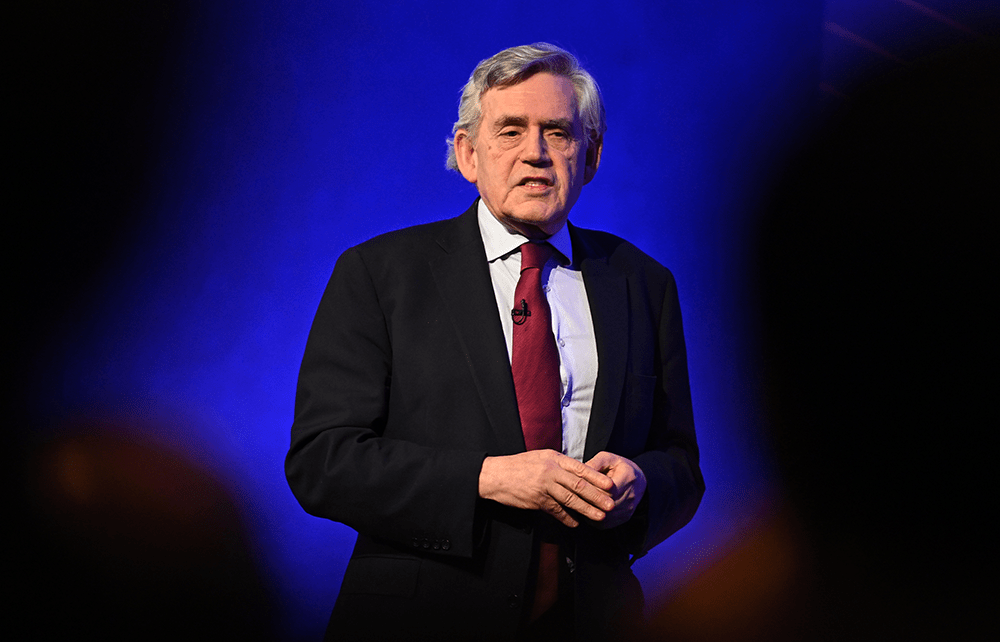

Last week, there was a surprise visitor to the Treasury: Gordon Brown. The former prime minister and chancellor secretly returned to his old digs for the first time since he left office 14 years ago. According to onlookers, Brown visited his old office as he caught up with the new chancellor – and his friend – Rachel Reeves.

To Brownites, news of this meeting has been received with glee. Is their main man back in the fold? The conversation between Brown and Reeves is part of a pattern for this government: New Labour old-timers returning to share their wisdom with first-time ministers. In the Department of Health, Wes Streeting has Alan Milburn and Paul Corrigan while Dan Corry, Brown’s former head of the No. 10 policy unity, is leading a review of environmental regulation.

‘I voted for the winter fuel cut. But we need a sense of what the point of all this is’

Although Reeves was perhaps closer to the late Alistair Darling, she has long admired Brown for his grasp of economics. She once instructed her staff to watch YouTube videos of the shadow Treasury team in 1996, who were already using phrases such as ‘neo-endogenous growth theory’. ‘She doesn’t want to rely on others to do the maths,’ explains an insider.

These days, however, Reeves is most frequently compared with another chancellor: George Osborne. Even though Reeves found the funds for big public sector pay rises, the left of her party worry that the ghost of the austerity chancellor is haunting the Treasury. It was Brown who introduced the winter fuel payment after the 1997 election saying he was ‘not prepared to allow another winter to go by when pensioners are fearful of turning up their heating’. The Tories didn’t dare scrap it. Reeves has.

All opposition parties – Reform, the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives – united against her cut. The Labour left and the unions have also been seeing red, accusing Reeves of reviving Osbornian austerity. Keir Starmer’s majority is so large that even his largest rebellion to date (52 MPs were absent for the vote) meant the motion still passed comfortably. Reeves had faced calls to soften the policy. However, for both No. 10 and No. 11, who wanted to send a message that they do not cave under pressure, the vote had become a symbolic test.

Reeves has warned Labour MPs that there will be more difficult decisions. ‘I don’t say that because I relish it,’ she told them in a private meeting on Monday. ‘It’s a reflection of the inheritance that we face. When members are looking at where to apportion blame, I tell you where the blame lies. It lies with the Conservatives and the reckless decisions they made.’

By attempting to direct the anger over her tax rises and spending cuts towards the Tories, she is using a tactic from the Cameron/Osborne playbook. Reeves’s allies believe that the coalition government were so effective at blaming austerity on the previous lot they managed to keep Labour out of power for successive elections.

When Starmer was elected as party leader in 2020, he asked Anneliese Dodds to be his shadow chancellor. Only later, when the threat from the left had been neutralised, did he replace her with the more fiscally conservative Reeves. She and her team view fiscal responsibility as their priority, rejecting the fashionable notions of borrow-and-spend ‘modern monetary theory’. This approach recalls Brown’s first term as chancellor when he pledged to stay within the inherited Tory spending plans.

An upcoming review of the general election by the thinktank Labour Together – which is viewed in No. 10 as the definitive account – is expected to find that voters’ trust in economic competence was a driving factor in Labour’s victory. Labour was viewed as more competent than other parties by Conservative to Labour switchers, the voter group viewed as key to Starmer’s election win. The party could finally brush away memories of James Callaghan’s Winter of Discontent.

Morgan McSweeney, Starmer’s most influential adviser, places similar importance on economic competence – hence his support for Starmer’s gloomy statement that ‘things will get worse before they get better’. The messaging is being driven by No. 10’s political unit. The hope is that they can switch to a happier, higher-spending Budget later, as Brown did in his second term. Both Starmer and Reeves say they can handle unpopularity in the short term.

The bigger question in Labour circles is whether Reeves will end up acting more like Osborne or Brown. Even in the Tory party the jury is out as to whether those cuts were the right decision, given the unexpected collapse in borrowing rates. The Brown splurge, by contrast, brought the biggest expansion of the state ever seen in peacetime. Another one of Brown’s theories is that state spending is a ratchet, easy to move up but hard for Tories to move down. Big-state countries, he argued, tend to vote left.

Reeves may well be planning her own version of ‘prudence for a purpose’ but that purpose is unclear to many of her colleagues. Given that there was no growth in the UK economy in July, there is less of a sense now that there is a natural trajectory of growth to fall back on.

Some Labour MPs fear Starmer’s gloomy messaging may hamper efforts to get companies to invest in the UK. The Institute of Directors says its surveys show a fall in optimism, which matters given that Reeves’s explicit strategy is to attract private investment by rekindling economic confidence. Next month’s Budget – which may bring in a capital-gains tax hike, pensions raid and inheritance tax changes – could further stoke fears of an exodus of top taxpayers.

The risk for Reeves is that, no matter what her intentions, she appears more Osborne than Brown – all tunnel and no light. ‘I voted for the winter fuel cut,’ says one new Labour MP. ‘I didn’t want to have the whip removed. But we need a sense of what the point of all this is.’

Comments