This book recounts a terrible story of self-destruction by two painters who, in their heyday, achieved considerable renown in Britain and abroad. Robert Colquhoun (1914-62) and Robert MacBryde (1913-66), both from Scottish working-class families, met in 1932 when they were students at the Glasgow School of Art. From then onwards they were personally and professionally inseparable in their headlong rise to fame and descent downhill. Although both have been the subject of anecdotes and snapshots in many a memoir of the period — all those accounts of Soho and ‘Fitzrovia’ — this is the first full-length study devoted to them, the result of over 20 years’ research.

Their early life is reasonably well documented and is even more so during their student years when both received a rigorous training in Glasgow, becoming outstanding draughtsmen. Their talent was quickly recognised and they received grants to travel in Europe.

The author gives a good account of this Grand Tour — the one-night cheap hotels and forbidding train journeys forming a background to their intoxicating aesthetic discoveries. In the war, Colquhoun suffered the usual indignities meted out to pacifists; MacBryde was exempted from service on health grounds.

They were eventually reunited in London and quickly met the right people — Peter Watson, the Maecenas of Horizon, the supportive Duncan Macdonald of the Lefevre gallery and, later, Wyndham Lewis, who commended them in his reviews (particularly when their work showed his influence) — as well as the roistering crowd of writers, painters and hangers-on invoked in Julian Maclaren-Ross’s famous Memoirs of the Forties. They knew George and Elizabeth Barker, Ruthven Todd, Lucian Freud, Dylan Thomas, John Craxton and the changing flotsam of Soho and Charlotte Street (but surely they must have encountered Nina Hamnett, Queen of wartime Bohemia, whose barstool at the French Pub eventually became her personal commode).

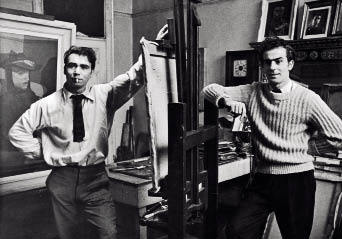

The two Roberts were soon launched. They were at first associated with the Neo-Romanticism of the period as seen in the work of Craxton, Graham Sutherland and their friend John Minton, but it was the Polish emigré painter Jankel Adler whose work made a decisive impression, not always for the good. The influence of Picasso was generally risky but, as filtered through Adler, it became risible. Once Colquhoun hit his stride however he was able to produce the ‘Woman with a Birdcage’ (Bradford) and ‘The Fortune Teller’ (Tate), among his best works; and MacBryde came through to a heraldic style in still life that is quite his own (am I alone in frequently preferring the latter’s work to Colquhoun’s often portentous figures, despite his stronger talent?). Both purveyed a bleak humane impulse that briefly caught the public’s imagination. The paintings sold well and the artists were photographed in Vogue and Picture Post and were heard on the BBC. They were a distinct and beguiling pair.

Colquhoun was taciturn, nerve-racked, roughly handsome with abundant celtic imaginings and a usually gentle manner. MacBryde was shorter and more rotund, sang and danced and recited and always carried something of the stage Scotsman about him; his nature was more outgoing and quick witted than Colquhoun’s. He was the provident housekeeper with a knack of domestic improvisation — stews were rustled from thin air (when he had finished painting a still life of the ingredients); he was famous for once ironing with a heated spoon. The two were obviously good company and there were parties and gatherings in their Bedford Gardens studio (shared for some time with Minton who developed a hopeless crush on Colquhoun).

It is difficult to pinpoint the reasons for their decline. The death of their dealer, Macdonald, in 1949 was a blow; the Neo-Romantic moment was passing and although neither of the Roberts was a paid-up member, their imagery of conspiratorial figures in rooms, twisting vegetation and bristling cats had strong enough affinities for the artists to be carried out of favour as the movement waned and their colleagues, such as Keith Vaughan, developed new directions.

But as becomes horribly obvious from this book, drink was at the heart of their downfall. There were pub-crawls and benders of epic proportion. The two men became intolerable company, uttering the same incomprehensible accusations and insults. No glass, bottle or piece of furniture was safe. Left together in their increasingly dismal rented rooms they rowed ferociously. By the early 1960s Colquhoun was emaciated and obviously ill, and while working on a drawing early one morning in 1962 died of a heart attack. MacBryde lingered for four more unproductive years and was killed by a car one night in Dublin as he tried to make his way home.

In spite of humorous and convivial moments, the story is depressing in the extreme. Admirable as they were in their independence and stoicism, their relatively early deaths were a waste of considerable gifts. But the story is hardly helped by Roger Bristow’s dogged writing. There’s not a sentence that catches fire. Social and political scene-settings are rended in the Artex prose of a wikipedia entry. There is too much repetition and some callow writing about art — Picasso’s Cubist paintings were not ‘experimentations’, for example.

On the other hand, the author has, over a long period, carried out a commendable amount of research and managed to speak to many artists and associates who have subsequently died, such as Jeffery Bernard, Prunella Clough and George Barker, all with their pennyworth of vivid reminiscence. The book takes rather a heavy fall between two stools — biography and monograph — and the narrative is too often interrupted by accounts of stylistic development or individual works.

Nevertheless, the entwined story of the protagonists is absorbing in its delineation of promise and achievement, disintegration and death. What is needed now is a sparely chosen double-retrospective to remind people how good the Roberts could be.

Comments