In the weeks since the Labour government came to power, we’ve gone from debating compulsory teaching of maths until age 18 to entertaining the idea that the times tables may be too stressful for children to memorise.

My resilience, my determination and my empathy are largely products of being bad at maths

When I was at school in Poland in the 2000s and 2010s, the response to such a suggestion would have been an eye-roll, or the blowing of a loud raspberry. The comment that ‘if you can’t have what you like, then you must learn to like what you have’ was commonplace, and maths was taken by everyone until age 18.

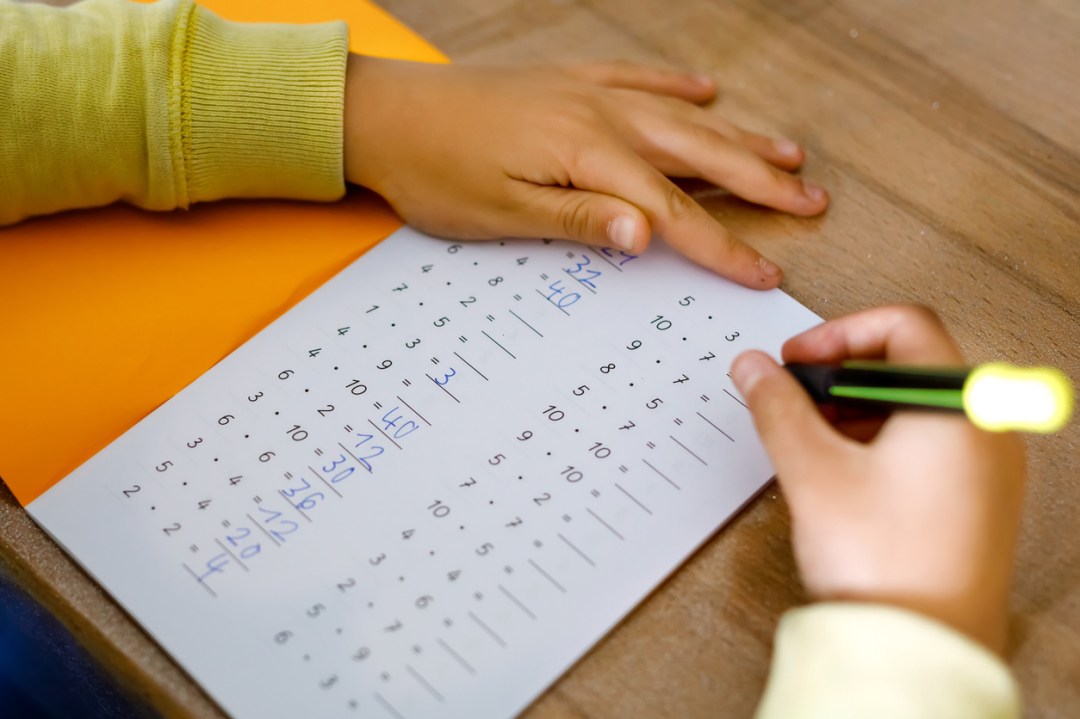

I was at the top of my class until, at age 15, I began to fall behind in maths. My school insisted on educating everyone as if they were a budding mathematician, so I ended up having to spend my evenings in remedial maths classes, stubbornly picking apart integrals and differentiation, calling my cousin – who was studying maths at university – for help, crossing out line after line of equations, and generally losing my mind. At school, the teacher took delight in calling me to the blackboard and pointing out to the entire class how unprepared I was.

Mathematics taught me that learning could be hard. It taught me to say ‘I don’t know, I need help with this’. It taught me how to swallow my pride, how to endure the embarrassment of continually asking for help until it was no longer embarrassing. It taught me compassion, that circumstances can be complex, that there are people who get left behind academically through no fault of their own. It showed me that there are teachers who are patient and kind, and will speed one along, and others who are harsh and inflexible, who will slow one down – and how to manage both.

It was in no way to the advantage of the economy to teach me maths – the economy gains more from me when I play to my strengths in the humanities, for example – but it was of considerable advantage to my development as a human being. My resilience, my determination and my empathy are largely products of being bad at maths. If children are never made to do things at which they do not excel, they will grow up under the false impression that they are bad at nothing. The longer this illusion lasts, the more painful it is when it’s inevitably shattered.

More authoritarian societies, such as China, will impose a challenging curriculum from above, telling their students to deal with it. Their children may be more anxious, but they will be more resilient and better equipped to deal with the real world. Meanwhile, British children slide further and further into a fantasy world which will diminish their ability to deal with reality, which is often unsympathetic to their anxieties. The truly ambitious ones will still choose to do hard things, as they always have – usually in fee-paying schools, in the case of Britain – while the rest fall behind and take the future of the nation with them.

It is possible that in an age where technology can count and calculate for us, the utility of teaching the times tables in schools is marginal. But as artificial intelligence advances, we are ever more under a duty to train and develop ourselves – not for our utility to the economy, which may one day very well run itself, but for our fulfilment as human beings, and to be useful to ourselves and other people.

Comments