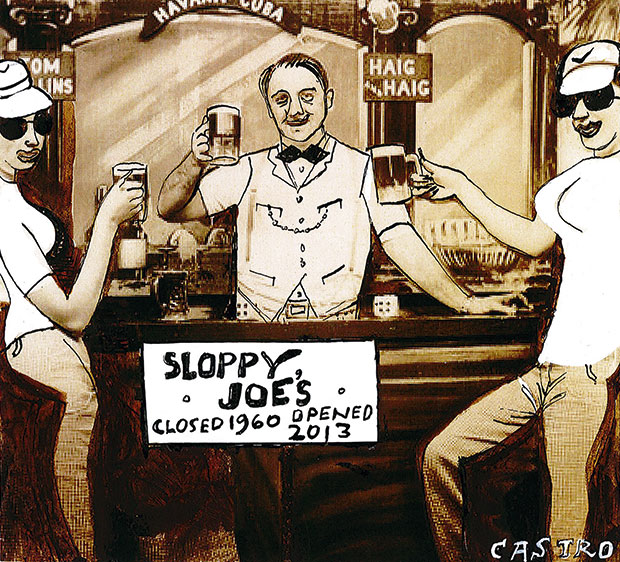

Sloppy Joe’s — which starred in the film of Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana — was always likely to wither on the post-revolution vine. As the decadent hangout of unsavoury ‘imperialists’ whom Fidel Castro despised, it never stood much of a chance. Frank Sinatra, John Wayne and local hero Ernest Hemingway all used to call in from time to time, slaking their thirst at the 65ft-long mahogany bar. It closed in 1960 and no one expected to see mojitos and daiquiris being poured here again, at least not until Fidel and his brother Raúl were gone. But needs must. Double measures and double standards keep Cuba alive. Two years ago, after government money paid for its restoration (the bar is still just as long, and just as shiny), it opened for business once more, playing on the past for all its worth while providing a goodish indicator of where Cuba is heading in the future.

‘Go to Cuba now’ is what everyone is saying following President Obama’s announcement that, after more than half a century, it’s time to lift sanctions. It will all be McDonald’s and Walmarts soon. I’m not so sure. Cubans may long for access to the internet (less than 5 per cent can get online at present); they yearn for a free press and dream of ending rations; but they have little appetite for Big Macs and all the capitalist trimmings. What’s more, Raúl has announced that he wants Miguel Díaz-Canel, the 54-year-old vice president, to take over when he stands down in 2018. Díaz-Canel is known as a hardline party apparatchik (although he liked the Beatles in his youth). He will have the support of the Cuban army when he’s in charge, still the most powerful institution in the country. Any ‘updating’, as the communist government delicately puts it, will be ‘within the limits of socialism’. Hold those fries.

My cousin, Andrew Palmer, was British ambassador to Cuba in the mid-1980s. At the time, the joke doing the rounds was: ‘Which is the largest nation in the world?’ Answer: ‘Cuba — because it has its government in Moscow, its army in Africa and its people in Florida.’ On Andrew’s watch, Gorbachev began to twitch the rug that eventually was pulled from under Cuba, and by 1991 the country was cut adrift, leading to the so-called Special Period when the Chryslers and Buicks ran out of gas and the Castros ran out of options, before Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez and his oil wells came to the rescue. Andrew is something of an ornithologist, a photographer and a good writer. His book A Diplomat and His Birds is a joy. But in the chapter on Cuba he doesn’t mention how the revolution failed on three fronts: breakfast, lunch and dinner. Today, the food is still as dreary as the crumbling architecture is exhilarating. With a dollop or two of irony, some of the best food in Havana is served at Mama Ines, where Fidel’s former chef wears the whites (although when I was there three weeks ago he was sporting a polo shirt with ‘New York’ on the front). He must have a story or two to tell about his former boss, but perhaps not as juicy as those flowing from the pen of Juan Reinaldo Sanchez, Castro’s bodyguard from 1977 to 1994. He says Fidel is worth more than £100 million and that doesn’t count his many properties, including one in Havana with a bowling alley on the roof. I like the story about Fidel having his own cow to provide him with a constant supply of milk because at the age of 88 he is still paranoid about being poisoned.

The arts scene in Havana is suitably subversive. In his swish studio on the outskirts of town, Esterio Segura showed me his latest creations, including a wall of painted plates. Segura has painted 50 or more plates, one for each of the years Fidel was president and a few more to represent him still being alive but not at centre stage of life in Cuba. For each of these he has depicted Castro having sex with women, in all kinds of different sexual positions. On the last few plates there is no sign of Castro — just a woman playing with herself with the barrel of a gun. I asked Segura if he ever feared a knock on the door. ‘No,’ he said. ‘One thing about Fidel is that he has a sense of humour.’

I called in to see the current British ambassador, Tim Cole. He told me that Raúl is busy playing down expectations following Obama’s announcement on 17 December and that short-term detentions for speaking out of turn were down in January but up in February. Fluent in Spanish, Cole is enjoying Havana. On Monday evenings, he invites fellow ambassadors round for salsa lessons. There’s no shortage of takers. His expected return to London next year will be dull by comparison.

Comments