Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), diminutive aristocrat and radical artist, was roundly travestied in John Huston’s 1952 film Moulin Rouge, and at once entered the popular imagination as an atrociously romanticised figure doomed for early death.

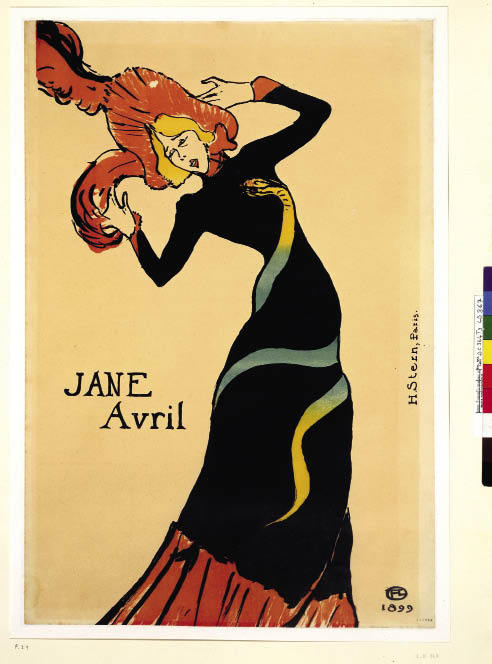

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), diminutive aristocrat and radical artist, was roundly travestied in John Huston’s 1952 film Moulin Rouge, and at once entered the popular imagination as an atrociously romanticised figure doomed for early death. In fact, Lautrec was a tough and original artist, incisive and unsparing in his observation though also compassionate of the human comedy, a perfect painter of what then passed for modern life. His images of the extraordinary dancer Jane Avril summon up Montmartre in the 1890s, but this exhibition aims to go beyond that evocative and enjoyable designation. It examines the close friendship between artist and model, but most particularly it explores the background of the dancer, and the context in which she became such an admirable subject. There is much new research here, and the art historical seriousness of the project is undoubtedly the main reason that museums have been so willing to lend works. (Indeed, MoMa New York has lent its only Lautrec to the show.) The result is a wide-ranging display which reacquaints us with the originality of the artist while opening up the period in which he worked.

The exhibition extends over two rooms at the top of the Courtauld, with an additional display of lithographs by Lautrec in Room 12 entitled ‘Stars of the Stage’ and dealing with other famous faces of the day such as Yvette Guilbert and Sarah Bernhardt. The main room contains a dozen or so images of startling potency, the agility of the paint-handling perfectly matching the captured movement of a series of instants. As Robert Hughes has presciently noted, ‘If the stream of life is divided into an infinity of fleeting moments, as it is by a culture based on photography, each looks like an actor’s gesture, a pose — or a snapshot.’ This is the effect of these paintings: impressive instantaneity, marvels of concision and economy, driven by piercing observation and a sure understanding of pictorial design.

Lautrec was a great poster designer, able to see through the endless possibilities and permutations of pose to the characteristic gesture (just this side of caricature) that defined personality. The use of thin paint made his paintings at times more like drawings, as the first image in the exhibition demonstrates. Here is Jane Avril, dancing on one leg, the other held high and kicking out, her clothes flowing and swirling through the expertly varied application of gouache. She was described by contemporaries as the ‘tempestuous tulip’ or an ‘orchid in a frenzy’, and as ‘combining the motions of a jig and an eel’. By all accounts, her lanky, rapid movements and trance-like mien were disturbing and fascinating, and although she was considered an eccentric rather than a classic beauty, there was a strong undertow of sexuality to her performance which made it compelling.

A substantial part of this exhibition is devoted to Jane’s story, and the discovery that she actually suffered from St Vitus’ dance. Indeed she was admitted to the Salpêtrière hospital for nervous diseases, where Professor Charcot preached the virtues of hypnotism and Sigmund Freud was a student, when she was 14. It was there she discovered that dancing helped her condition, even if it didn’t cure it. Fate seemed to take a hand, and she became a dancer by profession. One of her many nicknames was ‘La Mélinite’, after an explosive, a sobriquet she disliked perhaps because it reminded her of the Salpêtrière, which had once been an arsenal. Nancy Ireson, the exhibition’s curator, notes, ‘To read between the lines of Avril’s memoirs is to suspect that “difference”, though an element of her fame, was something of a burden.’

One commentator observed that Jane ‘wrote’ with her legs in a language that Lautrec understood, and the depth of this understanding can be judged from the depictions of her in this splendid exhibition. The oil- on-cardboard sketches of her seen from behind or dancing are crisp and scintillating and offer quite a contrast to her at the end of the night, leaving the Moulin Rouge, white-faced with exhaustion, meditative and almost demure. Or the vision of her arriving at the Moulin, subdued, withholding her light (saving it for the performance), looking much older than her 24 years. One of the highpoints of the show is the Art Institute of Chicago’s painting ‘At the Moulin Rouge’ (c.1892–5). Drenched in absinthe-coloured light, a group of bohemian friends gathers in conversation. At the centre is a blazing coif of auburn hair, Jane’s presumably, seen from behind. Front right is the greenish-white mask-like face of another dancer, May Milton. It’s a nightmarish scene, all too memorable. This is a small, intense, brilliantly focused exhibition: a pleasure to behold.

Sickert was not a great admirer of Lautrec, but the show currently at the Fine Art Society makes an interesting contrast to the Courtauld’s. A hundred years ago, the Camden Town Group formed around Sickert and held its first exhibition at the Carfax Gallery. The curator of this centenary celebration, Robert Upstone (who was also responsible for the Tate’s Camden Town show in 2008), defines their style as ‘vernacular and sympathetic, taking subjects from everyday life and human experience whether beautiful or banal with which we can still empathise today’. There is something of the immediacy of response in Camden Town that we find in Lautrec, but not so often the ultra-modern paint-handling. That said, this exhibition has a great deal to recommend it.

There are some 70 pictures in the gracious galleries of the Fine Art Society, representing most of the original names of the Group, and a good selection of their followers. If Wyndham Lewis and Augustus John, from among the founder members, are not here, there’s a strong representation of the unfairly neglected William Ratcliffe (I particularly liked ‘Hampstead Ponds’ and ‘Hill with Passing Train’), and some excellent discoveries (for me) such as Wendela Boreel’s ‘Piccadilly’ (1922) and Sylvia Gilman’s ‘Portrait of a Woman’ (c.1916). There’s a particularly fine selection of Sickerts, ranging from a Camden Town murder and a Dieppe church to a bright city square painting of Clarence Gardens. There’s also a vast tempera on canvas of the interior of the New Bedford Music Hall, commissioned by Ethel Sands for her dining room, and a superb drawing of two women watching a passing funeral out of a window in Mornington Crescent. There are also good things by Gore, Drummond and Bevan. An exhibition to linger over.

Comments