The Islamist terrorist Ali Harbi Ali will spend the rest of his life behind bars for the murder of Sir David Amess MP. But as he fades from public view, will his risk also disappear? That’s a headache our beleaguered prison service will now have for decades to come.

The signs are not promising. Harbi Ali, who reportedly smirked after stabbing Amess more than 20 times, showed no sign of remorse or contrition throughout his trial. Unlike many of the terrorists he will be joining in one of our high security prisons, he managed to convert his distorted thoughts into lethal action. He’s a blooded jihadist and he will be an iconic figure to many within the system, not just those locked up for ideological crimes.

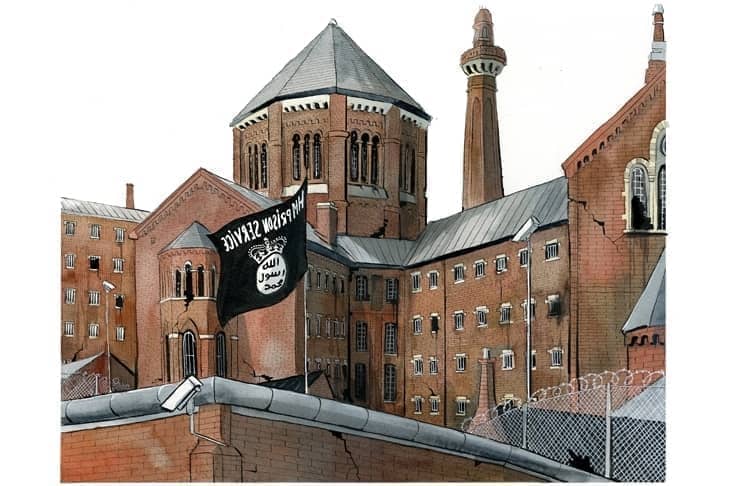

Ali Harbi, now a jihadist ‘rock star’ will enter a high security prison system which is continually struggling to contain active risk

This is not to say that he’s an inevitable risk. We simply don’t know enough about the 230 odd terrorist offenders in our prisons, who swim in a sea of 78,000 or so of our most impulsive, violent, vulnerable and immature citizens. Some of the earlier generation of Al Qaeda inspired terrorists claimed to be fighting against foreign policy. We haven’t seen them continue to be a problem after incarceration. But the later IS inspired attackers, motivated by the idea of a global caliphate, particularly those thwarted in their jihad, continue to pose a serious risk. Only last month, Ahmed Hassan, who nearly caused several deaths when the bomb he was carrying partially exploded on a tube train in 2017, was convicted of an attack on the unit manager of our allegedly most secure unit – HMP Belmarsh High Security Unit. The victim stated in court that he feared he was going to be killed, such was the ferocity of the assault.

So Ali Harbi, now a jihadist ‘rock star’ will enter a high security prison system which is continually struggling to contain active risk. I’ve written before that terrorism does not stop at the prison gate. But our criminal justice agencies have too often acted as if it has, encouraging a culture of impunity for toxic ideas and violent extremism to curdle and worsen without sanction. Jonathan Hall QC, the government’s independent reviewer of terror laws will likely underline this weakness when he publishes his forthcoming review of terrorism in prison.

Although pursuing people who glorify or enable terrorism behind bars is welcome, it is likely to make little difference to people like Ali Harbi or the few other terrorists who have been given similar whole life terms. The old lag’s aphorism applies in spades: ‘what are they going to do, send me to prison?’ Management of the risk of people who have nothing to lose, surrounded by available and poorly protected agents of the state, with all day and every day to observe patterns and exploit weaknesses is a fraught and complex challenge.

It’s inconceivable, given the judge’s sentencing remarks, that someone with the proven capability to kill in such an outrageous way, to attack democracy itself, won’t be designated at the start of his sentence as an exceptional risk category A prisoner – the pointy end of the risk spear. Ali Harbi has been on remand for some time, so he does not begin his sentence as an unknown quantity. He will have undergone a lengthy period of assessment and observation already. If he is determined to proselytise his violent jihad and call others to it, it will be essential he is removed from general circulation altogether and housed where he can’t preach hate in one of the separation centres that I recommended were created for this purpose in 2016. It has taken ministerial intervention and the removal of some of the policy control to the Home Office to finally force the prison and probation service to make proper use of those units. Wherever he goes, until he becomes physically or mentally incapable of advancing violent extremism he will remain a danger. Those managing his risk would do well to recall his startling evidence in court about just how easy it was to deceive authorities into leaving him alone simply by agreeing with them so he could further his murderous plans. Disguised compliance is an ever present threat.

Ali Harbi might alternatively be located in one of a number of Close Supervision Centres located in some of our high security prisons. As the name implies, these centres are for prisoners who represent a serious control problem and require extra precautions when being unlocked and supervised. The last high security prison with such a centre to be inspected in September last year, HMP Woodhill, was slated for poor security, very high levels of violence and chronic staff shortages with an inability to recruit and retain front line officers. Meanwhile, HM Prison and Probation Service grows like topsy with one part time chief executive, two directors general, a chief operating officer and 14 executive directors. Ministers might want to note the disparity. Suits won’t keep us safe. Boots will.

Wherever he goes, Ali Harbi Ali will bring notoriety and risk with potential danger to staff and prisoners. Despite the challenges, the men and women putting on a uniform will be there to look after him until he dies. Hidden from public sight behind the walls they are also prime targets. There is always the possibility of redemption although it’s difficult to imagine a way back from such a heinous crime. We can live in hope. But very, very carefully.

Comments