The departure of the former Scottish First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, from active politics draws a line under the Scottish National Party’s greatest generation. Her former mentor, Alex Salmond, died suddenly of a heart attack in October. Now, Sturgeon has told her supporters that “the time is right for me to embrace different opportunities and to allow you to select a new standard-bearer”.

Sturgeon, of course, relinquished her hold on the standard of government in February 2023 when she resigned suddenly and plunged her party into chaos from which it has yet to recover. When she departed Bute House, in the wake of the scandal over her flagship Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill, the SNP was still leading the Scottish opinion polls, and her personal popularity remained high.

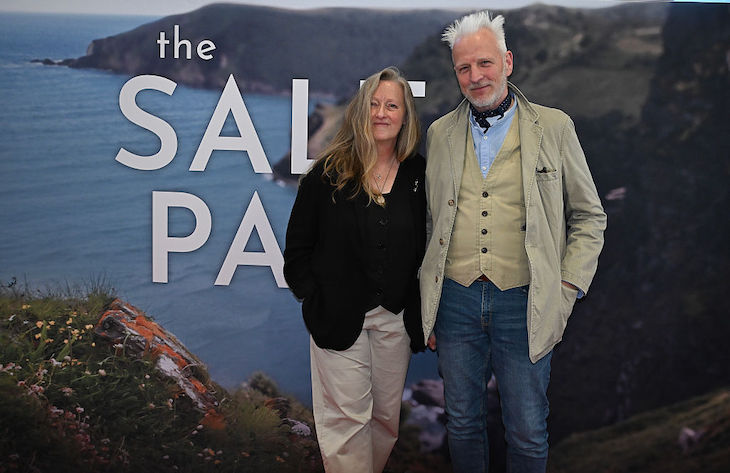

Sturgeon never succeeded in translating this electoral success into movement towards Scottish independence

Indeed, under her nine-year leadership, the SNP won landslides in successive general elections and was still by far the largest party in Holyrood and Westminster when she resigned. The pinnacle of her electoral achievement was the 2015 general election landslide, in which the SNP won 56 of Scotland’s 59 Westminster seats.

However, she never succeeded in translating this electoral success into movement towards Scottish independence. There was perennial frustration in the party membership over her failure to “move the dial” on a repeat referendum on independence, which she frequently proclaimed was imminent when it was not.

Before she resigned as First Minister, Sturgeon had dropped large hints for most of the previous year that she was tiring of the rough and tumble of Scottish politics and was looking for new challenges, possibly in the literary field. She has been a regular attendee of book festivals, is close to authors such as the Scottish crime writer, Val McDermid, and has, of course, written her own memoirs, which will be published in September.

Sturgeon leaves a party that has written off much of her legacy. First Minister John Swinney has abandoned attempts to lift the UK government’s block on the gender bill. Her coalition with the Scottish Green Party, under the Bute House Agreement of 2021, is long gone. And the Scottish government has ditched the ambitious emissions reduction targets she established. Only this week, it scrapped her plans to replace a million gas boilers by 2030.

Before the COP26 environmental gathering in Glasgow in 2021, Sturgeon announced a Climate Emergency. But most of the measures she introduced to address it have disappeared.

Climate aside, Sturgeon said she wanted to be judged on her ability to close the educational attainment gap. But Scottish education standards declined during her period in office and the poverty-related attainment gap remains as wide as ever.

Sturgeon is still under police investigation over the alleged misuse of campaign donations in Operation Branchform, and her husband, the former party chief executive, Peter Murrell, has been charged with embezzlement. She recently announced her separation from Murrell, to whom she has been married for 15 years. Murrell denies the charge.

It is not clear to what extent Operation Branchform has influenced her decision not to contest her Glasgow Southside seat at the next election. Her arrest and the police erecting a blue forensics tent outside her home must clearly have been traumatic. She has insisted throughout the three-year investigation into party funds that she has done “absolutely nothing wrong”.

However, the adverse publicity over Branchform may have prevented Sturgeon, who was widely respected abroad as a leading advocate of LGBT rights, from seeking the leading international human rights role that many believe she had hoped to secure after leaving politics. Sturgeon was damaged also by her split with Alex Salmond over allegations against him of sexual misconduct, which Salmond always denied. Even many nationalists who did not side with Salmond believed that Sturgeon handled the issue badly. The investigation into the Salmond allegations, which she authorised, was condemned by the Court of Session in January 2019 as “tainted with apparent bias” and Salmond was awarded £512,000 in costs. He was eventually cleared of all charges by the High Court in 2020.

The SNP will have mixed feelings now that Nicola Sturgeon has finally announced her departure from Holyrood. They will celebrate her many election victories. Her conduct of the daily Covid-19 press conferences was much praised, even by non-nationalists. But they must realise that her policies, especially on gender and the environment, led to a breach with many mainstream Scottish voters. The SNP lost 38 of those Westminster seats in the July election, and though Swinney has steadied the nationalist boat, hopes of an independent Scotland – at least in the next generation –will depart with their most successful leader.

Comments