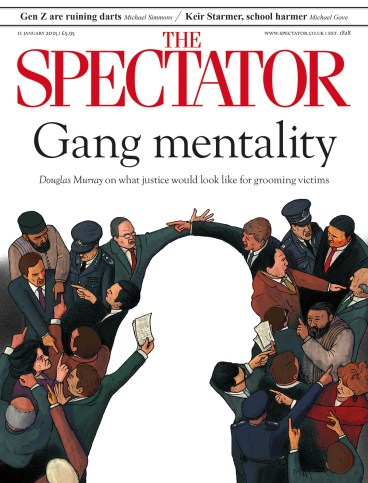

The debate surrounding the sexual exploitation of thousands of children over decades, which has re-ignited this week, should act as a reproach to the nation. The details laid out in court transcripts, in the testimonies of victims, show how completely the institutions of the state failed them.

The case for a comprehensive national inquiry to determine what further lessons still need to be learned has been well made by the leader of the opposition. The work of Alexis Jay in uncovering the terrible crimes committed in Rotherham and her subsequent wider-ranging inquiry into other areas of child sexual abuse were powerful interventions. But it is no criticism of her or her team to acknowledge that there is more that needs to be done, many profoundly difficult questions that still require detailed answers.

What is needed is to significantly increase the number of children in care who are adopted

The journalist who first brought the scale of this scandal to light, Andrew Norfolk, the former chief investigative reporter of the Times, has rightly argued that there are complex ethnic, cultural and religious factors that require careful examination. The fact that so many of the perpetrators of terrible sexual violence came from Pakistani diaspora communities raises unignorable challenges. As Norfolk has pointed out, questions of Islamic jurisprudence, cousin and arranged marriages, wider attitudes towards women and girls, and a reluctance to invite scrutiny of intra-community disputes, all need to be analysed and investigated. That such work must be handled with sensitivity is obvious. But it cannot be ducked, if we are to ensure that the attitudes and actions which have caused such terrible suffering are to be properly addressed and effectively dealt with.

Just as important, however, as addressing the factors behind the criminal actions of the perpetrators is ensuring much better protection for those who are at risk of becoming victims. It is a terrible indictment of the state that so many of those who were exploited by organised gangs were children in its care. The rape gangs that operated across England made a point of targeting vulnerable children who were in foster or residential care. These were children who had already grown up at risk of abuse or neglect, who had been taken from their birth families in order to protect them, and who were then exposed to the most horrendous crimes.

These children would often have been witnesses to, or victims of, domestic violence in their early years, and more vulnerable to further brutality as a result. Their infancies would have been characterised by an absence of affection, trust and boundaries, so they would have been more susceptible to the calculated affectation of care with which their groomers approached them. Starved of love in their home lives, they fell prey to men who appeared to offer them tenderness and then entrapped them with drugs and alcohol into sexual slavery.

Over the past two decades there have been improvements in how we support children in the care system. In the wake of rape convictions in Rochdale, work by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner led to more rigorous scrutiny of children’s homes and efforts to ensure that fewer young people were placed in settings far from their families and, as had happened too often, in placements alongside drug hostels and homes for recently released offenders.

David Cameron led efforts to ensure that more children at risk of abuse or neglect were adopted and placed in permanent loving homes rather than institutions. Sir Martin Narey, the former chief executive of Barnardo’s, produced a ground-breaking report on the education and training of social workers, which set out steps to ensure that those charged with protecting children’s welfare were equipped to rescue them from risk of harm and provide them with all the support they needed to flourish.

But the momentum for reform in children’s care slackened after David Cameron departed from office. The urgent attention he brought to increasing rates of adoption, reforming social work and challenging poor provision in children’s homes was not maintained. It is an agenda which this government should seek to turbo-charge.

What is needed is to set a target of significantly increasing the number of children in care who are adopted. This could be done by recruiting many more adoptive families, fast-tracking the process so that children do not languish in institutional or foster care for months, overhauling how the family courts work to facilitate adoption, and providing enhanced financial support for adopters. The government could also build on the work of former children’s minister David Johnston in expanding the number of kinship carers – extended family members such as grandparents – who can provide secure and loving environments for those whose birth parents cannot cope with their responsibilities.

And action should also be taken to tackle the terrible conditions which prevail in all too many children’s homes – often under the control of private equity firms who are making considerable profits from the taxpayer while the children nominally in their care live in squalid surroundings without adequate supervision. David Johnston began the process of holding these companies to account under the last government. This administration should pick up where he left off. Amid all the inevitable questions about what went wrong in the past, there are undoubtedly policies that are ready for implementation which previous Tory politicians championed and which could better protect the most vulnerable. They should be pursued without delay.

Comments