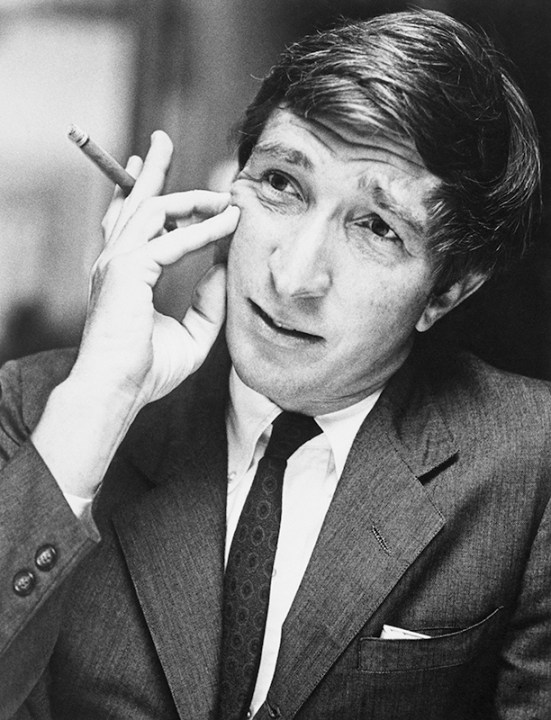

When John Updike died in 2009, aged 76, he left behind the last great paper trail. Novelist, short story writer, poet, essayist and art critic, he published with unstoppable fluidity in every genre. The sheer tonnage of his 60-odd books has now been augmented by A Life in Letters, a comparatively small sampling of the 25,000 or so epistles he sent out over the course of his life. This unwieldy volume serves up about 700 of them. I say he wrote with unstoppable fluidity (it was David Foster Wallace who dangled the question ‘Has the son of a bitch ever had one unpublished thought?’), but I should add that the letters and postcards (Updike loved a postcard) contain more than just pretty phrases. He talked shop – the writing, reading and manufacture of books – but also engaged in brave and sometimes anguished explorations of ambition, lust, love, guilt and shame.

‘Affairs are cruel, and if they are sin, they carry the punishment with them’

In his introduction, the editor James Schiff, a lifelong Updike scholar, whisks us past the landmark of a literary career. When Johnny was 11, an aunt gave him a subscription to the New Yorker. Two years later, he started sending submissions to magazines – the first glint of a keen literary ambition that never dulled. Aged 18, he escaped Nowheresville, Pennsylvania for college, choosing Harvard over Cornell (which offered him a more generous scholarship) because he rightly thought that the Harvard Lampoon, an undergraduate humour magazine, might launch him.

Launch him where? To his beloved New Yorker. He told its editor William Shawn that the magazine ‘formed the centre of my literary life and my life in general’. At 19, already hyper-attuned to the New Yorker vibe, he detected a new mid-century seriousness: ‘A magazine that once thumbed its nose seems to have shifted its hand and sadly scratches an ear.’ How many teenagers could so cleverly yoke two clichés?

Before the New Yorker (where Updike would eventually publish more than 750 short stories, poems, articles and reviews) there was his mother, Linda Grace Hoyer, an aspiring writer who taught him to aspire. A formidable woman, she recognised her son’s talent early and urged him to take flight, even as she hugged him close. He in turn loved her and did his best to distance himself unobtrusively, tiptoeing away but responding affectionately to the barrage of letters she sent him. Their correspondence, grounded in daily doings, is remarkable – but, sadly, Schiff gives only very little of what she wrote. She is a powerful absence.

Updike graduated near the top of his class at Harvard, where he wooed Mary Pennington, a Radcliffe student two years older than him with a wide smile and calm eyes. The love letters he sent her are as charming as any I know. Separated over the Easter holidays, he saw himself as a ‘ramshackle, yellow-fingered, hay-haired boy’, typing nervously on yellow paper ‘in the hopes that the postal service can bring him one foot closer to the distant Mary Pennington’. Three months later, having come ‘face to face with the reality of us, and the real goodness of us, and the grandeur of our love working for both of us’, he writes with a characteristic mix of self-deprecation and horniness:

I am very interested in sex; I love your body. There is no earthly reason why there is any conflict between this desire and the urge to write mildly obscure poems and vaguely bittersweet stories. I want to write well and achieve some degree of fame; I want to hold you in darkness, destroy you in passion, watch you as you comb your hair, remove your dress, butter your toast, read a book, paint a picture.

Reader, she married him – while he was still an undergraduate. The mother of his four children, all born before he’d turned 30, Mary was also for him, as he later confessed, ‘a kind of mother-substitute’ – gentler and less mercurial than his real mother.

In 1957, after 18 months in Manhattan, their second child now crowding the apartment, John and Mary decamped to Ipswich, Massachusetts, a coastal town some 30 miles north of Boston, where he thrived in every possible way. As he wrote in his memoir, they found themselves a ‘swim’ of young married couples: ‘There was a surge of belonging.’ In a nod to Mary McCarthy’s novel, they took to calling themselves ‘the Group’. It was a remarkably cohesive gang for nearly two decades – and suddenly it wasn’t.

An absurdly tangled web of love affairs brought a handful of marriages crashing down and shattered the Group. Anyone at all familiar with Updike will have assumed he was engaged in serial adultery. Here’s proof, in high definition. ‘I wish you were black with soot,’ he wrote to one married lover, ‘and I could lick you clean.’ He was grateful, he told her, ‘for your goodness, your shyness, your eyes, your tongue, your glimpsey ass, your yummy cunt’. He’d used ‘glimpsey’ before, in Rabbit Run (1962), and may have borrowed it from D.H. Lawrence, but it’s perfect here.

As for the word my wife would prefer I never use, especially in print, Updike chose it as the title of a long poem he published in a little magazine in 1973. ‘Cunts’ begins: ‘The Venus de Milo didn’t have one.’ The word appears in letters to his lovers (most often to Martha Bernhard, who became his second wife) and also in ones to the novelists Bernard Malamud and Erica Jong. He never used it in relation to his first wife, who memorably remarked that reading Couples (1968), his racy bestseller about the Group’s antics, made her feel ‘smothered in pubic hair’.

Mary didn’t want a divorce. She proposed instead an open marriage. John dithered. He wrote to her:

All these soft hopeful submissions of yours in bed seemed the very sum of love and I can’t imagine what else I want or why life, at least as lived by yours truly, has such a strong undercurrent of desperation and desire.

He cheated on his wife and also on his lovers. ‘Affairs are cruel,’ he wrote to one, ‘and if they are sin, they carry the punishment with them.’ His punishment – setting aside the serious and lasting damage to his relationship with his children – was banishment from Ipswich and the reckoning that accompanies expulsion from paradise. How, for example, to account for the jealousy of a man as promiscuously unfaithful as Updike? To Martha he wrote: ‘It needs sorting out, in my own deep sexual insecurity.’

The blow of expulsion was cushioned by plush literary triumph. By 1974 he was a celebrated author, rich and famous, king of the hill, where he remained – the gracious recipient of prize after prize, his face twice decorating the cover of Time magazine.

Four years before his death from lung cancer, he complained to Joyce Carol Oates (in a letter Schiff omits) of suffering from ‘word-disgust’. In a similarly downbeat frame of mind, he wrote to Ian McEwan the same year:

You have risen to be generally called the best novelist of your generation, whereas I have fallen to the status of an elderly duffer whose tales of suburban American sex are hopelessly yawn-worthy period pieces.

Like most writers, he fretted about posterity.

Yet the last book he wrote is one of his best. Published three months after his death, Endpoint is a slim volume of poetry, a half-dozen of the poems written when he knew he was dying. Seventeen of them eventually appeared in the New Yorker – which was, as he wrote in a late letter, ‘where I began and ended’.

Comments