Nicola Shulman begins her rehabilitation of Thomas Wyatt by remarking that there is ‘an almost universal consensus that he can’t write’ — a consensus established within a generation of his death in 1542.

Nicola Shulman begins her rehabilitation of Thomas Wyatt by remarking that there is ‘an almost universal consensus that he can’t write’ — a consensus established within a generation of his death in 1542. Even the Earl of Surrey, his friend and eulogist, acknowledged his verse to be ‘unparfited’, and by Shakespeare’s day he was a joke: Malvolio keeps a poem of Wyatt’s about him, proclaiming himself a nincompoop.

Like Malvolio, Wyatt excels at such un- attractive emotions as ‘grievance, reproach, disappointment and unrequited desire’, and his expression of them is obscure as well as clumsy. Shulman illustrates this by considering one of his most obscure lyrics (LXXVI, in R.A. Rebholz’s Penguin edition), which finds him in his ‘customary pose of resentful defeat’:

Such Hap as I am happed in

Hath never man of truth, I ween.

At me fortune list to begin

To shew that never hath been seen

A new kind of unhappiness…

‘Each successive verse,’ she writes, ‘promises an explanation that never comes, because we are sent, for clarification, back to something we already don’t understand, except as a pregnant indication of something unclear.’ What is this ‘Hap’ he is ‘happed in’? The hap referred to in LXXXVII — ‘But spite of thy hap, hap hath well happed’ — is clearly a fundamentally different hap, albeit equally obscure.

None of his poems was printed in his lifetime. Intended for the inner circle of Henry VIII’s courtiers, each began life on a folded piece of paper tucked into Wyatt’s doublet, was then ‘passed slyly to a friend … or left somewhere a girl would find it’, and then borrowed, circulated and copied. His audience lapped them up, because they knew what he was writing about, and at Henry’s secretive and paranoid court ‘poetry was the hot vehicle for gossip and rumour’.

None of his poems was dated, either, which often makes it impossible to identify with any certainty the relevant gossip and rumour. The solution, Shulman argues,

is not to try to ‘match’ each lyric to an occasion, but to play the story of Wyatt’s life behind them and see how often they change, as Wyatt would put it, their devise. And why.

This she does with spectacular brilliance.

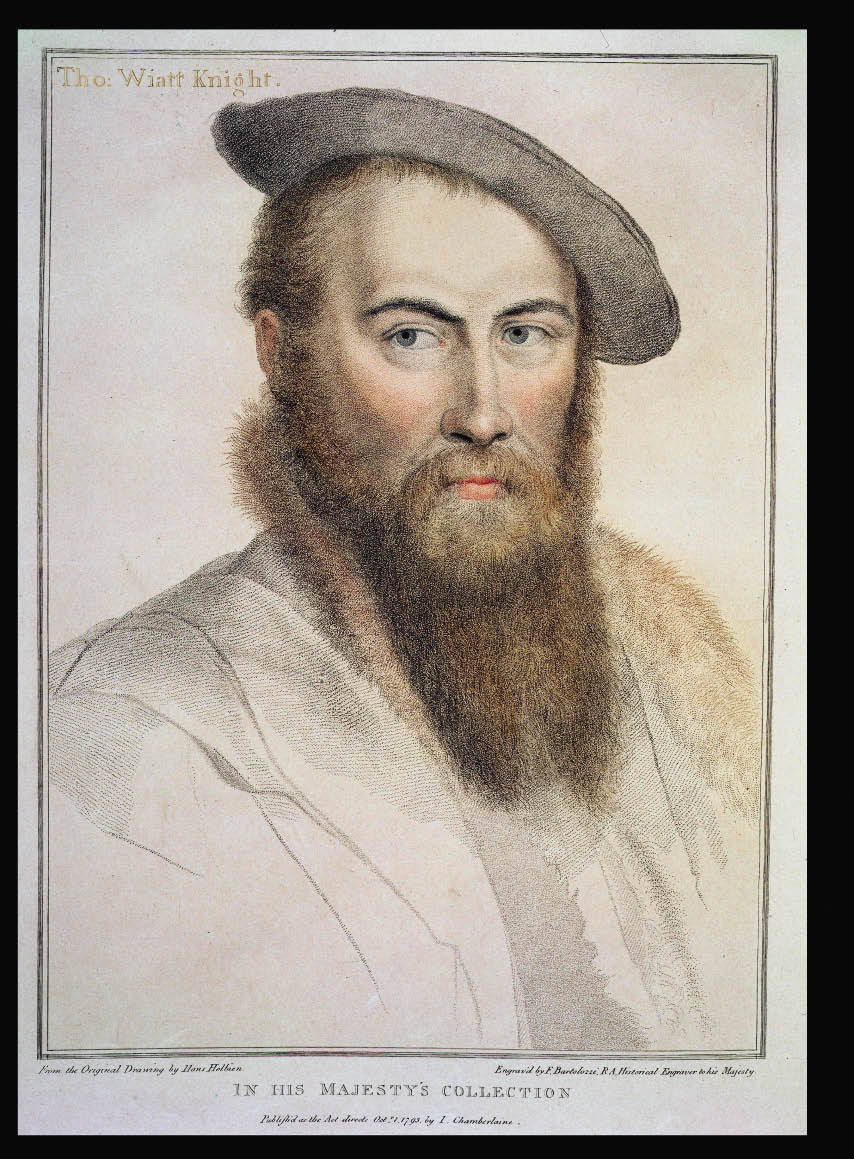

The first son of Sir Henry Wyatt, who prospered mightily under both Henry VII and his brother Henry VIII, Thomas Wyatt was born in 1503 at Allington Castle, Kent, and probably educated at St John’s College, Cambridge. He made good progress as a courtier, being appointed an esquire of the court in 1524, and in 1529 an esquire of the body, which meant that he shared the King’s lodgings, and was provided with five horses and two beds.

That September he left the court for Calais, where he remained for a year and became High Marshal — an honourable office, but also a form of exile. There has been endless and inconclusive speculation that he left England because he was conducting a dangerous affair with Anne Boleyn, whom the King loved, but was un- able to marry until 1532. Certainly some of his poems seem to be about her, notably XI, which supplies the title of Shulman’s book:

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere for Caesar’s I am

And wild for to hold though I seem tame.

Shulman argues that, since Wyatt’s ‘unstable’ lyrics abound in ‘double hinges and sliding panels’, these lines may well offer a coded reference to Boleyn’s role in the break with Rome, with the sense of, I am the new Church. Do not touch me, for I belong to the King.

When Anne was charged with adultery in 1536, Wyatt was among those arrested with her and confined to the Tower, where he was given handsome lodging, with ensuite privy, in the bell tower, from which he may have witnessed her execution:

The bell tower showed me such a sight

That in my head sticks day and night. (CXXIII)

He was released by the intercession of Thomas Cromwell, whom he served as ambassador and spy, but in 1541, the year after Cromwell’s execution, he was again in the Tower, in far worse hap than before, with powerful enemies intent on his death and without view or ensuite. This time he was saved by Catherine Howard, perhaps at the prompting of her cousin Surrey, but the next year he died of a fever, contracted by hard riding on a last errand for the King.

Deftly combining the skills of critic, biographer and historian, Shulman illuminates the poems by their context, and vice versa, and persuasively argues that, ‘If it is the business of art to express the conditions of its making, these [poems] are some of the greatest works of art ever made.’

Comments