‘So suburban!’ That’s Prince Orlofsky’s catchphrase in the Grange Festival’s new production of Die Fledermaus, and he gets a lot of wear out of it. You couldn’t really describe the Grange Festival as suburban – it’s hard to imagine a corner of the Home Counties that’s more remote from urban civilisation. No, if the vibe at Garsington is plutocratic, and West Horsley is pure Stockbroker Belt, the Grange Festival is definitely county, in a comfy, faded, Aga-and-chintz sort of way. The picnic takes precedence over the opera, and you’ll see evening wear that was new around the time that Alan Coren retired from Punch.

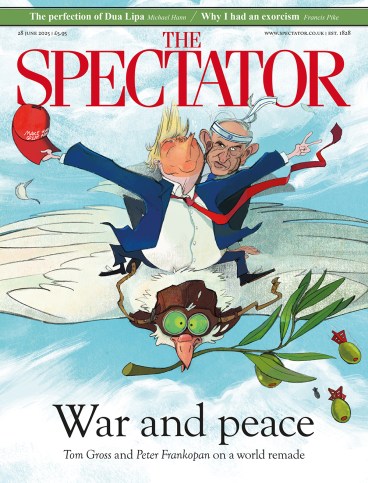

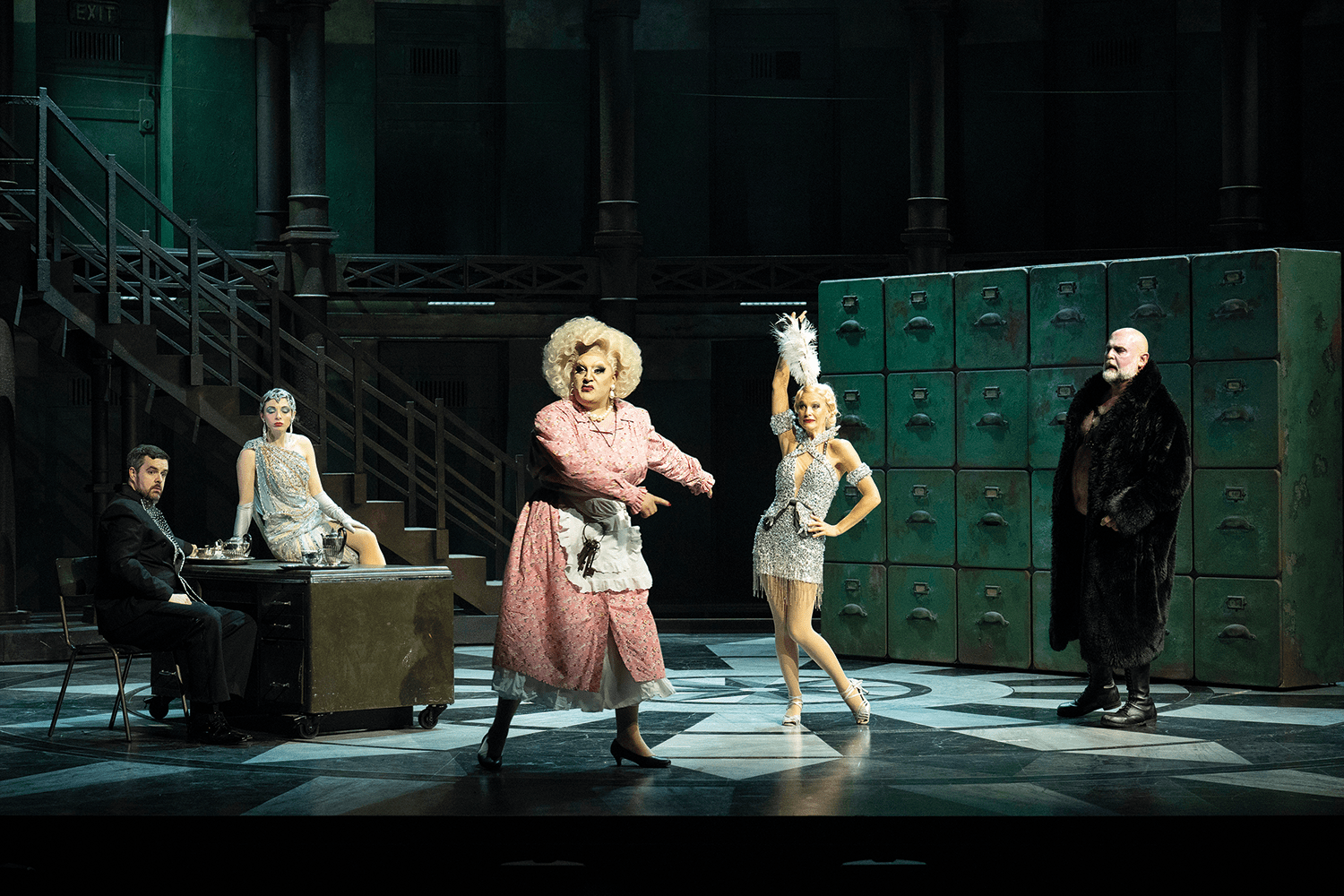

Anyway, this lively Die Fledermaus knows its public and wants them to enjoy themselves. It’s directed by Paul Curran, whose 2023 production of The Queen of Spades was the best thing I’ve ever seen at the Grange, and it’s set in a generic mid-20th century. The promotional blurb talks about the 1920s but you could have fooled me, unless you count Ida’s Josephine Baker-ish outfit in the Act Two party. Even there, though, the style is more Rocky Horror Show: men in suspenders, flashing lights and lots of cosy, old-school British naughtiness. I’ve rarely seen a happier audience; they were positively bubbling on the way out.

Paul Daniel conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, and he doesn’t hang around. No mannered imitation of Viennese style here, just warm colours, buoyant dance rhythms and a constant, energising swing. The singers didn’t always feel entirely on the same page, but that might have been first-night awkwardness. Any Fledermaus that casts Ellie Laugharne (a mockney Adele, with diamond-tipped high notes), Ben McAteer (enjoyably dark-edged in every sense as Falke) and Darren Jeffery as a larger-than-life Frank, is never going to sound too shabby – even if the supporting characters did rather overshadow the more reserved central pairing of Sylvia Schwartz (Rosalinde) and Andrew Hamilton (a very straitlaced Eisenstein).

Still, it’d be churlish to grumble when you’ve got an Orlofsky as ripe as Claudia Huckle, or (as Alfred) a tenor as sunny as Trystan Llyr Griffiths. The jailer Frosch, whose Act Three monologue can scupper or save a Fledermaus, has become Frau Frosch – a pantomime dame played by Myra DuBois, who got one of the biggest laughs of the evening by turning a spotlight on the post-supper Grange audience (‘The devil wears Bonmarché’). You need a genuinely gifted comedian in this role, and the Grange clearly has one. Odd, then, that certain gags got run into the ground, and even DuBois seemed momentarily baffled by a passing reference to El Salvador – not the first occasion that the English text emitted a musty aroma of 1980s sitcom.

Sure enough, it turns out that they’re using a translation by John Mortimer. Gloriously on-brand for the Grange, of course, but it’s a pity that they couldn’t have given the gig to one of the many excellent living opera translators who might have valued the work. And who might, perhaps, have avoided the grisly pile-up of failed rhymes, mis-stressed syllables and rhythmic distortions that dear old Rumpole apparently thought would pass muster as singable lyrics. I’m being pedantic, no doubt. Operetta is fluff and the words are disposable, right? This is the UK’s only major production of one of Johann Strauss’s stage works in this, his bicentenary year. Strauss aimed to entertain, and for this crowd, in this place, this Fledermaus does precisely that.

At Garsington, Ruth Knight’s staging of Handel’s Rodelinda divides the stage into two levels, and even labels some of the characters to help you get a grip on the plot. It works surprisingly well, though there are some bizarre choices of imagery. A royal wedding scene occurs in a minimalist restaurant: quivering slabs of pig lie on shiny counters, while a pervy-looking chef sharpens his cleaver. As is often the way at Garsington, things look a lot better after the interval, when darkness has set in and lighting effects become a serious possibility. The final scenes made wonderful play with deep shadow and flickering candles.

There’s no chorus in this opera, but Knight deploys a squad of sword-wielding, black-robed ninja dancers, who swirl menacingly around the main characters. From an impressive cast, Lucy Crowe stands out in the title role, her firm, glowing voice drooping with melancholy and making a sympathetic counterpart for Tim Mead’s equally expressive Bertarido. As the usurper Grimoaldo, Ed Lyon grappled nobly with of one of Handel’s typically ungrateful tenor roles, before – at the very last – opening out in pure, poignant humanity (this is a relatively rare Handel opera where the villain’s final redemption is more than mere narrative convention). Peter Whelan conducted the English Concert, and with their crunchy collective attack and smoky, sighing flutes, they were as colourful and as committed as anything on stage.

Join Richard Bratby at the Spectator for another in our series of Spectator Writers’ Dinners, Thursday 17 July, 7-10pm. Go to spectator.co.uk/tastings to book.

Comments