All My Sons, set in an American suburb in the summer of 1947, examines the downfall of Joe Keller, a wealthy and patriotic arms manufacturer. During the war he was falsely accused of selling wonky parts to the US military which caused the deaths of 21 airmen. He blamed his partner for the blunder but when the truth emerges he also finds out why his eldest son, Larry, went missing in action.

The plot is one of the greatest inventions in world drama and it deserves to be presented with candour, simplicity and naturalism. Director Ivo van Hove dislikes Miller’s decision to set the play on Joe’s front lawn where the neighbours mingle, chat and exchange secrets. In his version, the vacated stage is overlooked by a huge blank wall decorated to resemble a doormat.

Across the playing area lies a massive tree that crashed to the ground during an overnight storm. The shattered trunk symbolises mankind’s broken virtue but here it serves as a piece of furniture too. The players sit on the trunk or leave props lying around on the bark. So it’s not just a mythical emblem, it’s a sofa and a coffee table as well. Not ideal. Any actor who bumps into the tree accidentally makes the slender branches quiver nervously. And all the costumes are maddeningly vague. Instead of choosing the correct period, van Hove dresses his cast in cheap non-descript clothing that might belong to any decade from the past 70 years.

Music is added too. Throbbing bass lines, swelling orchestral chords, lots of random plinks and plonks. When the story intensifies, the volume rises to match it. But the viewers don’t need help from a soundtrack to follow the action.

Some parts of the story that are straightforward look mysterious. When a sharky young lawyer, George, arrives to uncover the truth he wears a tatty old tracksuit and three days of stubble. Why make him look like a homeless pickpocket? Perhaps it’s a comment on the legal profession. Or perhaps not. Van Hove’s cranky decisions can’t mar the power of the play’s thrilling finale.

Van Hove was desperate to destroy Miller but he got beaten on points

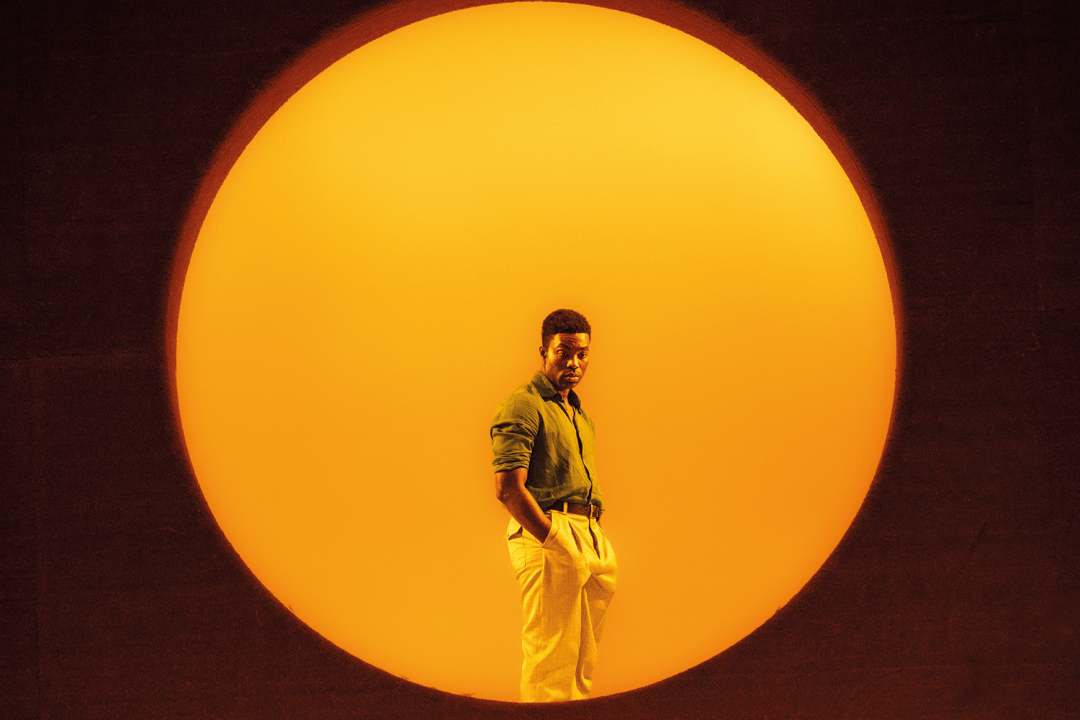

Bryan Cranston plays Joe as an amiable scatterbrain rather than as a grasping hypocrite, which is unusual. It’s a placid, easygoing interpretation that lacks grandeur. He’s more like an unfrocked jester than a fallen king. Paapa Essiedu brings his estimable talent to the tricky role of Chris, Joe’s surviving son. Essiedu is a great actor. Inventive and original, never easy to predict. But Chris is a tough call because his Buddha-like moral stature alienates everyone. Not just his neighbours. Audiences are apt to find him too good to be true as well.

The show feels like an almighty struggle between two intellectual boxing champs. Van Hove was desperate to destroy Miller but he got beaten on points.

Precipice is a musical about the end of the world. The action takes place in a tower block on the banks of the Thames where a young couple, Ash and Emily, are living together. They plan to have kids so they turn the spare room into a nursery. Everything feels modern but the action is set four centuries from now. And yet the show is narrated by a group of musicians who appear to live in contemporary London. It’s a little confusing.

Ash and Emily are shocked to learn that a local factory has leaked toxic fluid into the Thames. And when Ash is personally implicated in the spillage he has to face Emily’s anger. The happy couple turn on each other and fill their little flat with screams of abuse. This is less depressing than it sounds. Despite the imminence of climate disaster, it seems that married couples will still be shouting at each other in 400 years’ time.

After Sunday is set in a drop-in centre where three overweight losers are learning to prepare Caribbean food. That’s how the show begins. Then a few oddities emerge. The cookery workshop is part of a hospital for the criminally insane where the apprentice chefs are detainees. The youngest of the trio recalls hitting a teenage boy with a bowling ball. Was it homicide? We aren’t told. An adorable old grouch named Leroy is hoping to move into a flat as soon as the authorities set him free. ‘Nice mix of people,’ he says of his new neighbours. Do they know he’s a murderer? That’s unclear too.

The convicts are learning to cook for their relatives on ‘Family Day’ but this highly theatrical event isn’t staged. And Leroy never experiences an emotional reunion with his estranged daughter. He just talks about it endlessly. Chit-chat is pointless. Dramatic engagement matters because it changes people. The author, Sophia Griffin, is a veteran of the Bush’s Emerging Writers’ Group but she has yet to learn what drama is. Perhaps the Bush is keeping it a secret.

Comments