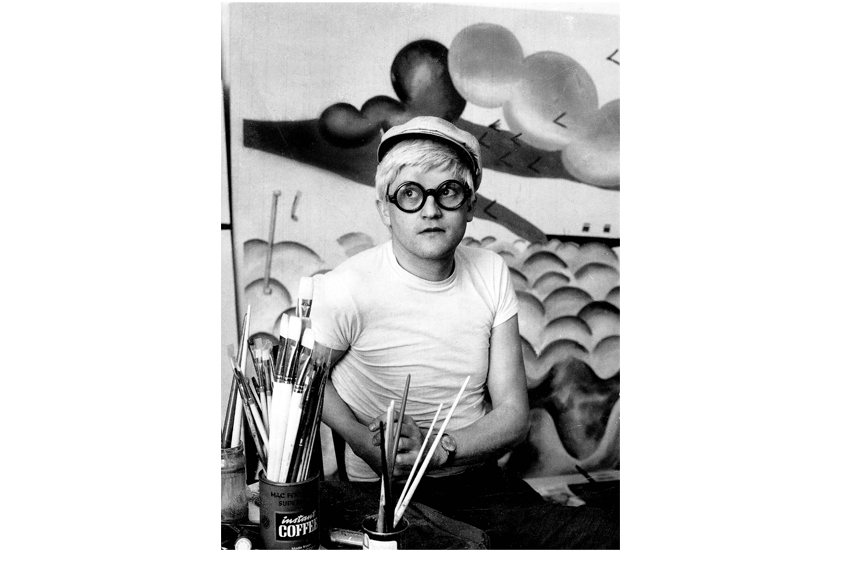

Seduced by the hayseed hair and the Yorkshire accent it’s tempting to see the young David Hockney as the Freddie Flintoff of the painting world: lovable, simple, brilliant, undoubtedly a hero, and delightfully free of angst. In this enjoyable book, which sets out to to ‘conjure up the man he is and in doing so to put his paintings and drawings in the context of his extraordinary life’, Christopher Simon Sykes provides us, naturally, with a more complex story. Hockney is a hero if course — not least to homosexuals, for blazing a stylish and courageous trail to emancipation in the 1960s, and more recently to beleaguered smokers in his stand against politically correct bullying. And he shares with Flintoff that irresistible suggestion of innocence combined with strength — like a figure out of one of the fairytales that Hockney so memorably illustrated.

Sykes conjures up the settings in which the young artist’s originality, his prodigious appetite for work, friendship and life in general, was played out: Bradford in the Fifties (where heraldry was still on the art- school syllabus), and the sleezy and glamorous circles in London, California, and Paris between which Hockney divided his time in the Sixties.

We see Hockney the conscientious objector and militant vegetarian (his first serious paintings inspired by vegetarianism), Aldermarston-marcher and Cliff Richard fan, who modelled his appearance, for a time, on Stanley Spencer; we see him taking the waters at Vichy and delighting in promiscuous sex in LA; breakfasting alone at the Café de Flore as he takes refuge in Paris from a broken heart; staying with the film-director Tony Richardson at Le Nid de Duc; taken by John Pope-Hennessy, the Director of the V&A, to visit Harold Acton at La Pietra.

We have Hockney the clown, the rebel and the Boy Scout; the music-lover, the patient friend, the thoughtful and devoted son. And inside the ‘gregarious Yorshireman’ and enjoyer of life whose energy sustained a whole raffish entourage of friends, admirers and hangers-on, we have the single-minded artist with the necessary ruthlessness to be able to get on with his work amidst all the distractions of adulation, sex and high living.

The account of David Hockney’s family and boyhood is particularly engaging, and Hockney père a character of Dickensian dimensions: a devout Methodist (Hockney’s parents met on ‘a Methodist ramble on the moors’), serious photographer, natty and ingenious dresser; conscientious objector whose stand caused his family to be persecuted by neighbours; passionate campaigner against hanging and smoking, founder-member of CND and poster-maker for his various causes.

Hockney’s own strength of purpose was demonstrated early: from the age of five, his sister Margaret remembers, ‘he seemed to know what to do in the world’. When he discovered at Bradford Grammar School, to which he had won a scholarship, that only the less academically gifted had proper art lessons, he simply stopped working and by this ‘tactical idleness’ was relegated to the bottom form.

There are already many excellent books about Hockney, including several by the always articulate painter himself; and at 75 he was reluctant to waste time on another, and was ‘in no mood for reflection’. But judging by his photo on the jacket, Sykes is clearly a genial and persuasive fellow, and Hockney eventually agreed to a biography which is ‘authorised’ but not ‘endorsed’.

This first volume, covering the same ground as the painter’s My Early Years (1976), up to the designs for The Rake’s Progress at Glyndbourne in 1975, more than justifies Sykes’s determination, and combines a serious account of Hockney’s upbringing and artistic development in a fluent narrative with a light touch and an obvious enjoyment of the many remarkable, exotic and sometimes disreputable characters, both celebrated and obscure, with which the story is richly populated.

Sykes has been allowed to quote freely from the diaries of Hockney’s mother, which give a fascinating and touching new angle, and he draws on the memories of Hockney’s large family, as well as on conversations with friends and lovers, and on his friendship with the artist himself.

The freemasonry of the gay community welcomed Hockney from the outset into exalted company, so that in addition we have the benefit of seeing him through the eyes of such noted diarists as Christopher Isherwood, Cecil Beaton, Keith Vaughan, Derek Jarman and countless memoirists, from whom Sykes quotes extensively.

A selection of key works, with attendant technical challenges and autobiographical ramifications is discussed in some detail and used to illustrate the progress of Hockney’s artistic career. These are collected as groups of colour plates, with black and white photographs and drawings (including some juvenilia) dispersed throughout the text.

Comments