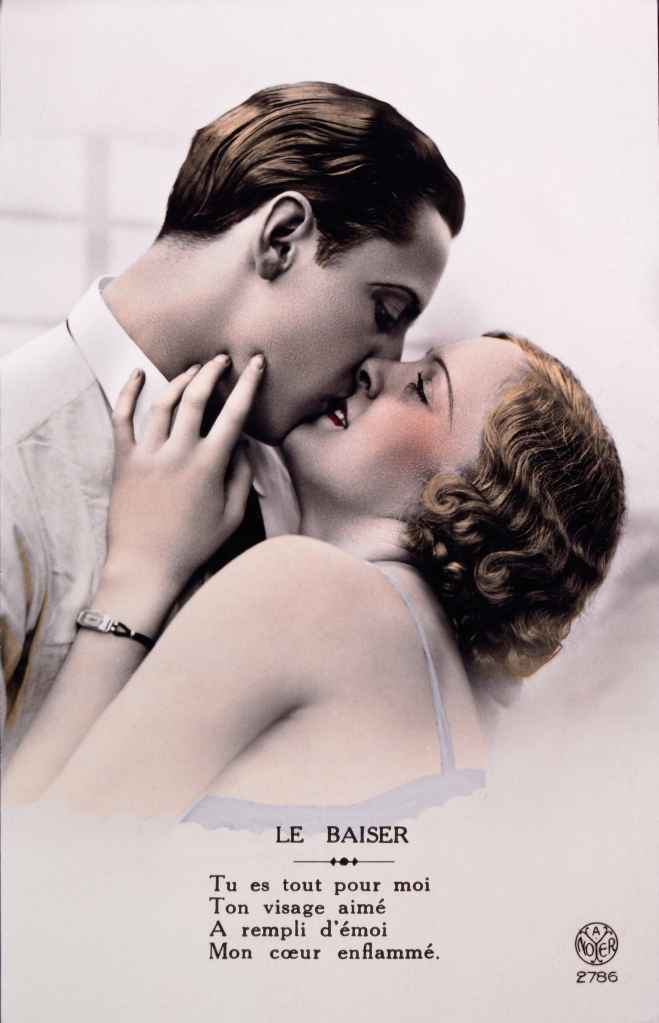

5. The verb to flirt is flirter. But the French didn’t invent flirting. Flirter comes from conter fleurette, or to whisper sweet nothings in one’s ear. Warning: the noun for a kiss is un baiser and the verb, baiser, is a crude word for sex. To mix them up could lead to un faux pas gigantesque.

Comments