The medics we knew and loved as ‘junior doctors’ were redesignated ‘resident doctors’ as part of their last pay settlement in September. If this was intended to boost their (already considerable) ‘self-esteem’, however, it seems not to have produced any maturing of their professional attitude.

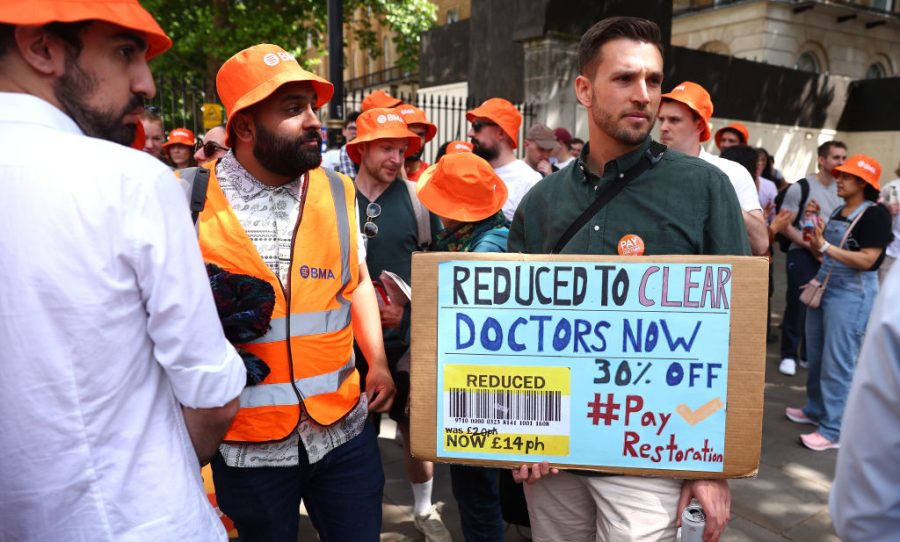

Less than a year after ending their last strike, they are balloting on striking again, in pursuit of a pay rise of 29 per cent (repeat, 29 per cent, no decimal point) to add to the 22 per cent they wrung out of the newly-elected Labour government. In a questionable attempt to increase the franchise, the British Medical Association (BMA) launched a free three-month membership offer halfway through the six-week voting period. Perhaps the union – sorry, professional association – fears the appetite for another strike has cooled. We shall see after voting closes on 7 July.

Permanent exclusion from NHS work, would be a serious deterrent to remaining on strik

If they do vote to strike again, however, what then? Another summer and autumn punctuated by cancelled appointments and delayed operations, and the NHS just about getting by. Or, is it not rather time for the government to say enough is enough?

Pay us, or else, they threaten. The ‘or else’, for the resident doctors, means emigration to Australia or Canada for salaries twice, or even three times, as high as in the UK, shorter working hours and an enviable lifestyles. Except that the number who actually leave, as opposed to those who threaten to do so, has remained pretty consistent over the years. If departures are what they are afraid of, it is time for the government – any government – to call time on this blackmail.

Let those who want to go, go – if they can find a job, that is – but on one condition: they pay back all their loans, including the large subsidy medics receive. The destination country may agree to pay, which is fine – they are probably still getting well-trained doctors on the cheap (just as we are when we recruit from poorer countries). The money recouped could fund more training places (and the closed-shop BMA should be compelled to abandon any resistance to increasing student numbers).

None of this, though, is likely to deter resident doctors from resorting to the strike weapon. Indeed, it could make them even more militant in pursuit of their own, rather than the patients’, interests. Which is why something more drastic could be needed.

Memories have faded, especially on this side of the Atlantic, but the government could do worse than take a leaf from the playbook of Ronald Reagan and the US air traffic controllers. After members of the Professional Air Traffic Control Organisation (PATCO) went on strike in pursuit of their claim for shorter hours and higher pay, Reagan invoked a then rarely enforced legal provision and summarily sacked the more than 11,000 PATCO members who refused an order to return to work. They were additionally banned from federal government employment for life.

I can already hear the shock horror from ministers at the very thought of such draconian action. It is true there is no law banning strikes in the public sector – except for the police, prisoner officers and the armed forces. What is more, the law on providing a ‘minimum service’ during strikes, based on the Continental European model, is set to be repealed when the government passes its Employment Rights Bill. But there is surely an argument that such a measure should be the very least required of a vital, monopoly public service such as the NHS.

Even without such a provision, though, the government is not without cards to play. It just seems pathetically reluctant to use them or to consider the interests of the patients on a par with those of NHS staff.

First, how much would the NHS have to fear from the mass dismissal of striking resident doctors? Patients managed without them during the last set of strikes, which the strikers deliberately complicated by refusing to give hospital departments advance notice of who was on strike on a particular day and who was coming in. At least this time there would be clarity.

Second, by no means all doctors belong to the BMA. And of those who do, by no means all would refuse a firm call to return to work, backed by the threat of dismissal. Resident doctors need to work to complete their qualifications and gain seniority and pay. An interruption, still less permanent exclusion from NHS work, would be a serious deterrent to remaining on strike.

Then there is the pay element. Resident doctoring is not just adequately paid, especially after the last generous rise, but constitutes a necessary bridge to far higher pay levels, job security, lavish extra pay from freelancing in private practice and pensions that most outside the public sector can only dream of. The sticks held by the government must include a clause saying that doctors refusing to provide a minimum service will be dismissed for endangering public health and patients’ safety and banned from NHS work for life.

That should whittle down the number of determined strikers. Then there is the large proportion of doctors recruited from abroad. Last year, 44 per cent of doctors newly registered with the NHS came from another country. Not all will be ‘resident doctors’, but many will be, because it is at the stage after initial qualification that many choose to move. NHS doctors’ work visas should include a signed commitment not to strike. No such commitment, no job, no visa.

This combination of serious sanctions, to include dismissal, could dramatically weaken the potency of the strike weapon in the health service – which indeed it should. It should also be remembered that even during the last strikes, without any of these disincentives or penalties, the NHS still managed to limp on. The low productivity endemic in the health service might even have been a positive factor here, as high levels of absence and inactivity are built into the system, even in normal times.

During the last strikes, at least some of the gaps were filled by consultants – a pleasant surprise for outpatients who found themselves seeing the actual doctor named on their appointment letter. If the consultants are also out of sorts next time around, however, their help may not be forthcoming, which is why the government and the NHS must set about changing the power balance with the resident doctors as a priority.

In dismissing the air traffic controllers, Reagan took a risk: that enough highly-trained professionals would give up striking rather than give up their job. He saw, too, that the US had enough slack – at a last resort, the military – to operate an emergency service if needed, while increasing opportunities for new entrants to train. Early-career doctors should not be allowed to hold to ransom a service that determines the life chances and well-being of most citizens.

The government has to finally challenge expensively trained doctors to take what the country can afford or find something else to do. And good luck with getting a better-paid, more secure, more lavishly pensioned opportunity with a vocational bent and high social prestige. Australia is a long way away, and its own health service has only so many jobs.

Comments