Several people I spoke to when this exhibition was first mentioned thought it would be a Hockney retrospective, considering that he was commandeering all the first-floor galleries at the RA. But actually the retrospective element is very slight, consisting of half a dozen early landscapes and a couple of photo-collages, before we encounter the first of the mainly large-scale landscapes he has been painting since the late 1990s. In fact, the greater part of the exhibition (sponsored by BNP Paribas) consists of work done in Yorkshire since 2004, and Hockney has packed the galleries with hundreds of images (a single work might consist of 36 watercolours, or perhaps 51 iPad drawings with an oil painting on 32 canvases). The sheer energy and productivity on view cannot be anything else but impressive. Unfortunately, almost none of this recent work possesses a fraction of the intensity of the early landscapes, such as ‘Ordinary Picture’ (1964) and ‘Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians’ (1965). What we have here, in gallery after gallery, is brash, loudspeaker art, shouting all the fun of the fair but delivering precious little.

From the moment the visitor enters the exhibition, to find the Central Hall hung with four large paintings of eight canvases each, depicting the same group of three trees near Thixendale, as seen through the seasons of 2007–8, the designation of Hockney as our Greatest Living Painter seems utterly ludicrous. With the death of Freud last year, pundits and commentators have been racking their ill-equipped brains to think of a suitable successor, and Hockney (always much in the public eye, with his predilection for the limelight) has seemed the obvious choice. But, as this exhibition abundantly demonstrates, he is not a great painter. He is not even a natural painter, for his greatest skills have always been as a draughtsman. If there must be the title of Greatest Living Painter, then award it to someone who actually uses paint in an inventive and interesting way: to Leon Kossoff, Gillian Ayres or Frank Auerbach. The publicity-hungry Mr Hockney does not deserve it.

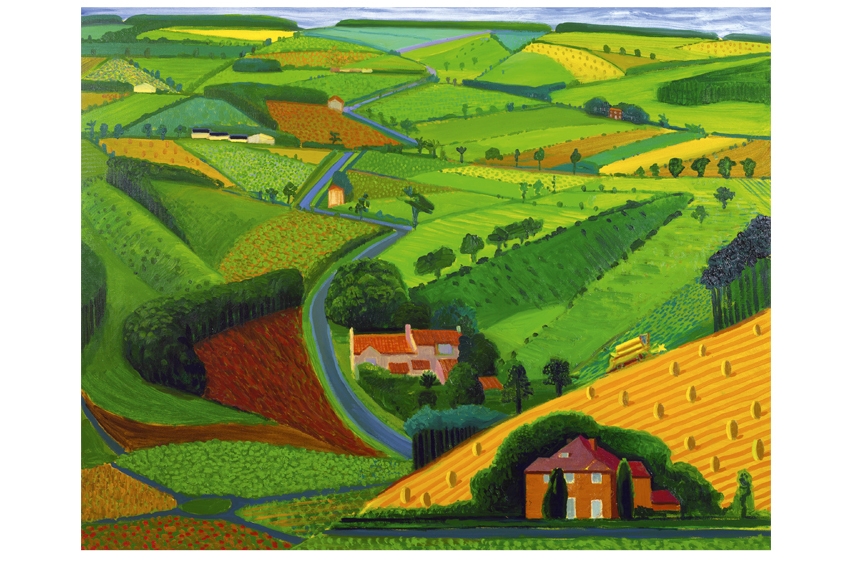

Those paintings in the Central Hall are crudely brushed, crudely coloured and crudely composed. To spread each image over eight canvases only exaggerates its deficiencies, it does not make them bolder or stronger or more convincing. It seems extraordinary that Hockney should have fallen so blatantly for the misleading maxim that bigger is better. Yet this is the philosophy of the whole exhibition, as the title attests. How marvellous it would have been to see Hockney condense these images into one canvas of modest proportions, and make something really potent and telling of his subject. But nothing is further from his intentions than modesty, and as a consequence we are confronted with this display of overblown and empty rhetoric — ostensibly on the subject of the English landscape.

Yet there is no understanding of the subtleties of the English countryside in Hockney’s work. He claims to have made many of these pictures from direct observation, and yet for an artist so technically interested in ways of seeing, his own paintings provide little enough evidence of real looking. The oils seem to be more about what Hockney expects to see than what he has sensitively observed. The most truthful aspects of this overgrown exhibition are the drawings and watercolours. With these, there is no attempt to be grandiose, no temptation to allow gadgetry to interfere, no mediation between artist and thing looked at. With the paintings, something gets in the way, and when it’s not some new gizmo, I can only think it is Hockney’s own ambition. He is certainly obsessed with technological advances, and is apparently convinced that nine movie cameras must be better than one. Therefore eight canvases must be better than one. It’s logical, isn’t it?

But painting doesn’t work like that, and Hockney’s pictures simply don’t merit the scale on which he paints them. Again and again it felt as if one had wandered into a storehouse of stage sets and scenery painting, or vast billboard travel posters. Room 9, the main gallery, is given over to a gruesome array of blown-up iPad drawings, a mixture of wriggling lines and soft-focus candy-colour, which resembles nothing so much as a sample room of schmaltzy greetings cards. At best, these are demonstrations of the versatility of the iPad, not art but computer graphics. The enormous, floor-to-ceiling iPad prints of Yosemite have a greater impact, perhaps simply because of their size. And I was quite surprised to find myself liking some of the most recent paintings, on the way out, all-over patterns of woodland growth at tree-foot. But that was perhaps because one couldn’t get far enough back to see them properly.

I had high hopes of the paintings of hawthorn blossom, from one or two images I had seen in reproduction, but this room is just as bad as the others — if not worse. Sprays of blossom are made to look like sausage-shaped iced buns or limp baguettes. Tentacular boughs make vaguely obscene gestures, as hectic patterns suggest nightmare swarms of munching caterpillars. The best things in this room — as so often — are the charcoal drawings, but even these bear very little relation to the reality of hawthorn bushes. It’s hard to believe that Hockney has spent any time looking at the countryside, for all his much-vaunted claims. And yet the best room by far is the small one devoted to his sketchbooks. It reminds us — if we needed reminding — that this fellow can draw all right, which only serves to make the rest of his output all the more disappointing.

Megalomania is the real message of this exhibition. Here is an artist with indisputable delusions of grandeur. One moment Hockney decides that no one has painted en plein air in England for the past 50 years (blatantly ignoring a whole crowd of distinguished and very talented artists), and that he is going to change all that; the next, that ordinary film and photography are inadequate and he’s going to record his rural subject matter with nine cameras simultaneously. Or why not 18? One of the RA galleries is given over to the 18-screen gimmick: mildly vertiginous when applied to landscape, rather more effective when filming dance. But the result is no closer to the way we actually see than any other kind of film or photography, whatever Hockney might claim.

I’m rather horrified by the chorus of approval that has greeted Hockney’s latest efforts, but then society applauds the art that reflects it best. This is art for the channel-surfer, for those with limited attention spans who don’t know how to look at paintings, nor want to. This is art for people who think they have no time, who walk past pictures and do not stand and stare. Pause to examine Hockney’s new landscapes and their weakness — of conception and execution — becomes immediately apparent. Take a single canvas out of its nest of crudities and it simply won’t bear scrutiny. This could never be said of his imaginative and highly original early work, which I have long admired. The trouble with Mr Hockney now is that he is overrated, overindulged and over here. Couldn’t he go back to Los Angeles? He seems to understand it there.

Comments