Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have gone into bunker mode. The pair – whose political fortunes are so tightly bound – have been forced all week to defend the Chancellor’s claims at last week’s Budget that there is a black hole in the country’s finances. Mendacity soon gave way to something closer to bewilderment. Neither can grasp why they are being called out for their omissions and dishonest briefings – always more fiction than fiscal – about the state of the economy. Their new argument is this: once you factor in the Budget’s own measures – welfare increases, the U-turn on winter fuel payments and the desire to increase headroom – a hole did indeed appear. They insist they had no choice.

What both fail to understand, however, is that voters can see these were choices. The black hole to be ‘filled’ was one created not by economic necessity, but by the Prime Minister’s political weathervane spinning out of control.

We are living through a historic transfer – fiscal and human – from work to welfare

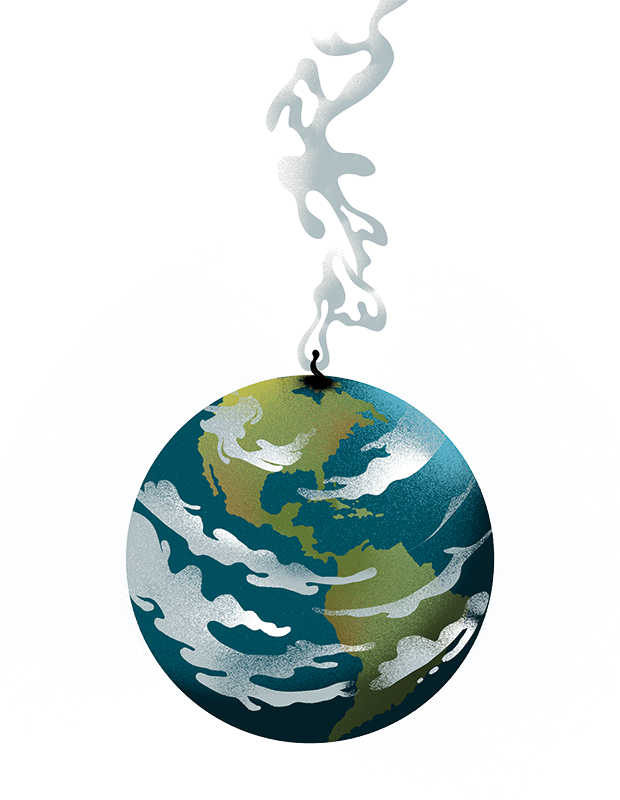

Peel back the politics and the story of this Budget is not headroom, inflation or growth. It is welfare. After last year’s Autumn Statement, the Office for Budget Responsibility forecast that by the end of the decade, nearly £1 in every £10 the government spends would go on working-age benefits. Labour’s second Budget has just added another £16 billion to that bill. Throw pensions into the mix and welfare spending is on course to hit £406 billion by 2030 – £109 billion of which will go on sickness payments.

To fund this, Reeves is euphemistically ‘asking’ those in work to pay more, pushing taxes to an all-time high and creating a system where the average person on £38,000 now hands over £2,000 a year simply to finance welfare. The squeeze is only going to get worse: someone working full-time on the minimum wage paid 12 per cent of their income to the taxman last year; by the end of the decade that will have passed 15 per cent.

We are living through a historic transfer – fiscal and human – from work to welfare. Labour has chosen a bonanza for benefit claimants funded by austerity for workers. And that transfer is accelerating. The most recent figures suggest that 6.5 million Britons are on out-of-work benefits, with more than five million under no obligation to seek work. The number of payrolled jobs has fallen by around 180,000 in a year. One in eight 16- to 24-year-olds – nearly a million young people – are now Neets: not in education, employment or training.

It is, in reality, spreadsheet socialism from a spreadsheet government. If the numbers balance out, the problem, it is believed, can be ignored. Welfare spending as a share of GDP is ‘no higher than in 2012’. So on paper it all looks fine – nothing to see here.

But believing this means wilfully ignoring a growing reality. Let’s examine the claim that total welfare spending as a share of GDP has been flat for decades. Welfare used to be dominated by unemployment; now the fastest growth is in sickness and disability benefits. When unemployment was 8 per cent, compared with about 5 per cent today, more people were at least looking for work. The chart being waved around in Whitehall does not capture the economic burden of a surging long-term sickness caseload – let alone the human cost.

Sam Miley, head of forecasting at the independent Centre for Economic and Business Research, says the rising incapacity caseload has cost an extra £14 billion in payments compared with pre pandemic, plus £13 billion in ‘forgone activity’ as people drop out of work altogether. The government’s own review by Sir Charlie Mayfield found that someone leaving the workforce in their twenties loses over £1 million in lifetime earnings – and the state incurs a similar cost. With around 5,000 people awarded sickness benefits every day, most of them unlikely to return to work, that is billions added to future tax bills. All this is entirely missed by that comforting spreadsheet which shows that welfare is ‘flat’.

Moving cash from the tax-producing parts of the economy to the benefit-claiming ones doesn’t just create a fiscal problem; it kills incentives. The question ‘Why should I bother with work?’ is becoming harder to answer.

Scrapping the two-child cap makes this worse. Analysis from the Centre for Social Justice shows that a family with one adult working full-time and the other part-time on the minimum wage takes home around £28,000 a year after tax. By contrast, a family with three children and no adults in work can expect upwards of £46,000 once Universal Credit, health benefits and Personal Independence Payments (Pip) are added. To match that standard of living through work alone, a family would need combined salaries of about £71,000. In theory, the household benefit cap should limit this. In practice, claiming a ‘qualifying’ benefit such as Pip means the cap vanishes; total benefit income shoots up. The incentive is obvious.

MPs comfort themselves that because fewer than 1 per cent of benefit claims are deemed fraudulent, the remaining 99 per cent must be genuine. But you don’t need to spend long on social media to see this is just not true. In one TikTok video, a man on UC because of ‘anxiety of interview’ explains how hard it is to live on his and his partner’s monthly budget of £2,272. Their ‘necessities’ include a Sky TV subscription, the upkeep of an African grey parrot and a monthly tanning session. Much of this content may be ‘rage bait’ – Oxford University Press’s word of the year – but newspaper investigations have found a plethora of disturbing examples. ‘Two-child cap scrapped, mate. Watch this space. Baby number three. Thank you, taxpayers,’ declares one sickfluencer.

It wasn’t meant to be this way. Throughout its history, when Labour has been out of office it has argued that decent pay and decent work were the only means by which working people could advance themselves. But when the party has been handed power, it has repeatedly deferred to spreadsheet socialism, with worklessness as the cost.

When Tony Blair won a 179-seat majority, he quickly worked out that there was an easier option than tackling welfare dependency in benefits Britain: mass migration. Job vacancies could be filled with cheap imported labour, while the proceeds of a growing economy could be used to pay benefits rather than reform them. Why pick a fight with campaigners chaining themselves to railings when you can import workers and let tax receipts do the heavy lifting?

Every government since has relied on the same economic cheat code, with young Britons paying the price. Last year, under-25 employment fell by 2 per cent, while non-EU under-25 employment increased by 16 per cent. But the trick no longer works. Today’s migrants are less skilled than those from the accession-era EU, and the OBR no longer confidently asserts that immigration automatically produces growth. Time to fix welfare, then?

The question ‘Why should I bother with work?’ is becoming harder to answer

Apparently not. Far easier to pin hopes elsewhere. Where Blair used migration to cover up the problems, Starmer and Reeves seem to have discovered a new saviour: artificial intelligence. The OBR said explicitly that not a single measure announced by Reeves would boost growth – but it did sketch an ‘upside scenario’ in which a successful AI rollout could lift productivity growth to 1.5 per cent a year by the end of the parliament. That would, conveniently, give Reeves enough fiscal space to reverse her tax rises, and fend off the uncomfortable question of who pays for the welfare surge.

But the point is obvious: just as one economic boom allowed Blair to ignore worklessness, another might let Starmer ignore it too. This isn’t a plan. It’s a hope that someone else – migrants then, machines now – will pick up the bill. Meanwhile the human tragedy continues.

The reality is that once-great industrial – and solidly Labour – towns and cities are languishing on welfare. More than one in five working-age adults in Manchester, Glasgow, Liverpool, Birmingham and Blackpool are on out-of-work benefits. Zoom in further and the picture is worse: parts of Grimsby, central Blackpool and Glasgow have more than half of all working-age residents claiming out-of-work benefits. Undoing that damage will be a huge, near impossible, task.

Far from lifting the working class through the power of work, Labour now seems content to let the work capability assessment become a trapdoor through which people fall into a lifetime of economic apartheid and structural abandonment. The generational pauperisation of our cities seems acceptable as long as the sums still add up.

If we are to solve this problem we must look beyond Whitehall and Westminster. Something changed in the national psyche during lockdown. Not showing up for work, skipping school, signing off sick – behaviours once frowned upon – became normal.

And it is not just ministers who must fix it. GPs have become far too ready to dish out sick notes – at a rate of 30,000 a day – rather than explain the medical benefits of work. ‘We don’t feel able to challenge patients if they want a sick note,’ says one. ‘They’ll complain. It’s very subjective.’ But with one poll finding that 83 per cent of doctors think antidepressants are over-prescribed, and that 84 per cent believe we have medicalised the normal ups and downs of life, it’s little wonder that mental health has become the main driver of rising sickness benefit caseloads and costs. This is despite the fact that studies show being out of work increases the risk of mental illness by 64 per cent, while those in work are 48 per cent less likely to have depression. This institutionalised kindness has turned out cruel.

Perhaps, though, attitudes are beginning to change. The National Centre for Social Research finds that a majority of Brits now believe the welfare system stops people from supporting themselves, while polling by More in Common shows that seven in ten think we should cut benefits for those who are able but unwilling to work.

If Labour fails to take heed of that trend, others stand ready to exploit the fairness gap it creates. Reform UK is ‘feeling confident’, as one senior source puts it, that internal polling shows the party can gain ground by tackling welfare dependency head-on. ‘We’re going to announce larger cuts than any other party, and not just on foreign nationals,’ the source says.

Labour was founded on the belief that fair wages and honest work was the path to dignity and that worklessness represented a failing Britain. Its modern-day custodians still make that case – but their actions suggest that, really, they see it as a challenge too difficult to overcome.

Comments