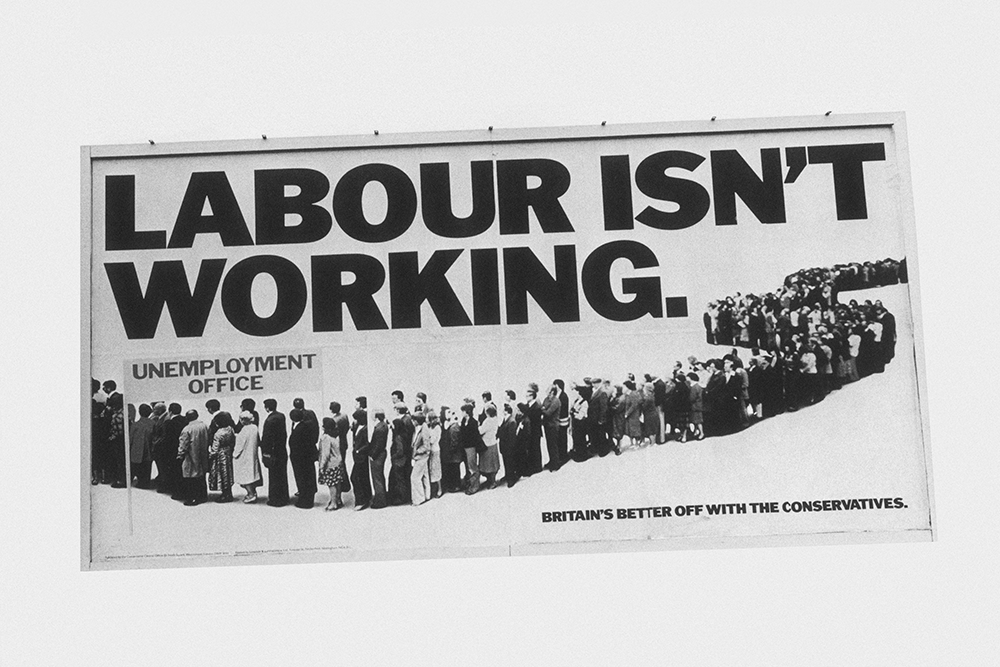

Labour: the clue should be in the name. In March, Keir Starmer branded Labour the ‘party of work’. If ‘you want to work’, he declared, ‘the government should support you, not stop you’. Even as his premiership staggers from crisis to crisis, that mission remains. If Labour doesn’t stand for ‘working people’ – however nebulously defined – it stands for nothing. As such, this week’s unemployment figures are more than just embarrassing for Starmer; they are a betrayal of his party’s founding purpose.

Unemployment has risen to 5 per cent – its highest rate since February 2021, in the middle of the third lockdown. There has been a 180,000 reduction in the number of payrolled staff since October last year – or rather, since Rachel Reeves’s first Budget increased employer national insurance contributions by £25 billion. The link between the two is undeniable. When Labour came to power, unemployment was at the low level of 4.2 per cent; it has remained largely steady in comparable economies such as France and Germany.

Labour have only themselves to blame. Ministers have made life as difficult as possible for employers. Not only has Reeves hiked NICs, she has increased the minimum wage to 61 per cent of the median. Simultaneously, the Employment Rights Bill threatens to introduce protection from ‘unfair dismissal’ from day one of employment, alongside guaranteed sick pay and contracted hours. While Labour backbenchers may cheer, even sympathetic thinktanks, including the Resolution Foundation and Tony Blair Institute, have been wary. Unlike the government, they seem to realise a simple truth: if you make it more costly and litigious to hire, employers are less likely to do so. As Ronald Reagan put it: ‘If you want more of something, subsidise it; if you want less of something, tax it.’

Alongside the NICs hike has been Labour’s failure to reckon with the perverse incentives created by Britain’s welfare system. Someone on incapacity benefits with personal independence payments (PIP) can expect to earn £2,500 a year more than a worker on the minimum wage. The number of benefit claimants with no requirement to look for work has risen by more than a million since Labour won the general election, passing four million, almost doubling in two years.

The unwillingness of Starmer’s MPs to swallow a paltry £5 billion in welfare cuts means the overall sickness and benefits bill will pass £100 billion by 2030 – even before the mooted unwinding of the two-child benefit cap and compensation for the so-called Waspi women, at a total cost of £14 billion. With both, there is an unmistakable sense of a government lurching to the left to buy off its supporters. But paying the Danegeld won’t get rid of the Dane. If Starmer and Reeves don’t hold the line on spending, more self-defeating tax rises will be required. The announcement that the Timms Review into PIP will not seek further savings should kill any hopes that Labour may reduce the welfare bill.

Before the Budget, Labour have seemingly done all they can to weaken confidence and halt hiring

But doing so is not only a fiscal imperative; it is a moral one. Pat McFadden, the Work and Pensions Secretary, has talked of the ‘crisis of opportunity’ of the unemployed, dispatching Alan Milburn, the former health secretary, to examine why almost a million 16- to 24-year-olds are not in education, employment or training (Neets). His particular emphasis will be on the link between mental health conditions and surging sickness benefit numbers: the share of claimants citing mental health issues has now hit 80 per cent. Many will have genuine problems, but the human potential wasted through sickness paying better than work compounds the fury of the dwindling tax base expected to prop up their dependency.

Britain’s employment market also faces several structural hurdles. Persistently high energy costs have not only wrecked our industrial base but sped up the switch towards a service economy in which men struggle compared with women.

The rise of Neets is a common problem across the western world, with a burgeoning cohort of graduates unable to find employment. This will be compounded by AI. Its cheerleaders promise a take-off comparable with the Industrial Revolution. But that will only mean a new cohort of Luddites losing out to disruption.

Starmer should aim to realise his March pledge: to make it as easy as possible for those who want to work to do so, to support businesses in creating jobs and to challenge the dependency cycle. Yet before the Budget, Labour have seemingly done all they can to weaken confidence and halt hiring. Potential tax rises and speculation about Starmer’s future have been paraded across the front pages. A manifesto-breaking income tax hike combined with a putsch against a Prime Minister who won a landslide only 16 months ago hardly suggests that Britain is the model of stability that ministers once heralded.

Yet even if MPs removed Starmer, the same challenges would remain. Until a government tackles the dependency trap, revives growth and escapes its fiscal death dance, any No. 10 occupant will be stifled. Expect the Conservatives to dust down their ‘Labour isn’t working’ posters from the late 1970s, as Starmer’s Britain comes to resemble that benighted decade ever more closely: political inertia, economic dysfunction and all-pervading gloom. Even with Labour’s poor employment record, this government is proving to be very hard work.

Comments