Another outbreak of the Tory Modernising Wars! What larks! Nick Boles’s speech to Bright Blue, a newish think tank for metropolitan swells folk who think the Tory message needs rethinking, has, as it was designed to, caused a minor rumpus.

Rod Liddle thinks Boles is off his head. Iain Martin is kinder but concludes the Cameroons are still obsessed with fighting the wrong battles. Other commentators are gentler still, conceding that Boles is asking the right question but that he’s searching for answers in the wrong places. Nick Denys and, to some extent, Paul Goodman fall into this camp. On the other hand, Ian Birrell and Matt d’Ancona essentially agree with Boles while James Kirkup concludes that Boles has inadvertently conceded the failure of the Cameroon modernisation project.

Annoyingly, most of these verdicts have some merit. Unfortunately, the argument about modernising the Tory party has often been misunderstood. It is less a battle to replace the existing Conservative party with a new entity – whether called National Liberal or something else – but a means of broadening the Tory appeal. It is not an either/or proposition but rather, something messier and harder to define. It is a both/and discussion.

That is, Tories can be “strong” on law and order, defence, and europe but they also need to be more “in touch” with modern Britain. This is, to be sure, a difficult finesse to pull off. Nevertheless, at least the modernisers realised that it was, and remains, a real challenge. Their opponents sometimes seem to think the whole thing a foolish waste of time designed to appeal to a handful of celery-munchers in north London.

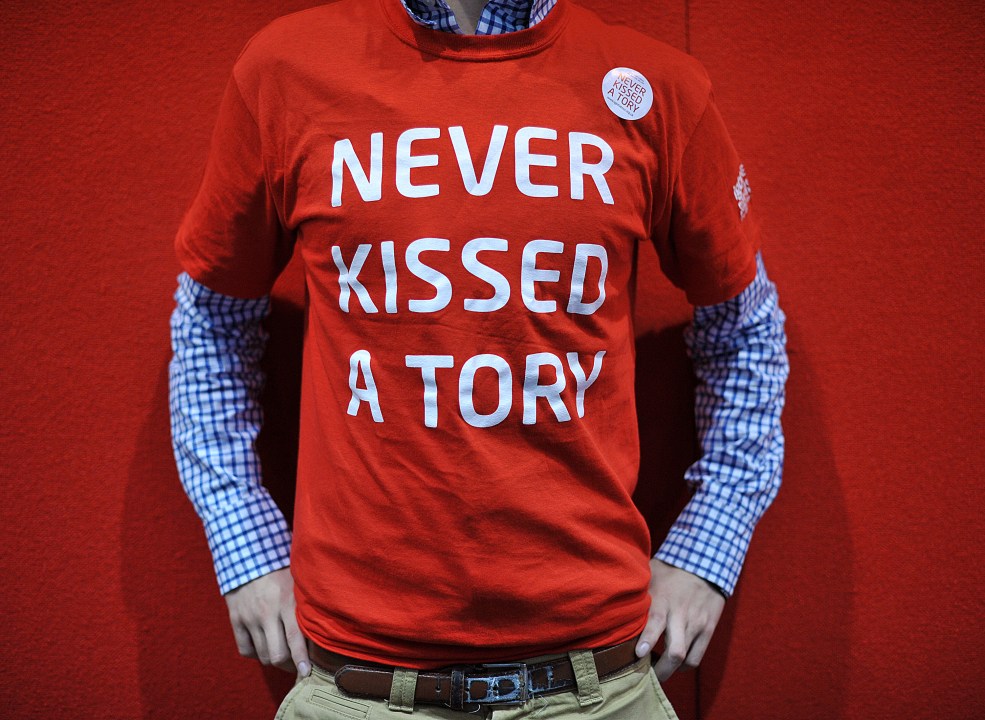

It is rather more than that. The Tory problem is really three large problems, the importance of which is increasing with every election. They fail to appeal to younger voters, they fail to appeal to non-white voters and, too often, they fail to appeal to voters outwith the south-east of England. That’s a hefty chunk of the electorate. It means the Tories must do better amongst older, white, voters at each succeeding election just to maintain their present strength. The core vote is not enough.

That may be sustainable for an election cycle or two but it is not a long-term proposition you’d want to bet on. It means that every five years the prospect of a Tory majority shrinks. It means that the centre of political gravity shifts a little to the left.

The old Jesuit boast,“Give me the child for seven years and I’ll give you the man”, applies to politics too. The young voter who votes Conservative now is much more likely to continue voting Conservative in the future. Political preferences change, of course, but previous votes remain a leading indicator of future votes.

And, of course, political preferences are also often inherited. Or, if not precisely inherited, then shaped by parental views and prejudices. It can be hard to be the first person in your family to vote Tory.

Conservatives, on both sides of the Atlantic, love harking back to the glory days of the Thatcher-Reagan era. And if is true, as Iain Martin says, that Reagan suggested the eleventh commandment should be “Thou shalt not speak ill of any fellow Republican”, a message the Tory modernisers, in their zeal to broaden the party’s appeal beyond its base, have perhaps too often forgotten. But it is also true that Reagan and Thatcher persuaded people to vote Republican and Tory who had never previously supported those parties. Where are David Cameron’s equivalent of the Reagan Democrats?

Of course the Tory platform must be broader than trumpeting the virtues of gay marriage and husky-hugging. No-one disputes that. But these are still important signals. Supporting gay marriage is the right – and the conservative – thing to do. It’s not just a sop to metropolitan liberals even if it is also, though this is of secondary importance, a useful way of demonstrating that the modern Tory party might surprise voters prepared to give it a look for the first time. It is about earning the right to be heard.

Impressions are delicate creatures, easily bruised. Sure David Cameron (and half the parliamentary Conservative party) might support gay marriage but what about the membership? Perhaps Reigate Tories are not typical of the tribe but the fact the local party association sought to deselect their MP because he has the effrontery to be a homosexual demonstrates the extent to which the party remains out of touch.

The fact a majority of Tory members supported Crispin Blunt’s reselection bid is something but it matters less that Blunt won this battle than that it had to be fought in the first place. It damages the Tory “brand” beyond Reigate; it tarnishes it everywhere. Because it says this is not a party for people like you.

The “you” in this instance is not gay Britons. It is much worse than that. The “you” is anyone who doesn’t give a hoot about anyone’s else’s sexuality.

The reason for changing with the times is to make it easier for voters to listen to you on the matters and problems that don’t change with the times. The Tory traditionalists seem not to understand this.

It is the same with race. Tories, like their Republican cousins in the United States, look at family-minded, culturally-conservative, entrepreneurial ethnic minority voters and wonder why these people are so unlikely to vote for right-of-centre parties. They should be natural conservatives!

And, of course, there is something to this. If these voters were white they might well be Tory or Republican supporters. But they don’t support these parties because they sense that, deep down, these parties are not for people like them. Worse than that, actually, they think these parties don’t like people like them and that these parties think the country would be much better off with fewer people like them.

No set of policies notionally tailored to meet these voters’ aspirations will ever be strong enough to overcome the instinctive lack of trust engendered by that suspicion. Identity and belonging matter. A party that talks about immigration in the wrong way is a party that will not win the votes of immigrants. Nor will it win the votes of their children and grandchildren. And, increasingly, it will struggle to win the votes of younger voters who don’t give a damn about skin colour or religion.

Other signals matter too. It is hard to imagine a surer way of reinforcing the prejudice that the Tory party is the party of the rich than by increasing VAT for all voters and cutting income tax for millionaires. Yet that is precisely what this Tory-led government has done.

The economics of cutting the top rate of tax are one thing; the politics of it quite another. It remains a colossal blunder that is not compensated for by increasing the tax-free allowance (not least because, inconveniently, that was a Liberal Democrat policy). It sends the message that the Tory party’s heart really lies with the wealthiest Britons and their interests.

This is unfortunate and, as it happens, also untrue. Nevertheless, the damage has been done and will not, again, be made-up for by schemes such as Help to Buy (a policy with many shortcomings but one at least targeted towards aspirational Britons). That too is too easily dismissed as a kind of make-up call.

It is, of course, also true that the Tory party needs its core vote. True that it is little good winning new supporters from the centre if this comes at a cost of losing “traditional” voters. Again, it is a question of balance and emphasis. As Boles suggests, a one-size-fits-all, one-identity-covers-all, approach is ill-suited to a fluid political landscape in which old allegiances are questioned and old certainties rendered irrelevant by the march of time. (Meanwhile, I note that those people most concerned with not alienating “core” voters are also often those happy to push for an alliance of sorts with UKIP regardless of the cost this might impose in terms of votes lost in the centre-ground.)

Boles, in fact, is really arguing for something else and trying to move on from the weary debate between modernisers and traditionalists. Nor is he advocating a retreat to a mushy, ill-defined centrism. On the contrary, he seems to me to be asking for a looser, more relaxed, form of conservatism that emphasises what conservatives have in common, not what divides them. And that means there must be a place – a warm place – in the party for Britons of all nationalities, identities and backgrounds. A bigger, better, tent.

Which means, in the end, that the problem with modernisation is that it has been too clumsy and too binary. Briton is a large and varied place which means, in the end, the Tory party must be too. None of its sections, not even the largest of them, are enough on their own.

Identifying that problem is one thing; solving it quite another but in the longer-term Boles gets more things right than he gets wrong.

Comments