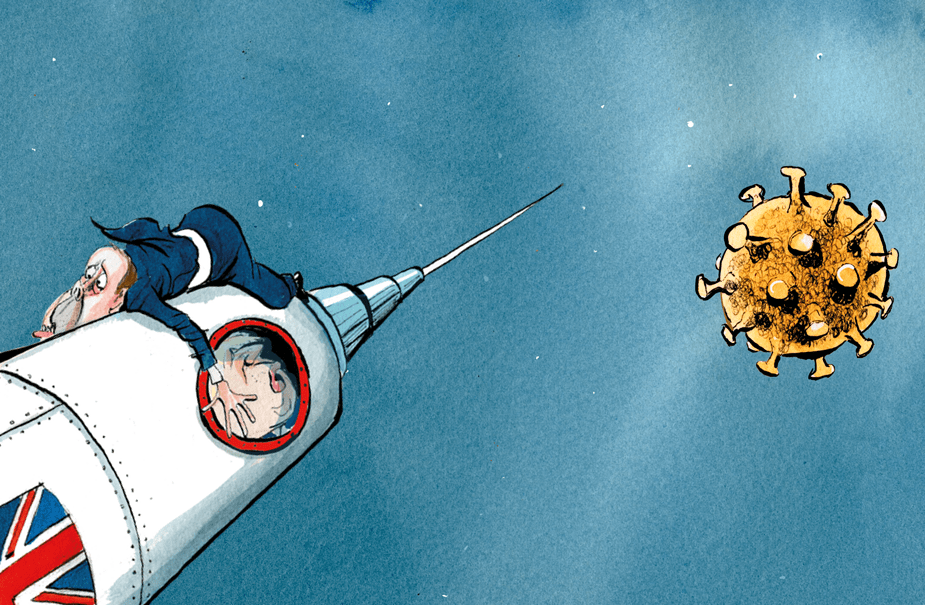

Ever since the Oxford-AstraZeneca team announced the results of its Phase 3 trials last November, there has been a suspicion among some that their vaccine is the poor relation of the messenger RNA vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna. It might be cheap compared with the others, it might be easy to store and transport, but the results published last November indicated that it had an efficacy of 70 per cent compared with over 90 per cent for Pfizer and Moderna. Even that was questioned when it was pointed out that the 70 per cent figure was arrived at by mixing different trials, involving different quantities of vaccine. When a half dose was followed by a full dose (a regime which occurred as a result of a mix up of doses) it seemed to have an efficacy rate of 90 per cent, yet when two full doses were given that dropped to 62 per cent.

You don’t have to be Emmanuel Macron — who claimed last week that the Oxford-AZ jab was ‘quasi-ineffective’ for the over-65s — to wonder whether it is an inferior vaccine to the others. Sweden joined Poland and Germany in deciding they will not administer it to the over-65s — and they have a point in claiming that there is a lack of data on use in that age group. Moreover, questions have been asked about the UK approach to vaccination, with the length of time between shots extended to up to 12 weeks in an attempt to get as many first doses administered in as short a time as possible.

On Tuesday, however, Oxford University put out a pre-print of a paper for the Lancet which appears to show that a single dose of the Oxford-AZ vaccine is more efficacious than the initial results suggested and seems to justify the government’s decision to delay the second jab. Indeed, it suggests that the vaccine is far more effective when the gap between jabs is at least 12 weeks.

The paper reports ongoing results from Phase 3 trials, which involved 8,948 individuals in Britain and 6,753 in Brazil. There is now much more data available: at the time of the last published results there had been 131 infections among the participants; now there have been 332. The new study takes the story up until 7 December.

Between 22 days and 90 days after a single standard dose, the vaccine was found to have an efficacy in preventing symptomatic infection of 76 per cent (although there is quite a wide 95 per cent confidence interval in this figure: from 59 per cent to 86 per cent). Efficacy did not appear to diminish over this period, and there was a minimal decline in the level of antibodies detected in the participants’ blood. A single dose was found to reduce all infections (including asymptomatic ones) by 67 per cent — which suggests that the vaccine is effective at preventing transmission of the virus.

The study found that after two doses, efficacy increased in line with the gap between those doses. When there were fewer than six weeks between doses efficacy was just 54.9 per cent. But when the two doses were given at or more than 12 weeks apart, efficacy rose to 82.4 per cent. The 54.9 per cent figure does raise the question: does a second dose actually damage the working of the vaccine if given too early? Or could some other factor be at play? Further research will be needed to answer that question.

No participants in the trial who were given the vaccine were hospitalised, while 15 in the control group suffered hospitalisation. Overall the results are likely to be taken by the government as justification for its current vaccination regime: giving two doses of the Oxford-AZ vaccine 12 weeks apart. What this study couldn’t tell us, of course, is whether a 12-week gap is equally appropriate for the Pfizer vaccine — for which the manufacturers recommend a three-week gap. Questions will also be raised about mixing the results from trials in the UK and Brazil, given that different variants have been found to be circulating in both countries. On the positive side, if Brazil were ravaged by a vaccine-resistant variant of the virus, it would presumably have shown up in this study.

Comments